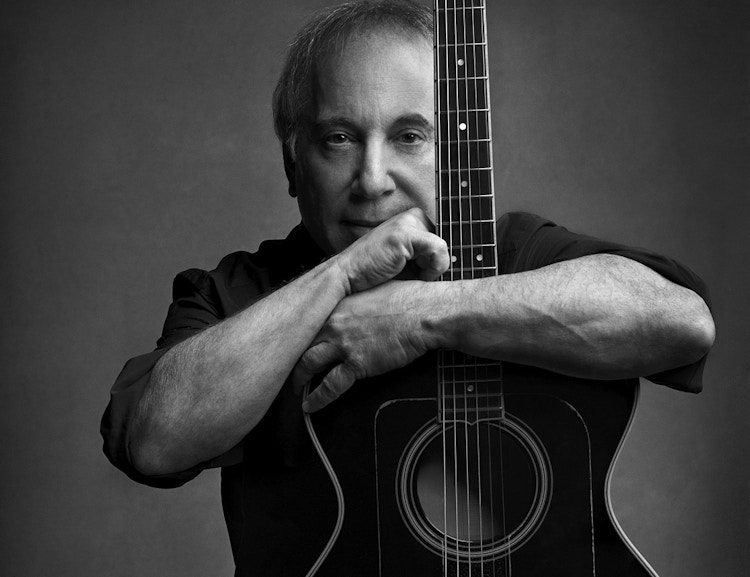

"Graceland (25th Anniversary Edition)"

“Ugh. I hate Paul Simon.”

Those were a friend’s words last weekend. An argument followed in which I indignantly defended the great (little) man; a timely debate, given the re-release of this seminal record.

It would seem that whatever will be will be reissued, and few records are so deserving of a reappraisal as Graceland. Formed in the shadow of South African apartheid, and crossing cultural picket lines by being recorded there with a host of native musicians, Paul Simon’s seventh studio album drew political revulsion from its critics and support from the UN Anti Apartheid Committee, delighted Paul Simon fans old and new, described a generation, won a Grammy, set up home in critics’ “Top 100″ lists and soundtracked innumerable childhoods. My earliest solid musical memories are a Buddy Holly cassette played endlessly on my first Walkman, and my father’s Saturday morning couch commando tendencies, regularly taking pole position on the sofa to re-watch Paul Simon’s gargantuan Central Park show. I loved Buddy, but Paul Simon’s music was something alive and real, clever and grown-up and mystifying. The seven year old me burbled the chorus to ‘I Know What I Know’ relentlessly, with little clue what the words meant. Small and naïve, I had no sense of Graceland’s cultural importance and the protests it provoked. It infiltrated my childhood so simply and solidly that I thought of Paul Simon like I thought of Paul McCartney; a fixture, a dependable presence, an uncle I surely just hadn’t met yet.

Arguably one of the most trailblazing, loved world music records ever – yet primarily, a pop record – Graceland doesn’t patronise its audience or its influences. Simon’s fascination with and respect for the rhythms and infectious sounds that drew him to Johannesburg is evident and the result is a heady, complex collection of songs. The anniversary edition includes Under African Skies, Joe Berlinger’s documentary about the recording and touring of Graceland in the dark days of South Africa’s war on its own people, with Simon returning to visit the friends he made all those years ago. As it shows, the melodic structure of this groundbreaking record was built by many hands, assembled from collaborative jam sessions and the South African musicians’ ideas and natural styles, as well as the shades of Americana that Simon was also exploring at the time, with the remarkable lyrics sewn into this tapestry after all else was done.

“Every generation throws a hero up the pop charts.”

There’s no sense of the diverse components, from mbaqanga and Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s remarkable a cappella performances, to Creole zydeco, being watered down for easy consumption; they’re already accessible, a cascade of gorgeous melodies, irresistible rhythms, voices that dance and lock together to become a complicated percussive instrument in their own right. “Our music is always regarded as third world music”, opined producer Koloi Lebona in Under African Skies, applauding Simon’s stance; his decision to bypass the concerns of the anti-apartheid movement and ignore the boycott still divides opinion, but it’s beyond doubt that Graceland did much to transport a fresh array of music styles to the mainstream and dispel tired clichés about African culture, and its influence is still keenly felt today. Ladysmith Black Mambazo became a household name after Graceland was completed, and many of the artists involved toured the record together globally.

The political story of Simon’s best-loved record provides the narrative thread to the film, but most striking is the burgeoning friendships between Simon and the musicians he approached to help him write and record the record. From initial meetings, strangers fundamentally separated by colour, language and a sediment of mistrust, to a studio full of new friends, dancing and grinning and creating something wonderful, it’s an infectious and engaging story – particularly considering the widespread misery and fear that threatened the African musicians outside the studio.

As for the record itself, it was a potent return to form for the songwriter after the disappointing flop of Hearts & Bones – the remnants of his abortive reunion project with Art Garfunkel. Graceland combined bewitching, surprising music with his trademark lyrical dexterity; he was once more at the top of his game.

“She comes back to tell me she’s gone…as if I didn’t know my own bed. As if I’d never noticed the way she brushed her hair from her forehead.”

Paul Simon is the master of the nuanced lyric, the tiny indicator that reveals the heart of the matter. As Quincy Jones notes in the documentary, “He’s got that curious mind”. A writer’s writer, his wordplay is faultless and he deploys flippancy and wit with devastating mildness. The songs skip and trill and shrug; melodies become casual little jams and riffs, phrases rolled around reflectively before revealing unmistakeable purpose. You can never accuse him of bitterness, but his observations are shot through with the loudly unspoken. After the opening four-shot explosion of ‘The Boy in The Bubble’ and Forere Motloheloa’s peerless, famed accordion groove, its expectant pace is given unsettling resonance by lines about “lasers in the jungle” and a “bomb in the baby carriage” – whether Simon is referring to Johannesburg’s troubles, Vietnam or any other upheavals of the last twenty years, the effect is arresting. Even at his most flip, there are little spots of yearning – ‘You don’t feel you could love me, but I feel you could’ – those notes reaching and clutching at human contact and understanding. And ‘Crazy Love Vol II’ is, lyrically, a painful story of a life passed by, a tragic lack of ambition, the weary using-up of time and the realisation of mortality, yet is delivered with the characteristic, smarting joy that radiates from his musical arrangements; from the opening, fluttering fall of guitars that gleam like steel drums, its bright, futile hopefulness cuts deeply.

Is the melody itself, lightfooted and flippant, a wry extension of the double-edged Jewish humour that permeates his lyrics? Or does it just serve to remind us that our problems are just distractions, the sense that even if the little things don’t work out, there are bigger things to spend one’s time on? That if the big things tank too, there’s still hope if nothing else? These are the questions that Simon’s music poses but never answers.

That eponymous, game-changing title song shuffles and chugs into view like a locomotive, before that legendary line disembarks and knocks you flat – “The Mississippi delta was shining like a national guitar/I am following the river down the highway, through the cradle of the Civil War”. Seriously, if you are one of those that really doesn’t see just what a biblical, humbling piece of songwriting this is, go back and listen to it again. Listen to the swoon of the pedal steel, bury your face in those lyrics; spare, unembellished accuracies about fatherhood, the loss of love, the search for something vital to make sense of it, the importance of faith – if not in God, in something, anything else – all mused without pomp, backed up by the Everly Brothers themselves, and carried along by that warm, elastic guitar sound that just IS Paul Simon. Go back and listen to it. Now listen to it again. Get it yet? There you go.

Early demos of some of the record’s defining moments close this edition – a nimble alternative version of ‘Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes’ and raw, revealing demos of ‘Homeless’ and that trumpet-laden triumph, ‘You Can Call Me Al’. If you own Graceland, hand it on someone who hasn’t come to it yet, and get this instead. The pleasure of this edition’s ‘the Making Of…’ themed extras make it a worthy upgrade.

Was Simon wrong to ignore all the advice and go to South Africa? That question still begs an answer which Berlinger’s film never quite provides, though it ably tells both sides of the story. If the resulting record hadn’t been Graceland, an answer might be more glibly reached. The boycott was there to isolate a racist government and show them that the world wouldn’t play ball with a nation that terrorised its black population. There’s no doubt Simon was selfish to plough ahead without seeking the approval of those who organised the cultural boycott, prizing his next record over an international movement. But Graceland is a once in a lifetime achievement, and ultimately, the magnificent end did justify the means. Great art is seldom reasonable; there is often a tyranny at work, an unshakeable belief by its creator that what they are doing must take precedence over everything else. Given what was being fought for in South Africa, it was a hell of a risk to take, but Graceland is indeed fine, great art; a rarely-matched coming together of artists, strangers of different backgrounds and languages, and an introduction to strains of music that the ruling government had sought to curb through brutal means. A quarter of a century on, Graceland still dazzles.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Great Grandpa

Patience, Moonbeam

Deafheaven

Lonely People With Power

Perfume Genius

Glory