The chaotic anxiety of early Yeah Yeah Yeahs renders Fever to Tell more important now than ever

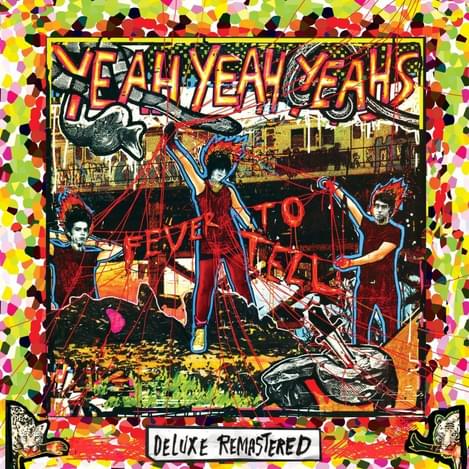

"Fever to Tell [Deluxe Remastered]"

2017 is not a significant anniversary year for Fever to Tell - not unless the number fourteen means more to Karen O, Nick Zinner and Brian Chase than we know. It’s not as if the New York City trio will imminently deliver new music, either; sure, it looks as if we might well be in receipt of LP5 at some point in 2018, but until then, the band’s individual members will continue with their individual extracurricular distractions, from O’s contributions to the new Parquet Courts/Daniele Luppi crossover to Zinner’s electronically-centered work with The Haxan Cloak.

The reasoning behind Fever to Tell’s return to prominence, then, is apparently nothing more complicated than its long-term absence on wax, a state of affairs egregiously unacceptable to genuine Yeah Yeah Yeahs devotees. It’s hard not to think, though, that perhaps Lizzy Goodman’s irresistible New York City rock and roll memoir Meet Me in the Bathroom had something to do with this; after all, it paints this particular three-piece in as thrilling a ramshackle light as anybody else it brings up, whilst - almost uniquely - not calling into question the personal decency of the individual players.

O is now the consummate rock icon of that particular age, her stage presentation landing pretty flush between Siouxsie Sioux and Lux Interior. She only became involved in playing music because the university she was attending - Ohio’s revered Oberlin College - insisted upon students taking up creative term distractions during the winter term, not least because the bleakness of the season was known to foster an especially savage suicide rate.

She is the liberal arts student referred to in the title of a chapter of Goodman’s book as ‘a girl who sings quiet folk songs’. Zinner, meanwhile, always seemed like a visual artist first and an indie rocker second, and has a well-documented and deep-seated fascination with what westerners might term ‘world music’. Chase was the only one who had his heart set upon playing rock and roll in New York in advance of the advent of Yeah Yeah Yeahs.

That such an unlikely hat-trick of people would come together to produce an LP that was every bit as zeitgeist-defining as Is This It or Turn on the Bright Lights was as thrilling as it was improbable. Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Machine, the two EPs that the group put out ahead of their first album proper, fizzed with the same feral energy that, say, PJ Harvey’s 4-Track Demos did, and yet, just as was the case in the early nineties, you didn’t feel like you heard those songs properly until the genuine article came along. Fever to Tell was to provocative noughties indie rock what Rid of Me was to the same niche a decade earlier; a chaotic symphony in sex, debauchery and bottomless anxiety.

Herein lay the difference between Yeah Yeah Yeahs and so many of their contemporaries. There was no posturing on Fever to Tell; no attempt to look cool for the sake of it, no effort to cleave to any given set of aesthetic ideals and, most crucially, no concern as to how right-on or otherwise their political expression might be construed. “Rich” opens the record with that towering electronic loop, and only hints at so much of the rest of the record’s sweat-drenched havoc.

No wonder then, thereafter, that they wanted to let loose as explosively as they did with the perma-ticking punk time-bomb that was “Date with the Night”. It shouldn’t have been shocking that the album’s poppier moments - the melodically-conceived “Pin” among them - would, too, become scrappy rock throwdowns. The epic crackle of “Y-Control”s monolithic synths, meanwhile, served as further evidence that this was a band with a fondness for spectacle.

Quite aside from that, though, Fever to Tell was only ever going to be looked back on as perhaps the crucial work of the early noughties NYC scene in terms of its occasionally searing stance on gender politics. There’s the casual, but dramatic, inversion of the usual tropes on “Black Tongue” - “boy, you’re just a stupid bitch, and girl, you’re just a no-good dick”. O is on vicious form on the anti-love song “Man”, and then, within twenty minutes, is utterly bereft on “No No No”, a song that’s less about heartbreak than the Dementor’s-Kiss emotional aftermath of it.

Much of O’s appeal was tied up in exactly that - her ability to present as impenetrable punk queen one minute and as emotionally destitute the next, as she was so memorably on “Maps”, with Chase’s unforgettable drum turn underscoring the rolling drama. This side of O was reinforced, too, by the handsome lethargy of defeatist closer “Modern Romance”. The untrained eye would peg Fever to Tell as a record of two halves, one that swells with incendiary rock contrarianism on the one hand and wilts prettily under the sort of emotional pressure rampant in millennials on the other.

It’s so much more than that, though; it’s an album that’s perhaps the ultimate ambassador for the historic scene from which it emerged and yet, still, its emotional intelligence and nuanced sexual politics will be the aspects that truly stand the test of time. The scheduling of this remaster might be peculiarly timed, but it allows the committed listener to do two things; first, to delve into the record’s history via a generous smattering of demo recordings, and second, to re-think whether or not it was a good idea to dismiss the last Yeah Yeah Yeahs record, the sorely underrated Mosquito, out of hand based on its daft artwork. It’s not as if there’s anybody else who directly compares to this particular group; they occupy their own, vital place in modern rock history, and Fever to Tell is still their masterpiece.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Tunde Adebimpe

Thee Black Boltz

Julien Baker & TORRES

Send A Prayer My Way

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE