Record Store Day: Billy Bragg & Wilco – Mermaid Avenue: The Complete Sessions

""

Can a person’s life be defined by their art? This box set gives it a good go. In 1992, Woody Guthrie’s daughter Nora had contacted folk-punk stalwart Billy Bragg about the possibility of penning music for the hundreds of unpublished lyrics her father had left behind. Despite some minor concerns (“My initial reaction was, ‘surely this is Bob Dylan’s job,’” Bragg informed Billboard recently), the Bard of Barking agreed to throw himself into the challenge. He swiftly enlisted Wilco to act as both backing band and collaborators, with the Illinois quintet still very firmly in their post-Uncle Tupelo alt.country phase. Recorded over three separate sessions in Chicago, Boston and Dublin, the project birthed a surfeit of songs that were eventually cut down to a fifteen track album, released in 1998 and titled Mermaid Avenue after the Guthrie family’s Coney Island home.

Differing visions of how the record should interpret Woody’s legacy led to tension between Bragg and Wilco during the mixing stage, but nonetheless a second set of songs from the original sessions appeared two years later. With the inclusion of a handful of newly-completed songs, it looked as though this was the last we would see of the project. Until now, that is. In an unexpected bout of vault-clearing, the American band’s former label Nonesuch have compiled the earlier two volumes with a third and final selection of songs from the original recordings. With the inclusion of Kim Hopkins’ wonderful Man In The Sand documentary, Mermaid Avenue: The Complete Sessions is the closest we’re likely to get to a full picture of the whole shebang. And guess what? It’s pretty darn interesting.

Listening back to the original set provides a healthy reminder of why the album was so beloved when it first appeared. The rowdy gang vocals of opener ‘Walt Whitman’s Niece’ get us off to a fine start, before ‘California Stars’ floats dreamily through the West Coast sunshine, and before we realise it, we’ve already been presented with the different takes on Guthrie’s songwriting. Bragg takes the lead on the former, a hearty, drunk-sounding ramble through a fine lyrical conceit about detail, vagueness and meaning. Meanwhile, Wilco handle the second track with the elegant rawness of their Being There double album, revelling in uniquely American images and subsequently awestruck poetry. Both artists will explore different aspects of the folk singer’s verbosity as the album goes on, but even so, battle lines have swiftly been drawn between Guthrie as language-loving raconteur, and Guthrie as painter of powerful pictures.

Next up is one of the key tracks on the record, the yearning beauty of Bragg’s ‘Way Over Yonder In The Minor Key’. The author reminisces about his youth in Okfuskee County, Oklahoma – specifically how he charmed a young lady with the vain boast, “Ain’t nobody who can sing like me”. The Englishman seems to take the phrase to heart, perhaps acknowledging that his broad Essex vowels and forthright tone make his own vocal cords reassuringly unique. It’s worth noting, however, that throughout the Mermaid Avenue project, Bragg ditches his familiar voice to attempt an American twang. Is this an attempt to connect with the distinct culture depicted in the lyrics, or a misguided attempt by the self-described ‘progressive patriot’ to emulate his own vision of their voice? It’s unclear, which is presumably why he lands somewhere nearer to awkward transatlanticism than a genuine-sounding accent. It’s puzzling rather than intrusive, however, and there can’t have been too many distraught fans tearing their hair out at the prospect.

Among the album’s other significant moments, ‘Hoodoo Voodoo’ is worth mentioning for the dichotomy between the blustery thrill of the music and the near-twee, nursery rhyme-ish nonsense of the words (“Chugga-chuggy-choo-choo / True blue, how true / Kissle me now”, goes the chorus – admittedly, it was written for his children). Perhaps reflecting the more abstract lyrical avenues down which Jeff Tweedy began to embark on Wilco’s next two records, you might want to consider this as a possible demarcation point in their gradual transformation from shit-kickin’ country rockers to texturally-considered alt.rock veterans. With the two acts in apparent competition with each other for the remainder of the disc, the proto-feminist ‘She Came Along To Me’ and union-friendly rabble-rouser ‘I Guess I Planted’ give Bragg the edge, but the breezily adorable ‘Hesitating Beauty’ claims points back for Wilco. Happily, there are still treats-a-plenty thereafter too.

It’s perhaps inevitable that the second volume would pale in comparison. With a country-folk feel dominating proceedings, the original collection at least felt musically cohesive, whereas the follow-up has the air of an odds’n’sods compendium. ‘Airline To Heaven’ blows the doors open pretty neatly; a gloriously ragged stomper starring Tweedy’s best Tom Petty impression and a chorus that initially feels jarringly awkward, but inexplicably attains a laconic brilliance several listens later. It’s more obvious as to why ‘My Flying Saucer’ ended up here – despite a pop sensibility that’s both sterling and stirring, the jangling lead and shuffling rhythm sound more akin to Bragg’s solo work than the over-arcing motifs of the venture as a whole. Which is a shame, as the track’s analogy – likening a lover to an alien spacecraft – is endearingly daft.

Indeed, it’s easy to forget from time to time that the centrepiece of the collection is supposed to be Guthrie’s lyrics, particularly when the two performing factions have such disparate ideas of how to convey them. Guest vocals from Natalie Merchant and Corey Harris at least serve to refocus the listener’s perspective, and Harris’ boisterous run through ‘Aginst Th’Law’ is a welcome reminder that politically-minded witticisms needn’t necessarily be subtle. Wilco get all dreamily-romantic on ‘Secret Of The Sea’, mourning “The footprints of the lovers that come here to love / By the tides washed away forever more” over one of Tweedy and the sadly-departed Jay Bennett’s most strident melodies.

The less-enjoyable moments are scattered between both participating parties – in particular, Jeff’s monotonous drone on ‘Feed Of Man’ amounts to a needlessly dreary attempt at the tricks learned from Dylan’s ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’. Meanwhile the caterwauling backing for ‘All You Fascists’ may provide Bragg’s seething delivery with the necessary vim’n’vigour, but also veers dangerously close to Blues Hammer territory. This time it’s down to Wilco to save proceedings, and even if the bluegrassish ‘Joe DiMaggio’s Done It Again’ doesn’t get toes a-tappin’, the beautiful disc closer ‘Someday Some Morning Sometime’ might yet make mincemeat of expectations. The softest of piano ballads, kissed gently by electronic splashes and synth tones, it also serves to provide an unexpectedly useful signpost for what the band were up to between Summerteeth’s psych-tinged Americana and the more outré ideas behind Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. It’s worth noting that this project was the last straight-up country-rock record Wilco would be involved in for some time.

The latest instalment, of course, will be the star attraction for existing Mermaid Avenue fans. Unsurprisingly for an album composed of tracks left unreleased for fourteen years, it’s rather uneven, but there are still highlights a-plenty. Moody opener ‘Bugeye Jim’ sees Bragg complaining of an “aching brain” over some majestically bruised slide guitar – softer than the unruly entrances of the previous two sets, and a quietly engaging way to get things started. Further into the album, he also gives us the stirring anthem ‘My Thirty Thousand’ and the sonically dark, yet lyrically righteous ‘Union Prayer’. It’s all a little underwhelming compared to the previous two volumes, but still kinda nifty. Billy only really blots his copybook with passionless dirges ‘Ought To Be Satisfied Now’ and ‘Be Kind To The Boy On The Road’, which make puzzling use of an awkward falsetto. Perhaps they were originally intended to be duets with someone whose high end was a little less gnarly (Merchant, for instance…?), but either way they’re the only real duffers on the whole box set. Luckily he’s rescued by the buoyant joie de vivre of ‘Give Me A Nail’, whose feather-light hook could make the entire damn Joad family feel like Charlie Sheen if only it wasn’t over so quickly.

Wilco, meanwhile, rarely deviate from the pattern they set on previous volumes: subtle, mid-paced ballads fit snugly alongside brisk strummers that amplify the more traditional country-folk rhythms of Guthrie’s own music. The euphonium-powered oompah of ‘Ain’ta Gonna Grieve’ glimpses into the author’s spiritual side, and faint hearts will break when Tweedy gently sighs “I’m your lonesome-hearted listener / Listening to the lonesome wind that blows” several tracks later. They glimmer constantly without dazzling, but this, amongst all their contributions to are absolute winners.

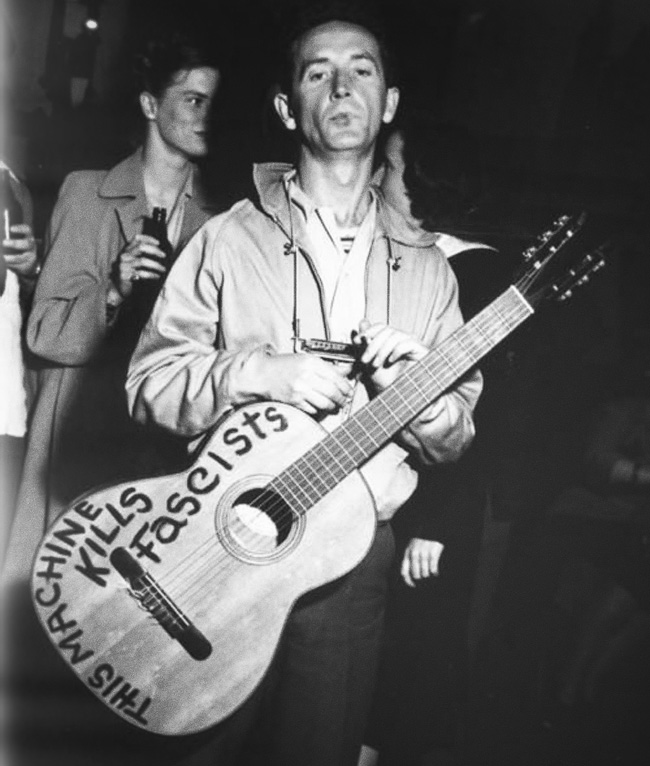

So there you go – that’s how the collaborating artists interpret Guthrie’s legacy. But what does the album tell us about the hand that wrote those lyrics? We’ve learned that he left incredible amounts of unused words behind, some pointed, some in rapturous wonder at his surroundings, and some just deliberately-silly appeals to his kids’ wavelength. But what of the man himself? Accompanying documentary Man In The Sand strives to be the key to this whole mess, and almost succeeds thanks to some heartfelt narration from Nora Guthrie herself. Endlessly proud of her father’s achievements, she tells of his time in the armed forces, sending letters home to his family because (in her words), “even falling in love was a blow against Hitler.” The anecdote is swiftly followed by an image of Guthrie holding that famours guitar emblazoned with the slogan, “THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS”, thereby setting up an important intertwining of his personal and political passions.

As with the music, the various players in the film seem to be working from different scripts. Nora simply sets out to tell the Okie folkie’s story, which she does with humilty and a notable degree of reverence. Wilco, however, have a bit part at best, whilst Bragg takes it upon himself to “search for the spirit of Woody Guthrie”, an idea so wonderfully vague that it’s no surprise he forgets to mention it much beyond the first half hour. The differences between the collaborators’ visions become apparent when the Englishman announces his ambition is for Guthrie to be regarded as “the greatest American lyrical poet” of the 20th century, discussing his politics and his directness with language. Shortly afterwards, Tweedy admits that while those aspects don’t interest him specifically, the process has made him more culturally aware of his heritage as an American. He doesn’t even appear to share Bragg’s vision of why particular tracks have to make the final cut: “I just think Woody would’ve picked the songs that didn’t suck,” he shrugs.

As you might expect of the man behind ‘Sexuality’ and ‘Never Buy The Sun’, the p-word is very definitely at the root of his plan for how the album should work. Discussing the problematic issue of sympathising with Guthrie’s worldview whilst feeling with uncomfortable with his incorrigible womanising, Bragg mentions the track ‘She Came Along To Me’. He argues that it shows his hero had “an understanding” of a feminist stance, “but like all great artists, he couldn’t keep his dick in his trousers.” At this point, an amused Natalie Merchant quips, “I don’t seem to have a problem with it.” Visibly embarrassed by his male-centric perspective, Bragg gives a wry smile and the pair laugh it off. It’s a touching moment, and made all the more clear by his later divulgence: “I realised very early on in this project that there’s no point in making excuses for Woody.”

As the documentary progresses, director Kim Hopkins seems to forget what her point was supposed to be, and the final half hour focuses on the stylistic rift that delayed the album’s release. With Bragg somewhat reticent to talk about this in depth, it’s left to Wilco to give the most concise explanation of the situation. There are a lot of “diplomatic answers”, they advise, but Tweedy affirms that all parties’ roles may not have been sufficiently clear from the outset. Bennett translates this as, “Billy and Jeff are both so fucking big-headed that it was never gonna work” – he’s joking, of course, but from his tone it’s clear that there’s a grain of truth in there somewhere too.

There are some fine live performances of songs from the project, and ‘Man In The Sand’ closes with a blistering version of ‘Hoodoo Voodoo’ that’s entirely appropriate to a documentary which fails to fully get to grips with its subject matter. Guitars blaze fiercely and Tweedy’s raw larynx squeals into life with gusto, but ultimately the gibberish lyrics make no sense. In this context, of course, the film forms part of a box set which manages to be exhilarating, disappointing, touching, underwhelming, surprising, contradictory and utterly compelling. That description may look like a confused mess, but then again what more fitting tribute can you pay to any man’s life than that? Absorb in conjunction with Woody’s own vast catalogue and cherish – as an attempt to understand the Guthrie myth, it falls short. But as a record of a fruitfully fractious collaboration between two major artists, it’s fascinating.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Emma-Jean Thackray

Weirdo

Viagra Boys

viagr aboys

William Tyler

Time Indefinite