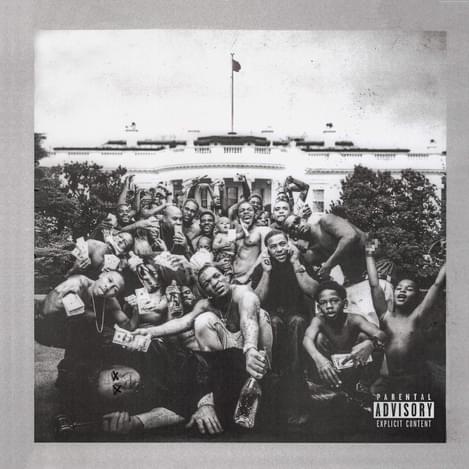

Kendrick Lamar - To Pimp A Butterfly

I’ve not been entirely kind to Kendrick Lamar lately.

After the release of the lead single “i”, a blithely upbeat guitar-based track with the repeated hook “I love myself”, I predicted that ‘Kendrick’s next album is gonna be the rap equivalent of a book with purple swirls and Buddhas on the cover called ‘Releasing The Inner YOU’’ and that it would end with ‘an extended coda featuring Jaden Smith talking about vegetables’. In the end I wasn’t entirely wrong about the coda – except it’s a conversation between Kendrick and 2Pac, built from old interview footage, and it’s human flesh being eaten, not vegetables. As for everything else, I’m happy to concede that I was wrong. After the astounding success of good kid, m.A.A.d. city, it looked for a while as if Kendrick had exhausted his repertoire of 90s gangbanging anecdotes, and now had nowhere else to go except ‘positive’ self-help banality. Turns out this wasn’t true. To Pimp a Butterfly is a rich, noir-ish contemporary take on the Faust myth, a story of depression, temptation and redemption set in hotel rooms, prisons and hospitals, all against the churning backdrop of gang wars and racial inequality in America. Nothing here is exactly what it seems; it all plays out on the scale of myth. “I don’t see Compton” Kendrick says. “I see something much worse/The land of the landmines, the Hell that’s on Earth.”

Part of the temptation he’s facing here, its most concrete manifestation, is The Industry – that old adversary of underground rappers, with its demand for formulaic saleability. Musically, this album strikes a defiant note. There are some gorgeous moments, but also far fewer pop-tune hooks or readymade club anthems than on previous releases. It’s far harder to imagine crowds chanting every line of these songs at live shows. It’s an album that sprawls; ambitious and difficult and taking up exactly as much room as it likes. Words like ‘polished’ and ‘lush’ are usually trotted out to describe the kind of production here, but they don’t really do it justice. To Pimp a Butterfly is hip-hop Baroque, full of fine fiddly rococo flourishes and sweeping operatic vastness. It’s also remarkably consistent: some tracks take their funk very seriously; others spiral away on streams of free jazz; there are even a few snare rolls on the Pharrell-produced “Alright”, some James Blake-y detuned synths at the start of “Instututionalized”, staccato electronic chants that almost sound like something from Philip Glass scattered about the album – but it still forms a strongly cohesive whole. This isn’t a collection of tracks; it’s a piece of literature.

As dazzling (and occasionally overwhelming) as the production is, in terms of sheer variety it takes a back seat to Kendrick’s voice. He’s as lyrically inventive as ever, but the real surprise comes from the malleability of his delivery. Sometimes this is driven by the music – the growling rant of “The Blacker the Berry” contrasts brilliantly with his soulful yelp on “You Ain’t Gotta Lie (Momma Said)” – but more often than not it’s driven by the story. For the great Soviet literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, texts gain their ability to speak to many people through an essential ‘heteroglossia’ – the simultaneity of different linguistic voices within a single discourse, producing what he calls a ‘dialogic’ quality. This can appear in the different speech-modes of narrative characters (as in Dickens, who do the police in different voices), but is most powerful in the ‘hybrid utterance’, where an authorial speech that at first appears as a unity is revealed to be at the nexus of a multiplicity of voices. To Pimp a Butterfly is hybrid utterance in album form. Kendrick’s star turn comes on the second interlude, “For Sale?”, in which he adopts the voice of Lucy, a mushy-voiced, sweetly seductive, almost childlike version of the Devil (Lucy=Lucifer, geddit?). “Lucy give you no worries/Lucy got million stories/About these rappers I came after when they was boring/Lucy gon fill your pockets/Lucy gon move your mama out of Compton/Inside the gigantic mansion like I promised.” This central encounter is played out against a cascade of glittering, playful melodies, and (here’s where the heteroglossia enters) for all its vocal contortions, the narrator of the track isn’t Lucy but Kendrick himself. He wants to make this deal with the devil.

How did he get here? Kendrick starts the album like Goethe’s Faust, who’s attained the peak of human wisdom and still hasn’t found satisfaction: ‘I've studied now Philosophy, and Jurisprudence, Medicine, and even, alas! Theology, from end to end, with labour keen; and here – poor fool! – with all my lore I stand, no wiser than before.’ Similarly, Kendrick Lamar’s mastery over the rap game has left him with a kind of rootless boredom. “I was gonna kill a couple rappers,” he says on the cocky, swinging “King Kunta”, “but they did it to themselves/Everybody’s suicidal, they don’t even need my help.” (There’s an even more direct parallel on “Momma”: “I know everything, I know Compton/I know street shit, I know shit that's conscious, I know everything/Not to ever forget until I realized I didn’t know shit.”) Not just boredom: the sexy, shiny disco of “These Walls” ends up framing a story of isolation and imprisonment; the injustices and inequalities that surround his sexual encounters. Meanwhile on “u” he’s suffering from full-on depression, alienated from his old friends who are dying in hospitals while he’s on tour, screaming to himself in hotel rooms and drinking alone (the drunk-voice in the second verse is something spectacular). This is when Lucy reveals herself to him with all her seductive evils.

However, unlike Goethe’s hero, Kendrick doesn’t sign the Devil’s contract. He goes back home: to his family, to a ghetto full of anger and violence, and in the middle of all this chaos he comes up with a message of black empowerment (turning the word ‘niggers’ into ‘negus’, an Amharic word for king) and personal self-belief. At least, that’s what happens on a surface reading. Closely allied to Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia is that of the ‘carnivalesque’, the joyful frenzy in which identities and truths are realised as being essentially contingent and in flux. The carnivalesque isn’t demonic, exactly, but its upturning of sacred and secular power isn’t entirely free from Lucy’s mad energy either. It’s notable that, unlike previous versions of the myth, Goethe’s Faust isn’t a tragedy: the second part, especially, is a madcap adventure in which Faust and Mephistopheles jump around through time and space, with history reconfigured as the carnival writ large. Similarly, while it addresses very serious social concerns, the second part of To Pimp a Butterfly also engages in far more play on voice and identity. There’s the fractalism of inner conflict, gang wars and political theatre on the chilling, Gothic “Hood Politics”, the interlinking hypocrisies of “The Blacker the Berry”, and then, finally, the interview with 2Pac, a reanimation that can only be read in the context of that Coachella hologram, an apotheosis of postmodern impermanence.

There’s a real darkness in this album: battles inside the mind, black bodies lying dead in the streets, the sense of someone picking for scraps through the ruins. Next to all this, the Devil is an almost comic figure. But it’s the spirit of Lucy that animates the story, with all its fractured voices and shifting perspectives. When “i” appears, the penultimate track, its central line is entirely transformed: “I love myself” – but which self? Kendrick is capable of being so many. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that he did, in the end, make his deal with the Devil. But the result is a really excellent album: uncompromising, thoughtful, and with enough buried complexities to keep people arguing for years to come.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE

Mamalarky

Hex Key

Florist

Jellywish