Frank Ocean's long-awaited second studio album is poetic, weird, complicated and quietly pertinent

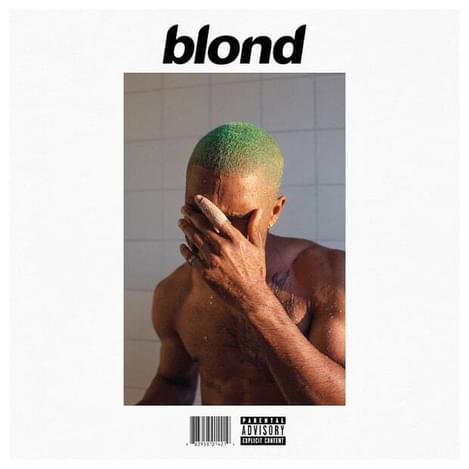

"Blonde"

The internet was awash with memes, GIFs, questions, conspiracies, and timelines fastidiously updating and voraciously over-analysing every fresh lead on where exactly Frank Ocean was, and what he was up to. Most of this proved to be either insubstantial, or flatly incorrect. We constructed the mystery for ourselves; all he had to do was vanish. He’s acutely aware of this dynamic, and the changing relationships between the consumer, product, art and artist, is a theme suspended in constant and quiet orbit around this project – which is really two projects (neither of which are called Boys Don’t Cry): Endless, the visual album and prelude, and Blonde (or Blond), the album-album. I’m not sure Frank Ocean set out to foreground these issues, but as impatience began to mount over the consistent delay of the album’s release, they became impossible for him to ignore.

On the 45-minute long visual album Endless, we watch numerous Frank Oceans stalk the interior of a large industrial warehouse as they proceed to construct – in between breaks to check a smartphone – a tall wooden spiral staircase. The staircase is effectively destroyed as he ascends to its summit (around the 38-minute mark), before Frank resumes silently building from scratch all over again. It would be easy to view the whole thing as a metaphor for the creative process (the “endless” formation, evolution, destruction and/or revision of ideas) – if the warehouse is Frankie’s brain. But it might be too easy. Endless might actually be a statement on the art of patience. Which might feel somewhat incongruous in what are unequivocally urgent times; but there’s a hell of a case for slowing down - as consumers, dreamers, creators. As people. To view the piece in its entirety - to begin to understand it, and the artist who made it - requires patient and undistracted reflection. And, it would seem that since his spectacular debut-proper Channel Orange left its indelible mark on the pop landscape, Frank Ocean’s been learning the value of these lessons, too.

Blonde is at once both complicated and understated, invoking the very best of Channel Orange and rendering it even more fragmented and porous. Channel Orange was effortlessly subtle and moving in its approach to imagery and storytelling – combining a photographic eye for detail and a close attention to minutiae (the fingertips and the lips burning from the cigarettes on "Forest Gump"; the newborn baby reaching for the nipple on "Sierra Leone") with trippy surrealism and flights of sheer fantasy (the aliens watching live from the purple matter on "Pink Matter"; the condo on the cloud in "Pilot Jones"). It was a world in which the hyper-real and the pure imaginary were collapsed into one another and remolded anew – where time slowed, and where nothing and everything was true. But Channel Orange played out in scenes and sketches – albeit delicate, incomplete ones – which we were able to step into and step out of: we’re on the roof looking out across Ladera Heights with our character in "Sweet Life"; we’re right there in the taxi at rush hour on "Bad Religion". Blonde lacks these obvious entry and exit points. They’re there, for sure, they’re just not so easy to find.

Blonde is anchored in the same closed universe as Channel Orange and, to an extent, Nostalgia-Ultra: cars, drugs, pool parties, sex, love, loss, sunsets and moonlight; characters speeding through a blurred existence, unsure of where they’re heading, finding truth and meaning in only the most ephemeral and transitory highs. We’re there from the off: "Living so the last night / Feels like a past life", he sings on the opening track "Nikes". But on Blonde our proximity to these characters and their world is magnified. Frank gets right to the surface of his subjects, right up close to the flesh. This close up it’s hard to see the entire picture; we’re so close to the image it flinches, retracts, becomes something different altogether: "The markings on your surface / Your speckled face / Flawed crystals hang from your ears / I couldn’t gauge your fears / I couldn’t relate to my peers". There’s a line of argument that says one of the problems of living in late capitalism is that it’s all empty surface-level. If anything, there’s less and less real tangible surface-level experience. We’re lost in our own bodies. Like James Blake’s (and Blake’s influence is felt all over this record – as is Frankie’s all over Blake’s, The Colour In Anything), Frank Ocean’s art often reflects and tries to work through these tensions: "Where I cannot / Where I cannot / Less morose and more present / Dwell on my gifts for a second / A moment", he sings on "Seigfried".

We drift throughout the majority of Blonde, orbiting these fragile points of contact, points that feel constantly under threat; we hover precariously over moments of indeterminacy and confusion – the feeling of not knowing how to feel, where lack and desire merge, and become the same. It’s in his style of delivery, in the way he occasionally murmurs, trips off the edge, attenuates, languishes, dissolves (see "Good Guy", or "Close to You"). And it’s there in the writing, too: "Is this the slow body / Left when I forgot to speak / So I text to speech, lesser speeds / Texas speed, yes / Eventually, eventually, yes / I only eventually, eventually, yes" ("White Ferrari"). The writing isn’t always suspended precariously at this trembling threshold, though. There are times when it boasts a brilliant photomontage-like quality – whole scenes cut with sharp details, transitioning frame by frame with a flicker, and then opening up before you. Take this, for example, from "Skyline To": "Gliding on the five / The deer run across / Kill the headlights / Pretty fucking / Underneath moonlight now / Pretty fucking / Sun rising, sand, comes a morning / Haunting us with the beams". Elsewhere, the writing feels like it's buckling under the weight of its own mad potential. Take this piece of Beckettian hopscotch from "Siegfried": "Dreaming a thought that could dream about a thought / That could think of the dreamer that thought / That could think of dreaming and getting a glimmer of God / I be dreaming a dream in a thought / That could dream about a thought / That could think of dreaming a dream".

It would be wrong to suggest, however, that Blonde plays out entirely in a state of dizzy disillusionment, or in a tangle of philosophical windings. When it needs to soar proudly, when it needs to shout, it does exactly that. Blonde is a work of supreme confidence and assurance, one that bounds assertively between genres and styles. It sounds delightful. Between the vague cracklings of sad-boy electronica – a modification of an aesthetic pioneered by the likes of Radiohead and James Blake in the UK – there are big, expansive moments of defiant pop ("Ivy") and impressive flourishes of avant-gardes soul ("Pink + White"). These are enjoyable moments, but they're not without the weight of history either, which cuts into the soft flesh of the album when you least expect. Even as we’re sliding amorphously through these melting snapshots of intimacy and desire and nakedness, the full horrors of American racism still clatter terribly and immediately into the fold. The album’s sense of sadness and alienation (and terror) takes on a whole different import and resonance in the middle of "Nikes", with Frank paying tribute to the life of Trayvon Martin, the 17-year old African American boy murdered on the walk home from his local store by George Zimmerman, in 2012. It’s a simple, devastating one line: "R.I.P. Trayvon / That nigga looked just like me". Elsewhere, the nightmares of Hurricane Katrina flash traumatically across Blonde, like unexpected forks of lightning. And when Frank sings "this is summer / Keep alive, Stay alive", on "Skyline To", it’s not hard to read as a tragic reminder that America’s hottest months are invariably its most deadly.

For an album that is at times intentionally difficult to follow - for all its vague and indistinct meanderings between subjects, between minds and bodies, between place and time, Blonde remains a highly accessible album - and not just sonically. Frank Ocean writes and delivers in a way that makes peculiar sense to those of us inheriting a world bound by so many mad contradictions and discrepancies; one that places us – the young - at its "centre", while remaining incapable of responding to our realities and our grievances. It’s as if those who were brought up living with the Internet are often presumed to have unconditionally assimilated all the manifold perplexities of digital media, past a point of no return. Which is partly true, but it’s not that simple. We’re looking for truth and goodness just like every other generation of seekers, and we’re doing our best to cling to it whenever we recognise it, however fleeting. His music speaks to these fraught and complicated urges: "It’s hell on earth and the city’s on fire / Inhale, in hell, there’s heaven", goes the hook on "Solo". But there’s also a quiet confidence underlying the uneasy melancholia that dominates Blonde, a feeling that when real change eventually comes, it’s going to be on our terms: "We’ll let you guys prophesy / We gon’ see the future first". We might be fucked up, but compared to “them” we’re doing just fine: "You’re tired of moving, your body’s aching / We could vaca, there’s places to go / Clearly, this isn’t all that there is / Can’t take what’s been given / But we’re so okay here, we’re doing fine".

Blonde is a strangely pertinent album. But it never screams its message – if you can really call it that. It’s never didactic or instructional or overbearing; importantly, it never treats its listeners as stupid. Frank Ocean shares our doubts and our anxieties – you can sense it in his writing, in its trepidation, in its ambivilance. Blonde’s not about telling us how to live (it’s decidedly ambiguous on hedonism and materialism, for example.) Rather, Blonde allows its listeners to make their own minds up, and to take what they need from it - to live. It’s this same kind of assurance – allowing the art to speak for itself, and a faith in his audience to listen and to respond - that kept him tinkering away for so long at this project in near total secrecy, until it was properly ready for release, until it was right. After all, there’s no rush. Not really. He might even disappear again soon. It shouldn’t matter to us; because Blonde is a work of art that will stick with us all for way longer than four short years.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE

Mamalarky

Hex Key

Florist

Jellywish