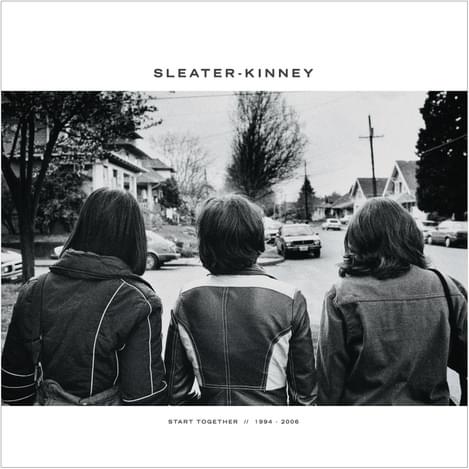

Sleater-Kinney - Start Together [Reissues]

"Start Together"

It actually felt like a bit of a revelation to speak to somebody who heard the word ‘reissue’ and immediately thought of the practical purpose; putting music into the hands of people who’s otherwise struggle to track down a record that was rare and out of print. These days, of course, the concept has been commercialised more crassly than Christmas. There’s the constant cash-ins on ‘classic’ albums, like those recent re-releases of the first two Oasis records that were so redundant in terms of value for money that even the Gallagher brothers, not usually known for sensitive gratitude when it comes to their fans’ hard-earned cash, urged their supporters not to buy them. Another new trend that leaves a sour taste in the mouth involves putting out ‘deluxe’ versions of albums when the original’s barely been out a year; that new Wild Beasts record is great, but did we really need a repackaged version with a few remixes tacked on after six months?

All of that said, I still can’t find adequate reason to pick fault, on that front, with Start Together. Despite lavish critical acclaim following them from pretty much start to apparent-finish over the course of their twelve-year career, it’s hard to shake the sense that Sleater-Kinney remain underappreciated. Their influence on contemporary indie rock is glaringly - and increasingly - obvious, but it’s not all that often you hear them cited as an influence by new bands. I wouldn’t ever want to think of the wider promotion of their work as a bad thing, and it’d seem pretty self-defeating to overlook the opportunity that 2014 presents for that, as the twentieth anniversary of the band’s formation.

Which is why it’s a delight to report that Start Together is as lovingly put together as any reissue series that lingers in recent memory. The seven-LP boxset, with the vinyl pressed in a gorgeous array of colours, is a fittingly grand way to present the albums that, together, constitute the story of one of the great American rock bands of recent times. Sleater-Kinney were born out of socially-conscious roots; Corin Tucker and Carrie Brownstein were both in bands largely defined by their sexual and gender politics when they launched this new side project in the punk Mecca of the pacific northwest, Olympia, in 1994; accordingly, their furious self-titled debut can very much be considered a product of the scenes that Tucker and Brownstein were a part of at the time. It was released, originally, on Chainsaw Records, a predominantly queercore imprint that had also put out records by The Fakes and Brownstein’s old band, Excuse 17; in retrospect, Sleater-Kinney is hardly out of place amongst such company. It’s blisteringly quick, clocking in at a little under twenty-three minutes, the production is relatively rudimentary, and there’s no shortage of aggression in the vocal lines that frequently overlap between the two main players. Lyrically, we’re firmly in riot grrrl territory, and whilst that particular scope would widen for the band as the years rolled by, it’s obvious - especially in retrospect - that Tucker and Brownstein had already established the basic sonic blueprint for the band as early as this first full-length.

That probably goes a long way to explaining why they were able to deliver a second record as confident as Call the Doctor; they already had the fundamentals in place, and as such, they evidently viewed album number two as a platform for experimentation. It’s the first record on which it began to become abundantly clear that Brownstein, as a guitar player, was talented beyond the fairly restrictive environment in which she’d previously been working; the crunching, smartly layered lines that characterise her playing on this album pretty much define its sound - they’re imbued with the same energy as Tucker’s tirelessly dramatic vocals, but throw up enough new subtleties with each listen that there would’ve been no real way that anybody who’d dismissed Sleater-Kinney as sounding relatively by-the-numbers, by the punk standards of the time, could level the same accusation at Call the Doctor. “Heart Attack”, in closing the album, is probably the track that sums it up best; Tucker veers between sweetness and screeching, and Brownstein matches her, a melodic riff battling the rhythm guitar for prominence throughout.

The overwhelming impression that you come away from the album with is one of a band applying considerably more intelligence to their music than most of their peers, without ever wanting to look as if they were trying to cast off the punk tag. Thematically, it’s probably the first album of Sleater-Kinney’s where you can begin to pore over the finer details of what the lyrics can tell us about the relationship between Tucker and Brownstein, one that they’ve both been notoriously vague about since Spin outed them as a couple in 1995. We can probably assume that was the state of play during the making of Call the Doctor, as well as take it as read that it was a tumultuous relationship; the simmering tension that runs right through the record, the belligerent nature of some of the vocal back-and-forths and lyrics that swing between obvious passion - the title track - and ambivalence - “I’m Not Waiting” - suggest that the pair really were veering between those kinds of emotional states whilst they were putting the album together.

Of course, Call the Doctor also spoke to the bullishness with which Sleater-Kinney presented their ambition; both the title of “I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone” and Tucker’s proclamation on that track that she was “the queen of rock and roll” were pretty clear indicators of that. It was a theme that continued with Dig Me Out, the album that cemented the band’s place not only as critical favourites, but as one of the most forward-thinking rock outfits in America. Tucker was only too keen to use extra-curricular platforms to spell out the group’s aspirations - “I find it kind of ridiculous when people fear the future. We are the ones who are going to create it,” she told Rolling Stone - but you have to wonder whether that was really necessary; Dig Me Out is delivered with such verve and self-assurance that you only need to listen to it to know that Sleater-Kinney were in no doubt whatsoever about the path that they were on.

In many ways, it’s a pop record - in the same way that Nevermind is compositionally a pop record, or Flip Your Wig, for that matter. Brownstein’s melodic brilliance with the guitar continues - she runs the gamut form low-key, noodling work on “Dance Song ’97” to full-on freewheeling on the bratty thrash of “Not What You Want” - but the real shift on Dig Me Out is the copious amount of to-die-for hooks; the sheer sass of “Turn It On” - those handclaps on the chorus - and the taut catchiness of the title track are cases in point. Again, the confidence that the record exudes at every point is key; at no point do you get the impression that Tucker, Brownstein and the newly-recruited Janet Weiss on drums really wrestled with the concept of moving in a markedly poppier direction; they just flat-out decided to go for it, and fucking own it. In doing so, they managed to not only maintain many of the key features of the sound that they’d laid out on their first two albums, but actually accentuate some of them, too; the highly intimate nature of their lyricism was broadened to make room for romanticism alongside the angst, and the increasing sophistication of both the production and the instrumentation was only furthered by the gravitation towards pop sensibilities and the addition, with Weiss, of a drummer with her own identity, too. Not that the typically intense interchanges between Tucker and Brownstein were done away with, though; “One More Hour”, about their breakup, has the latter countering the former’s wailing on the chorus with a deliberately blasé turn of her own.

The album that follows your critical breakthrough, on paper at least, should be the toughest; you’ve got to prove that, in fact, you have got somewhere other to go but down. 1999’s The Hot Rock actually predates PJ Harvey’s Stories from the City, Stories from the Sea by a year, but there’s some immediately obvious, superficial similarities between the two; both are sonically polished affairs that followed a series of rougher, rawer efforts, both have the artists in question standing in the street on their respective covers, and both can probably be pinpointed as the precise moment at which their creators could comfortably be considered amongst the finest rock acts that their respective countries had to offer. The Hot Rock is ostensibly named after the Robert Redford crime caper - or, at least, the almost-title track “Hot Rock” is - and whilst it’s been suggested elsewhere that it might also represent an oblique nod to The Rolling Stones, what’s always jumped out about that title to me is that the word ‘hot’ is a fixture of the Billboard charts in America; in fact, the rock chart remains known as the Hot Rock Songs rundown, and irrespective of how The Hot Rock actually did fare commercially, it definitely feels like the first Sleater-Kinney record that was far enough removed from the punk abrasiveness of their beginnings to actually have a shot at cracking the mainstream.

That’s not to suggest that it isn’t replete with their trademark ferocity, of course; in fact, if this album feels like it doesn’t quite hit the same breakneck pace as its predecessors, it’s likely down to the increasing complexity of the songwriting. Brownstein uses the lead vocal slots she’s afforded to display a tenderness that doesn’t, for the first time, feel as if it’s simply being included as a deliberate counterpoint to her more confrontational efforts; the gorgeous “The Size of Our Love” uses terminal illness as its backdrop to arresting effect, marking another extrapolation of her lyrical approach. It seems fitting, too, that it’s one of a handful of songs on The Hot Rock to include snatches of a string section; as with the move towards pop territory on Dig Me Out, the restraint and cleverness with which the strings are utilised suggests that there was probably no deliberation behind what their inclusion would ‘mean’ for the band’s sound - it’s hard to imagine they’d ever shy away from a marked shift in tone, so long as it represented the best way forward for them creatively. There’s still flashes of the old Sleater-Kinney in there, too - “Burn, Don’t Freeze” and “One Song for You” prove that the aggressive, crossed-over double vocal dynamic was as sharp as ever - but the album’s signature moments come when that dichotomy is developed in accordance with The Hot Rock’s new sonic direction; closer “A Quarter to Three” provides a fine example, as well as what sounds like a weirdly well-suited accordion in the final seconds, too.

If there is a Sleater-Kinney record that can be designated as the catalogue’s watershed moment, it’s probably All Hands on the Bad One. That’s less in terms of obvious sonic or thematic change - in that regard, it’s likely less revolutionary than either of Dig Me Out or The Hot Rock - but its significance, both at the time and in retrospect, relates to the fact that the trio are amongst an elite band of groups who can boast a track record amongst which even the weakest moments couldn’t really be appraised as being less than pretty good. In most of their peers’ cases, though, that was usually because of the brevity of their lifespan; Noel Gallagher once said that The Smiths “must never have been shit”, but they were only together for five years, and there’s probably a compelling argument for Johnny Marr having thrown himself on the grenade by leaving the group before Morrissey could lead them too far down a bleak path paved with Cilla Black covers. Sleater-Kinney were into their seventh year together as they released All Hands, and the fact that this record is probably as close as they ever came to treading water is both remarkable and clear evidence that they were subscribers to the Woody Allen view on sharks, movement and death.

All Hands was evidently written pretty quickly - it’s easy to forget that, circa 2000, the band were relentlessly on the road - and whilst that means that any aspirations they might have had to further the explorations of The Hot Rock were largely curtailed, it still stands out in the canon not only as one of the most energetic albums the band made - the trademark crackle and fizz is here by the spade - but also as one of the most thematically interesting, too. There’s probably a discussion to be had about whether a band who could boast a critical copybook as spotless as Sleater-Kinney’s should really be biting the hands that have typed so many ringing endorsements of them with songs like “The Professional”, but that apparent pop at rock critics is hardly the most important issue addressed here; the bullish one-two of “Was It a Lie?” and “Male Model” offers up different angles on the treatment of women by the media, whilst “#1 Must Have” goes a step further, addressing the general perception of riot grrrl typically acerbically and closing on a powerfully positive note - “culture is what we make it, yes it is/now is the time to invent”. It’s a sentiment that chimes with All Hands in general, too, because there are progressions here; they’re just subtler than before. Weiss’ elevation to backing vocals lent them another dimension by opening up the possibility of harmonisation, and the reintroduction of John Goodmanson behind the desk was a masterstroke; if you’re going to make a record that feels this spontaneous, you should at least have production duties handled by somebody with an uncanny talent for capturing the zeal of your live shows.

I could also talk about the steady progression of Tucker’s increasingly flexible vocal ability across The Hot Rock and All Hands on the Bad One, but there were plenty of more pertinent reasons behind the fact that One Beat felt like an album that charted her personal development more closely than any other she’s been a part of. She became a mother for the first time during the album’s gestation; that’s the kind of profound shift that’s always bound to come with its own set of anxieties, but in Tucker’s case, they were amplified considerably by the fact that her son was born nine weeks premature. Pair that situation with the fraught political climate that also came to frame One Beat’s development, and you realise that this is the record that saw Sleater-Kinney knock down one of the few remaining walls between themselves and their audience; they’d never made an album before that was so explicitly influenced by an event entirely outside of their own ecosystem, but then of course Sleater-Kinney would make a record that tackled post-9/11 America head-on. The usual rules never really had applied to them, after all; you rather suspect that they largely regarded as cowardice what most other bands would merely deem prudence. One Beat is the sound of a rock and roll band taking the anger, worry and - most of all - the sheer uncertainty of their country in the immediate aftermath of September 11 and converting it into a genuinely irrepressible energy.

It’s funny; now, you hear a Bush-barbing lyric like “and the president hides, while working men rush in and give their lives”, and it sounds tame and tired; place “Far Away” in context, though, and you remember that it was written at a time when attacking the commander-in-chief was borderline sacrilegious - just check Bush’s approval ratings from around the time of One Beat’s recording for proof. Once again, then, Sleater-Kinney were blazing a trail with the clutch of overtly political tracks on this album, but its most affecting moments still come in something like typical fashion for the group; their best lyrics were always the ones hammered home on a personal level. It’s the image of Tucker watching the towers fall whilst cradling her impossibly-frail newborn that stays with you long after the closing bars of “Sympathy” ring out, and it’s because of that kind of deeply personal storytelling that you know that, more than ever, Tucker fucking means it on this record; the profundity of its catharsis for her is what gives it its identity amongst the band’s other records. Strip away the context, and you’re still left with a remarkably tight punk record that continues to refine Sleater-Kinney’s penchant for balancing the sweet with the caustic, but listen to One Beat with a proper understanding of the circumstances surrounding it and you realise what a devastating piece of work it really is.

If there was devastation associated with The Woods, meanwhile, it likely came years after its 2005 release, once the realisation began to set in amongst fans that it might actually represent the trio’s swan song. You might look at the red curtains that frame the cover art’s stage, assume them to be closing, and take that as a clever wink goodbye on the band’s part, but pretty much nothing else about The Woods really suggests that anybody really knew it would be the last Sleater-Kinney record for a long time. For one, it saw them finally make a step up in business terms, from a small independent label - Kill Rock Stars - to a bigger and frankly perfectly suited one in the form of Sub Pop. John Goodmanson’s abilities as a producer, meanwhile, were dispensed with, and given that he was working with a band who never, until now, seemed to have even flirted with the idea of looking backwards, he perhaps shouldn’t have been altogether surprised by the call. Instead, Dave Fridmann - the only man ever really widely accepted as being warped enough to be up to the task of producing albums by The Flaming Lips - took on the role, despite professing to be reasonably ambivalent about the Kinney catalogue to date.

We can probably safely assume that Tucker, Brownstein and Weiss took Fridmann’s apathy to represent a frankly heinous level of disrespect, because The Woods is a work of utterly vicious intent. The extensive touring schedule for One Beat had seen the trio play to arenas across North America in support of Pearl Jam, and it’d be remiss of me not to acknowledge the influence that clearly had on the sound of The Woods; everything feels grander and more expansive than ever before. The real driving force behind the record, though, sees yet another left turn for the band; they’re in thrall to classic rock influences for much of the album, a move that perhaps sounds incongruous on paper, but works perfectly in practice. There’d always been a touch of Robert Plant to Tucker’s vibrato, and she takes the parallel to a glorious extreme as she shrieks her way through incendiary opener “The Fox”. Brownstein, meanwhile, is in her element mining these kinds of archives; “What’s Mine Is Yours” is a bluesy stomper, “Wilderness” is built around some huge, distorted riffery, and “Night Light” proves she’s more than capable of adapting her penchant for setting a melodic, picked guitar line against a noisy rhythm one, too; the crispness of the tone she brings out of her instrument throughout the record probably represents her high watermark across any of the seven albums. You could probably say that about Weiss’ work on the record, too, especially on the epic “Let’s Call It Love”, which boasts one of the most complete drum performances I can recall.

A quick note on the remastering here, too; nine times out of ten, it feels as if the very concept of putting old records through this particular process amounts to little more than a branding move, given that you’d usually need to be an audiophile to really be able to discern the differences. The Woods, however, is one album that I’d always thought might have benefited from being mastered just a touch quieter, even if I can fully understand the rationale behind making it so fucking loud in the first place. This new release delivers to that end, taking a little bit of the edge out of the volume whilst retaining the sharpness that characterises the record; The Woods aside, though, the only other album on which the difference between the original and remaster really leapt out at me - and only at certain points - was Call the Doctor.

I suppose the bottom line on Start Together is this; ‘reissues’ like these are usually exercises driven purely by profit, that should appeal exclusively to diehards. That should be especially true in the case of a box set like this one; after all, how many bands make seven records and don’t turn in at least one that’s distinctly average? On Start Together, though, it’s not just that all seven albums are of serious musical worth; together, as the Sleater-Kinney back catalogue, they feel like they have some genuine historical value, too. As fate would have it, the band rendered my original conclusion for this piece null and void last Friday night when it emerged that the set includes a seven-inch containing a new song, “Bury Our Friends”, that’s labelled simply ‘1/20/15’; it's now been revealed that their first LP in just shy of a decade will drop on that date, and be titled No Cities to Love. In retrospect, I already feel daft for thinking that they could release something that did nothing but look backwards; the fact that they’ve only ever moved forwards, usually with an aggressive intensity, explains how they managed to achieve such a genuinely unblemished track record first time around. There might well be plenty of other bands who could have commanded the same level of respect and deference if they’d just managed to have the courage of their convictions from their very first practice to their very last festival slot, but they didn’t; that kind of integrity is as rare a commodity as ever these days. Sleater-Kinney did, though, and Start Together is indispensable.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Great Grandpa

Patience, Moonbeam

Deafheaven

Lonely People With Power

Perfume Genius

Glory