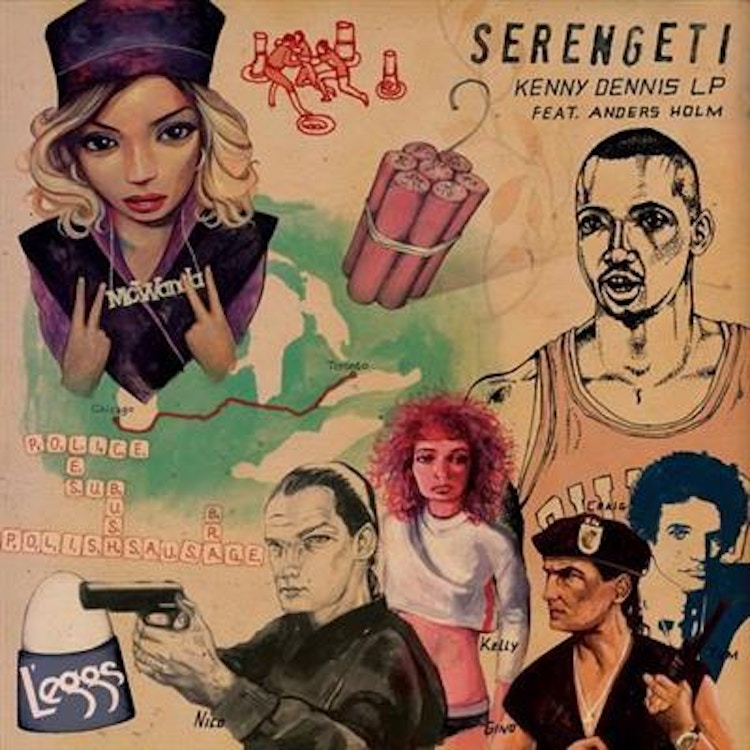

"Kenny Dennis LP"

Bang, bang. That onomatopoeic pairing has two meanings in Chicago, the interrelatedness of which depends primarily upon the emphasis one places on various socio-cultural/socio-economic factors in regards to artistic expression; namely, does art inspire, perpetuate, and/or glorify violence, or merely reflect it? Bang, bang is, of course, the sound a firearm makes when discharged, and I can speak from personal experience when I say that it is a quite distinct and terrifying sound, carrying some sort of un-placeable bite which makes it distinct from its harmless mimics, e.g., firecrackers, cars backfiring, any number of multifarious snapping sounds, when heard in an urban setting (perhaps the only sound more horrific is the distinctive chopchopchopchopchop of an AK-47, which I have heard once, from a rooftop in North Philadelphia, smoking blunts and hucking beer bottles as javelins on a tactilely oppressive summer night). It is also, in a city synonymous with gun violence in a country synonymous with gun violence, an all too ubiquitous sound.

Bang, bang is also the primary ad-lib of Chief Keef, l’enfant terrible of rap and crown prince of Chicago’s drill scene and, depending on those aforementioned views regarding race/culture/city planning/economics/violence, provocateur and glamorizer of Chicago’s insatiably blood-thirsty and gleefully wasteful regard for (poor and predominantly black or latino) life, or unblinking harbinger of a world the rest of Chicago–particularly that of the Powerful–choose to believe does not exist.

There is of course another, more benign meaning of bang to be found, in idioms and on sports pages: bang it out, banging down low in the post, he’s a real banger, banged up–all connote hard work, grind, City of Big Shoulders, pork butchers and railroad yards and pushing upwards towards the sky, forging and then placing a great giant saw-toothed inland crown upon the fierce climes of the North Coast, one of four points on a compass demarcating the brutal subjugation of the vast savage torso of North America; that is the bang which Kenny Dennis espouses.

That is, in fairness, probably a far too-complicated reading into of a joke (and make no mistake, Serengeti’s Al Bundy-cum-Humpty Hump emcee is indeed a joke; a well-written expository vivisection from Jeff Weiss can be found here, and should be considered requisite reading for the remainder of this review), but comedy–particularly hip-hop comedy–serves us either through relevance, irreverence, or a combination of the two, and it is to Serengeti’s great credit that Kenny Dennis can exist most anywhere on that spectrum.

Serengeti’s middle-aged alter ego could benefit rap as a whole merely through his existence; this is, after all, a genre whose ludicrousness is matched only by its solipsism, and any caricature which can inject even a modicum amount of uninhibited fun into the proceedings is a welcome figure. But Kenny Dennis is more than that; the clumsily worded pep talk (“Uh, it’s a metaphor for life! You gotta get out and do something! You gotta get out and do something! You gotta get up and do something! You bang ‘em! You like it, you bang it! Sometimes you don’t wanna go to work, but you still gotta bang it!”) which closes ‘Bang em’ is inspiring despite itself, even if delivered in an accent thicker than Da Super Fans and with the same halting, irregular cadence as their hearts. Similarly ridiculous and cockles-warming is ‘Kenny and Jueles,’ wherein Dennis plumbs the depths of human relations, admitting in turns that Jueles sometimes leaves him “stupid stressed” while sacrificing a spot as an American Gladiator–earned by ably humiliating gladiator Nitro in Powerball, joust, and the Eliminator–in a prime example of “love and devotion and sacrifice.”

A near perfect analogue for Dennis’ curious ability to engender empathy–he is the joke you laugh and feel with–can be found in, of all people, Rick Ross. Ross, the one whom William Leonard Roberts II has painstakingly cultivated, the Teflon Don cocaine mafioso of Miami, is nearly as much of a fictional construct as Kenny; any idea that he knew the real Noriega was fairly well defenestrated with the discovery of Robert’s former life as a corrections officer. Still, Ross’ continued success after such prima facie suicidal revelations speaks volumes as to where rap, and the average connoisseur there of, have found themselves post-gangsta and post-politics. Technology has turned rap music into the most populist of art forms, with a vast array of voices springing like anemone from the blood of the old machine. The means of production and promotion have been loosed upon the people, and the people have utilized it to articulate positions and personalities of one’s wildest dreams. In such a landscape, where the eloquent harlequins Das Racist lacerate, Dadaist Riff Raff gleefully titillates the very boundaries of rapping, and Tyler, The Creator can turn Beautiful Violence into an Empire, there is indeed room for a man simply playing at drug czar, provided he play it well enough; recognizing a masterful piece of acting when it was presented to them–the brilliance of Teflon Don, really, is the other key component to Ross’ recovery; had it not been so convincing, so luxuriously enthralling, that C.O. past may have doomed Ricky forever–the critical and commercial spheres embraced Ross, history and all, and have been rewarded with the continuing crucibles of a man so outlandish he could hardly be real, perhaps with the tacit realization that only such a figure could carry enough drama to slake us.

In this regard–creating feeling through sheer Jovian dominance–Serengeti differs from Ross greatly; in style and tone, eve more so. Kenny Dennis is exceedingly difficult to fully comprehend on his eponymous LP, that wet-meat-hitting-countertop accent combining with sputtering, curiously sauntering flows to create raps which sound like a man struggling to move through molasses. Listening to Dennis struggle, hearing hints of his halcyon days with the Grimm Teachaz, is a key component to one’s enjoyment of Kenny Dennis LP; he vellicates and hiccups across an assortment of lo-fi beats and hearty boom-baps, spitting–hacking and coughing, really– humorous aspects of the mundane juxtaposed by the odd and dropping esoteric Chicago references, and every one in a while, he breaks free, pulls his feet from the muck, and takes off, in the gloriously ungainly and pleasingly brutish way of a Bulls era Dennis Rodman.

These moments are both exhilarating and absurd, the former because he can once again fly, and the latter because he of course never could to begin with. This is where Dennis and Rozay once again begin to dovetail; being born of imagination and fed by the muses, Dennis, like Ross, exists solely in the music; we find ourselves listening and caring about him because this is the only place in which we can care about him. Dennis is a fully fleshed out persona, an alter-ego which makes the myriad of masks worn by Nicki Minaj look like the creations of a budding actor in the midst of their first workshop. It goes far beyond a voice and a mustache, to tropes both stereotypical–his love for Chicago sports and Western Avenue (which is not too far from my apartment)–and abstruse, including beef with Shaquille O’Neal and an odd affinity for O’Doul’s non-alcoholic beer. Serengeti’s Dennis becomes a character out of Nine Stories; he is revealed to us in flashes and vignettes and anecdotes, and the desire to pin him down, if only for the duration of a Bear’s game, becomes inevitable.

Like any farce, the Kenny Dennis LP is something of an acquired taste, and if the recent existential contemplating all engaged with rap music have done upon being presented with, by the likes of Das Racist, Kitty Pryde, and Riff Raff, a mirror within which to see themselves is any indication, Serengeti’s masterful card will polarize as much as amuse.

Kenny Dennis is a joke, and, to paraphrase Weiss, “sometimes, you laugh or you don’t.”

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday