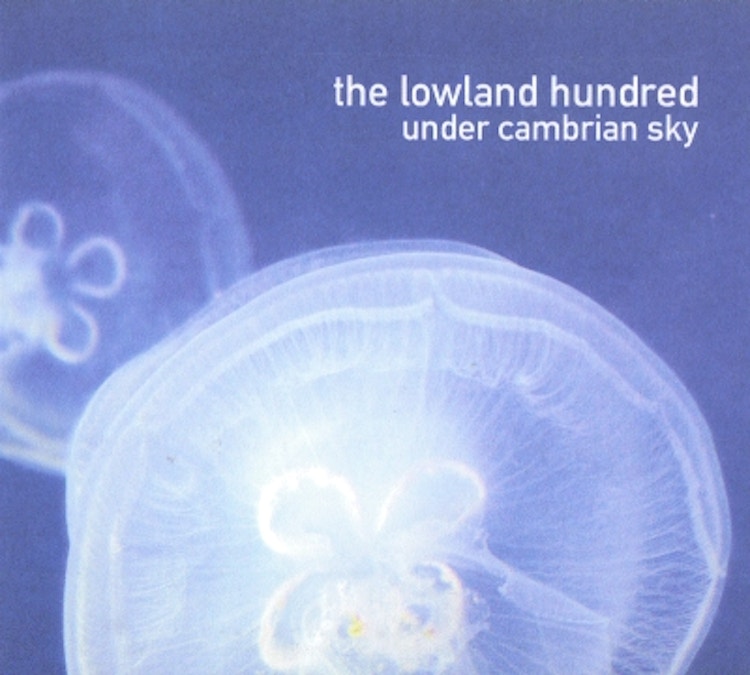

"Under Cambrian Sky"

All symptoms are a kind of geography; they take a person in certain directions, to certain places and not to others – Adam Phillips

The Lowland Hundred are the duo of Tim Noble and Paul Newland, currently based in Aberystwyth. They’re named after an area of west Wales that was destroyed by floodwaters in the mythic past. Under Cambrian Sky is their first album, and is a response to the lie of the land (can it be that I’ve never thought about that phrase before?) – both material and immaterial. What the album seems to be performing is a kind of mythic dredging, re –populating the lost landscape and exploring the spectre of place, and the ways in which this absence works a melancholy into the surrounding existing landscape, namely the seaside towns of the area around Cardigan Bay. It makes for a spooked and oddly beautiful album, out of time, full of Romantic longing and placeless nostalgia.

The land destroyed by floodwater seems to be something of an ur-myth, one that is popular across all cultures and periods of history (how’s this for a list?). To add to that exhaustive list, I’ve personally heard it spoken in hushed tones about the land between Land’s End and the Isles of Scilly and more recently there was the deliberate flooding of the Derbyshire villages of Derwent and Ashopton, to make way for the Ladybower reservoir, a situation mirrored in the Australian film, Jindabyne. There’s not really enough space here to worry at why such a collection of myths might have such a pull on our collective imaginations (aside from the idea of the displacement of populations and beliefs, is it a simple myth of cleansing? or given that so many of these myths feature the sounds of spectral church bells, something more figurative like the deluge of our unconscious minds working against the bonds of the super-ego in the guise of the strictures of the church?) suffice to say that the myth has a depth of resonance that speaks both to singularities and beyond site specificities.

There are several variations of the legend that surrounds the destruction of the lowland hundred or the Cantre’r Gwaelod in what is now Cardigan Bay in western Wales. The land was purportedly the most fertile and the most productive in the whole country, but due to its proximity to the sea, was under constant threat of flooding. One Seithennin, friend of the King and renowned heavy drinker, was in charge of the dyke that controlled the amount of water running into and out of the area and by all accounts he was in dereliction of duty on the fateful night, either because of booze intake or due to attending to the needs of some fair maiden. Whatever the reason, the dyke remained open and the sea came crashing through the dyke onto the land, drowning hundreds and devastating some 14 villages. An extraordinary passage by the Rev. G Edwards in an account of the events called The Lowland Hundred, written in the 1840s, tells of how ‘the flood gates were left open and the sea burst in upon the inhabitants many of whom were buried beneath its waves whilst revelling at their banquet and leading in the dance and their songs of joy were turned into a midnight cry’. Legend has it that if you’re in the area on a quiet day you can still hear the cries…

Sonically then, The Lowland Hundred deal very much in such a mode of quiescence – as if the album might be both a haunting and a kind of studied listening. The 7 tracks are constructed from very little – a series of simple piano figures and Tim Noble’s glassy Wyatt-esque voice tend to dominate, backgrounding occasional swells of feedback and the distant hum of wildlife and weather patterns. And thematically, aside from the over-arching subject of the deluge, the tracks tend towards the painterly, with ‘Camera Obscura’ particularly, detailing visual vignettes like ‘children paddling in the Irish Sea’ and ‘starlings roosting underneath the eaves’. ‘The Bruised Hill’ is lyric-less but follows a similarly painterly pattern using field recordings and gentle swells of guitar to great effect. When the moment of deluge arrives then, near the very heart of the album, in the track ‘Picot’ it comes with the requisite amount of shock – the inrush of water coming with a pounding of atonal bass piano notes. The word picot is a diminutive derived from the French verb piquer, meaning ‘to prick’, and like Roland Barthes’ punctum – a figurative wound or piercing caused by a work of art of piece of music – this is a central vortex that drags everything else towards it, a happening that grants the rest of the album meaning.

The odd track out is also the album’s longest. ‘The Air Loom’ is a 12-minute Musique concrète response to the story of James Tilly Matthews, an 18th century political provocateur who became convinced that the government were controlling his mind – and others around him – via the use of a mind-influencing machine, a huge loom that pumped ‘air’ into the ether directed towards specific people and was capable of all manner of tortuous influences, mental and physical: Kiteing, Bomb bursting, Lobster cracking, Thigh Talking, Fluid Locking and Lengthening the brain. Unsurprisingly, though his descriptions were meticulous and almost awe-inspiring in their invention, Matthews was sectioned and holed up in Bedlam, then a ramshackle place of gothic horror in Moorgate (Hogarth’s recreations of Bedlam for his Rakes Progess series for all their satiric intent contain a genuine sense of madness and horror). Here the work of the loom (and Matthews’ reputed madness) is mirrored with all manner of field recordings, whispered voices and manipulated machinery, to create a quietly unsettling piece of work.

That I’ve now crapped on for the best part of a 1000 words about this record is testament to the fact that a) I can’t help but run at the mouth with this stuff, stuff that tracks our melancholy obsession with place and displacement, our obsession with ghosts – historical, ahistorical – our obsession with a shared cultural heritage that’s both specific and universal, and b) that there’s so much to say. But I’ll shut up now and just ask that you track this down – it’s too intriguing and odd and too damn good to miss.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Prima Queen

The Prize

Femi Kuti

Journey Through Life

Sunflower Bean

Mortal Primetime