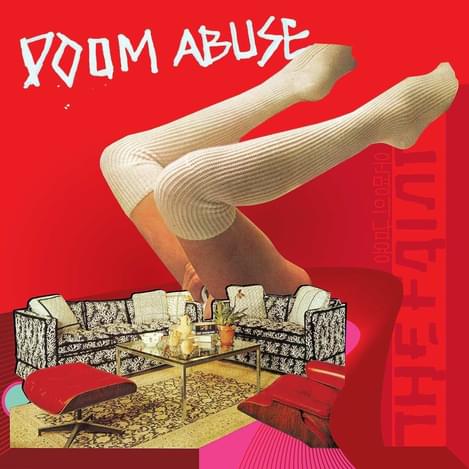

The Faint - Doom Abuse

"Doom Abuse"

Doom Abuse, the exceptional new album from Nebraska-based electro-anarchists The Faint, finds similar electricity in similarly coating the tools of dance and punk music in flammable spray paint. More barbed and acidic than the band’s most lauded album, 2001’s Danse Macabre, and more consistently thrilling than its previous high-water mark, 2004’s moody, prurient Wet From Birth, Doom Abuse is a starling burst of new-found energy (the record weighs in at a svelte thirty-five minutes), a revitalization project that hardly pauses for breath, that never settles for a clean space unmarred by sonic overload, the sound of computers corroding from the inside out. A neon collage of battered musical appliances superheated enough to bend to the shape of explosive energy, leftist avant-garde, and freaked-out cyberpunk, Doom Abuse is one of the most compelling albums of early 2014; one of the best records of the year so far.

Indeed, the screeching tangle of noise that begins “Help in the Head,” the album’s opening song and first single, even recalls the harrowing klaxons that began Yeezus. The song then bursts into a forward-assault dance punk, a mix of Tyrannosaurus Hives and Gang of Four, all brittle shards of bass and electric noise and singer Todd Fink’s high-attitude irony. That the song manages to be a mega-charged sprint of post-hardcore ferocity while constantly shaking up any resemblance of templated punk literalism (thanks to the waves of mussed sampler confetti that spark along the song’s surface) point to just how masterful The Faint have become at their own aesthetic. The band is nearly twenty years old, and has never approached this vitality, this level of fun.

The same goes for “Mental Radio,” three minutes of surf-rock run through a filter of Wire, The Cure, and Adam Ant. Less blistering, less volcanic than the best songs on the album, it is nevertheless a queasily overflowing canvas of diced-up styles and concerns, the song’s title chanted like a robotized Elvis Costello, stringy synthesizers twirling around the hook. Even better is the hyperactive apocalyptica of “Salt My Doom,” a marvelously quick punk song laced by unnervingly poppy keyboards, a redux of the band’s excellent “Dropkick the Punks,” the similarly severe hardcore blast from Wet From Birth. But where “Dropkick the Punks” felt like The Faint’s caustic sense of humor simply applied to someone else’s idea of punk rock, “Salt My Doom” is the sound of the band sculpting a futurist roadster out of their own electroclash spare parts. “Scapegoat,” from the album’s second half is similarly athletic, similarly bursting at the seams (the song sounds like a This Year’s Model track set to 45RPM), though with the added joy of the album’s most committed hook, a moment of major key ebullience that sounds glad to be thrilled instead of terrified to let its ironic guard down.

“Animal Needs” finds the band deep in the throes of Devo and their cyborg cubism, riding a quick-pedaling staccato with lines about the gap between humanity’s animal instincts and the incompatibility of technology: “We don’t need servants / We don’t need rules / We don’t prophecies ending in doom / Worn by humans, born like meat / Primitive culture for minimal beings / We got animal needs.” It’s hard to know what way to have The Faint on this narrative, so long is their history of irony, sarcasm, provocation, and the song’s mix of prizing humanist freedom (“We don’t need prophecies ending in doom”) with the potential fascism of “animal needs” is a bit confused, but if The Faint’s aim is to unsettle us with the added cognitive dissonance of making us move, then they’ve certainly achieved that much.

The rest of the album largely fits this aesthetic – songs that could have easily been poptimist club bangers, sere Dischord post-hardcore math lessons, down-the-middle punk pot-boilers, but that instead blur those lines in a post-modern neon haze. Perhaps the ultimate example of all of this is “Dress Code,” the albums shortest song (and, if you’re a fan of punk music, what you can assume will be its most severe, caustic), and one that begins with an atonal keyboard part that would have worked just fine as a Slayer lead before an ebullient undercurrent of hyperspeed disco rises to fill the song’s bottom half, a grinding wire of Fugazi bass rumbling beneath. Vocals arrive as computerized spoken word that sounds like David Byrne moonlighting in Daft Punk, listing the paraphernalia of middle class desperation through the stomach-ache warble of a vocoder. Push “Dress Code” hard enough in any one direction and it becomes something else entirely. The point is that, after a fitful career spent pounding at their own sound with a sledge hammer, then a disco ball, then a collector’s shelf worth of new wave records, The Faint have finally hit upon the idea of letting all of those varying sounds simply collapse in on one another, only to arrive at an album that sounds the most like them, even if we’ve never quite heard it before.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

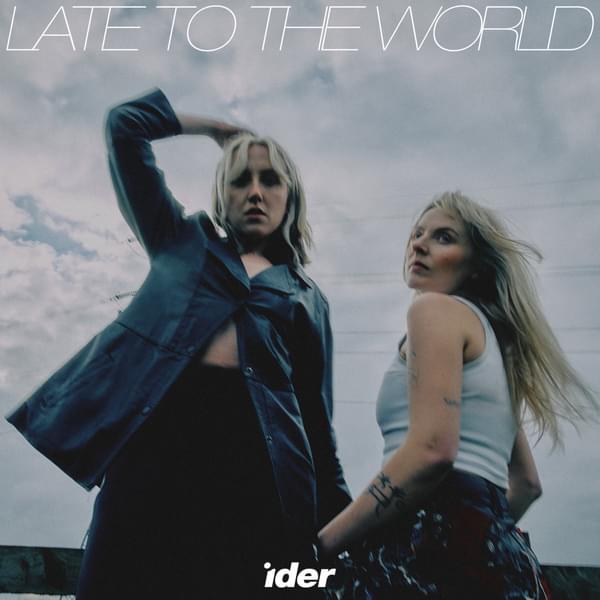

Great Grandpa

Patience, Moonbeam

Deafheaven

Lonely People With Power

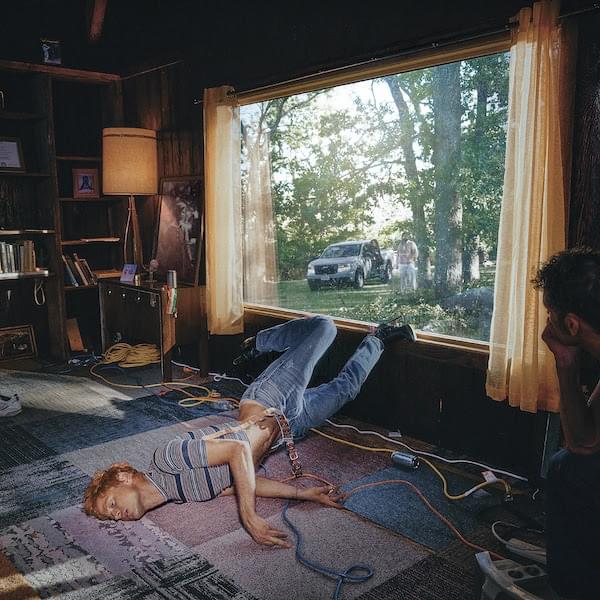

Perfume Genius

Glory