Taylor Swift's reputation is a microcosm of America’s explosive political landscape

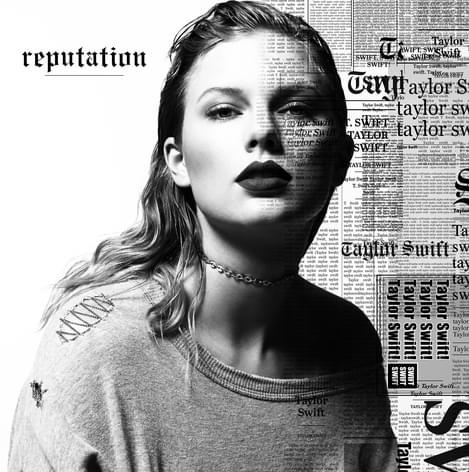

"reputation"

It should come as no surprise that steadily building political criticism of Taylor Swift has come to an incendiary head in a year when even Lana Del Rey has rolled up her American flag. A phrase that comes up again and again in recent writing about Swift is “lightning rod”. Her current legal battle with a left-wing blogger who accused “Look What You Made Me Do” of “affirming white supremacy” demonstrates the degree to which reputation is not so much a musical work as a microcosm of America’s explosive political landscape and the media's role within it.

Such a microcosm is far from utopia, and this is what Swift has lost by gaining hyper-relevance. In turbulent times, the second-most useful thing pop music can be - after political commentary - is a world to get lost in. From epics like “Enchanted” and “All Too Well” to the fizzy catharsis of “22” and “New Romantics”, Swift is a master at the pop art of building refuges of sparkle and storytelling amid the grey chaos of life. But this era is different. While reputation’s songwriting is mostly solid, it is weighed down by its cultural and political milieu. Sample line: “If a man talks shit then I owe him nothing / I don't regret it one bit 'cause he had it coming." Contextual reading: white pop star attempts to impose female-empowerment narrative into her unjust demonisation of already demonised black male peer. Escapist, apolitical, death-of-the-author reading: syllabically satisfying articulation of universal female revenge fantasy. Is the ten-foot chorus of “Getaway Car” enough to drown out the voice in my head going but why didn’t she endorse Hillary Clinton? How does a liberal person respond to an illiberal pop star? Further depletion of the outrage reserves? Or sheer, blinkered joy?

Realistically, it depends on whether the music is lyrically and sonically up to the task of escapism. reputation is a difficult album to love. 1989 captured the sonic zeitgeist - it arrived amid an eighties 'pure pop' renaissance, the richer, bitchier cousin of Carly Rae Jepsen's E.MO.TION, the mannered American ex-girlfriend whose nostalgic, iridescent synths shimmy their way through The 1975's I Like It When You Sleep... Part of what allowed it to do this was its cohesiveness. It felt decisive, like a manifesto. reputation, in contrast, is as polarised as it is polarising.

Much of its production feels passé. With the charts long saturated with EDM and Swift an established genre-dabbler, the dub drops of "I Did Something Bad", "Don't Blame Me" and "King of My Heart" were never going to be as bracing as "I Knew You Were Trouble" was in 2012. The Yeezus-aping electro-buzz of “…Ready For It?” and glassy atmospherics of “So It Goes…” (sadly not a four minute sequel to "Style"'s throwaway gem of Vonnegut appropriation) are interesting only on paper. Something more calculated and complex underlies the abrasive clatter of "Look" and "This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things", but they are not songs. They are extended subtweets, thinkpiece cannon fodder, news-cycle exhibitionism; bright, spiky things tossed into the gaping jaws of journalists and Swift's adoring legions. reputation's inexplicable track order likes to career between these blunt instruments and sparkly, specific moments like Swift's experiments with vocoder on “Delicate” and “Getaway Car”, or the way she helplessly draws out the word “gorgeous” in “Gorgeous”, or “Dancing With Our Hands Tied”'s molten-silver “oh, twenty five years old / oh, how were you to know?”. Similarly enjoyable are the Antonoffian touches – the echoing theatre of “Getaway Car”, and the emotive, "Perfect Places"-esque, Kanye-derived synth wheeze that lights up the second pre-chorus of "Call it What You Want”.

And then there’s “Dress”, a dancing-alone-in-your-room song of the first order. A choir of falsetto Taylors deliver the effortless slow-jam hook: “I don’t want you like a best friend / only bought this dress so you could take it off.” It perfectly catharsises the breathy, hilariously oblique sexual tension of "standing in a nice dress", and even "Dear John"'s tragic "girl in the dress". Andrew Unterburger writes that it feels “more like skin-shedding than clothes-shedding." The song's minimalism goes beyond restrained production: Swift is dropping narratives to the floor. It's hard to describe the sense of lightness as the deadpan "my hands are shaking from all this..." (!) explodes into the impossible effervescence of the chorus, or as the music drops out, "Sparks Fly"-style, for the last round, or how distant all of this feels from the heaviness of Swift's cultural baggage. It’s the only track on reputation that sounds like her future.

At her best, Swift is a great American writer. At her best, Swift at twenty-seven is Don Draper as a teenage girl: country bumpkin turned New York sophisticate, living from lover to lover, downing Old-Fashioneds, driving forever down indifferent highways, turning out million-dollar lines like "you made a rebel of a careless man's careful daughter" as if they'd been scrawled in her diary for years. But Swift refuses to fully embody that mythos. She's amazing when she's morally grey (see: "I've loved in shades of wrong", "I've been there too a few times", "should've known I'd be the first to leave"), but obsessively imposes fairytale black and white on her turgid dot-to-dot of celebrity feuds. She can make music that sounds like infatuation (see: the warm-blanket synths of "Call it What You Want"), but even then can't resist asides about liars and gunfights and kings and queens.

The Old Taylor is not dead, but she is buried. She pops in to tell a would-be lover “guess I’ll just stumble on home to my cats”, to conjure a devastating extended Bonnie and Clyde metaphor, to assert “candle wax and polaroids on the hardwood floor” as her new “refrigerator light”. It is up to you how much mediocre EDM and fetishized victimhood you are willing to endure to reach her. Because ultimately, the approximate third of the album that Swift spends railing against an evil, ill-defined "they" renders the whole thing close to emotionally impenetrable. A few years from now "Look What You Made Me Do" and "This Is Why We Can't Have Nice Things" will be mere artefacts recovered from a queasy, exhausting headline tyre-fire. The songs that stand a chance of enduring ("Delicate", "Getaway Car", "Dress", "New Year's Day") are those that take place between two people, in a dark room or car far away from the "tilted stage" of public opinion. In short, reputation's best tracks are those which undermine its central conceit.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex