Twenty years on, The Verve revisit the elegant maelstrom that closed the book on Britpop

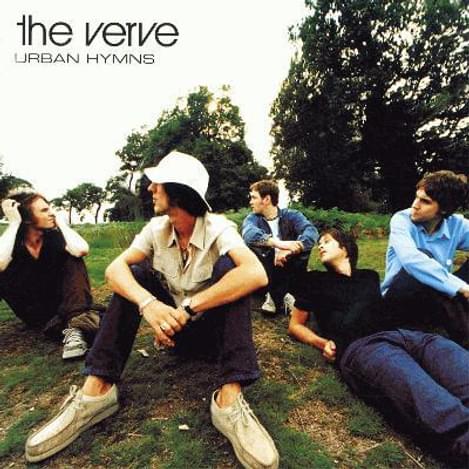

"Urban Hymns [Remastered]"

After all, by the time they’d released A Northern Soul in 1995, you would’ve gotten long odds on The Verve being the band to deliver Britpop’s swansong, not least because initially positive recording sessions were by the end chaotic, with frontman Richard Ashcroft frequently posted missing for days at a time. By the end of the year, the group had collapsed under the weight of Ashcroft’s famously tumultuous relationship with guitarist Nick McCabe, right when the single “History” was providing them with their highest chart position to date.

What happened next appears to have recently been subject to some outrageous revisionist history on the singer’s part. In an interview with Noisey last year, he insisted “the biggest albatross for me is that people think it took the other three - specifically Nick - to make Urban Hymns. If that was the impression, you couldn’t be further from the truth. Apart from obviously “The Rolling People”, “Come On”, “Neon Wilderness”, every other song on that record is just stone cold written by me.”

This is an assertion that begs a couple of questions. For a start, you have to wonder why Ashcroft reconvened with bassist Simon Jones and drummer Peter Sailsbury within weeks of the initial split, and then eventually asked McCabe back too, if Urban Hymns was supposed to be his first solo album. If these truly were his songs and his songs only, meanwhile, then that particular vein of creative form must have been quite the flash in the pan, given that his first three records were of decidedly changeable quality. It’s impossible to be so charitable about his most recent, last year’s These People, which was - not to put too fine a point on it - absolutely diabolical. Also worth noting: that run of Ashcroft’s own releases was interrupted only by The Verve’s 2008 comeback LP, Forth, which was miles better than it ever got credit for and certainly an improvement on his individual output.

Ashcroft namechecked those three songs because they’re the ones on Urban Hymns on which McCabe’s influence is the most obvious; they’re all epic, psych-tinged affairs that recalled the cacophony of guitars that characterised the band’s debut, A Storm in Heaven. Elsewhere, the focus was on a new sonic palette. There were tastefully implemented strings, something the listening public were in dire need of a reminder of - Urban Hymns was released mere weeks after Oasis’ Be Here Now. The guitars were being used more for colour and punctuation than anything else, lending an ambient feel to the likes of “Catching the Butterfly” and “One Day”. There was room for forays into experimental territory, too; the shuffling percussion on “This Time”, burbling away under twinkling piano, is almost downtempo, whilst “Neon Wilderness” serves as a woozy, avant-garde interlude close to the album’s midpoint.

Sealing the deal, though, were the big-hitting singles; they, ultimately, are the reason why Urban Hymns is the eighteenth best-selling record of all time in the UK. “Bitter Sweet Symphony” neatly encapsulates the album’s sonic ingenuity, sampling as it did an orchestral cover version, unrecognisable from the original, of The Rolling Stones’ “The Last Time” and creating one of the most genuinely iconic string parts in modern music history.

The band’s accountants, of course, would argue that they were too clever for their own good, with the song's royalties now absurdly ending up in the pockets of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards for no other reason than that Allen Klein, the deeply unscrupulous publisher who owned the rights to “The Last Time”, decided to rip off Ashcroft for the sake of it, just because he could. The rights to "Bitter Sweet Symphony" were ultimately signed away for a mere thousand dollars - ironically, Klein had burned the Stones in similar fashion back in the day.

Still, the track played no small part in making Urban Hymns the towering commercial success that it became, and the same can be said for “The Drugs Don’t Work”, one of Ashcroft’s finest ever lyrical compositions for its desperate candour, and “Lucky Man”, the loveliest of a clutch of elegantly earnest songs on the album’s back half that Ashcroft penned as straightforward paeans to his wife, former Spiritualized keyboardist Kate Radley.

It’s perhaps those tracks - “Space and Time”, “One Day”, “Velvet Morning” - that best explain why Urban Hymns provided such a neat signifier that the Britpop era was over. The willy-waving and misplaced machismo of the chart battle between Oasis and Blur in 1995 had driven both bands to opposite extremes - the former painting themselves into a cocaine-fuelled corner with the bloated lunacy of Be Here Now, and the latter moving towards indulgent impressionism never likely to appeal to the public at large. The Verve used smaller measures of each to create something that incorporated both Oasis’ anthemic sensibilities and Blur’s musical ambition, and blended them together with limitless heart and empathy.

This twentieth anniversary reissue of the album is suitably epic in its presentation, although anyone who doesn’t consider themselves a Verve diehard may find much of it to be extraneous. The fourth of the five discs is the highlight; for the first time, we get the entirety of the band’s massive homecoming set in front of 30,000 people at Haigh Hall Park in Wigan in May of 1998. It finds them at the absolute height of their powers; after all, Urban Hymns was a record that was supposed to be played to crowds of that size.

Disc five, meanwhile, provides as good a primer as any on the group’s earlier work across the course of three shows in Manchester, Brixton and Washington D.C. - there’s a particularly incendiary version of “A New Decade” that tells you a lot of what you need to know about McCabe’s penchant for oceans of reverb pre-Urban Hymns. Discs two and three comprise BBC session material as well as all of the album’s B-sides, which are interesting for their tonal similarity to the rest of the record - there’s no regression to the bombast of A Storm in Heaven or A Northern Soul.

Most important, though, is the record itself, and what a defiance of the odds it continues to represent. It’s not just that The Verve never looked especially well-placed to make the last great Britpop record. It’s that, whoever ended up making it, you’d never have expected that whole era to end quite this gracefully, not with Oasis’ faux-hooliganism or Blur’s art school sneer but with a full-throated roar of emotional honesty. Whether or not it came together in spite of the differences between Ashcroft and McCabe or because of them is besides the point - however it happened, they captured lightning in a bottle here, and closed the book on Britpop in the process.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Prima Queen

The Prize

Femi Kuti

Journey Through Life

Sunflower Bean

Mortal Primetime