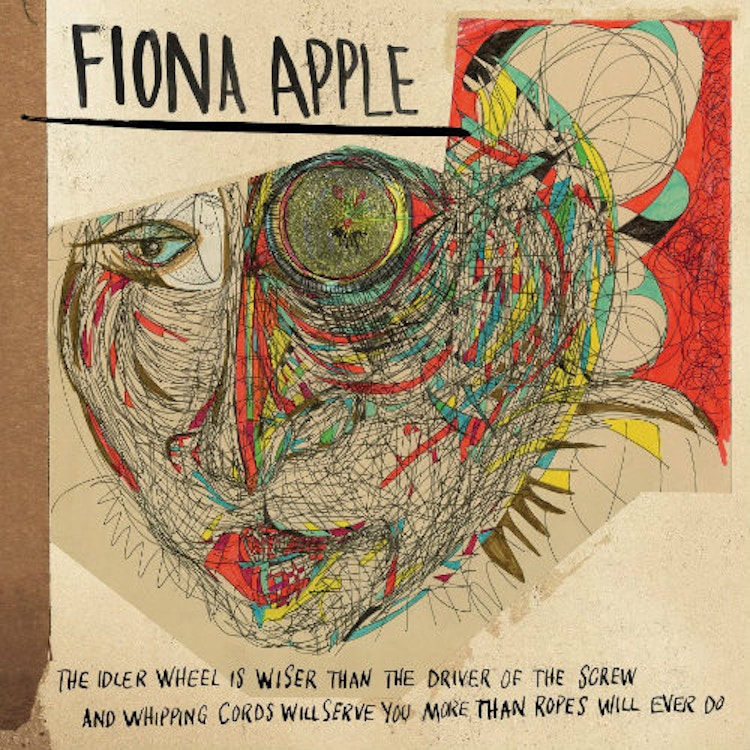

Fiona Apple – The Idler Wheel…

"The Idler Wheel..."

Fiona Apple doesn’t write music as a job or as a means of expression. Fiona Apple writes music because that’s what Fiona Apple does. Even in the realm of confessional autobiographical songwriters, Apple stands apart for how naked she allows herself to be. Apple is not the self-indulgent, self-pitying troubadour for whom music is catharsis. Songwriting is simply a way of life: if something happens to Fiona Apple and she doesn’t write a song about it, has anything really happened to Fiona Apple? Seven years have passed since Apple last laid her emotions onto the sacrificial altar with Extraordinary Machine, and while the waits can be hard on fans (it was six years between Extraordinary Machine and its predecessor When the Pawn…), it is clear that the lengthy gestation periods are entirely necessary, if only for Apple’s own sanity. Her songs are condensed sessions of psychoanalysis, in which Apple plays both the patient and the doctor. The Idler Wheel, Apple’s fourth album, is her most troubling and violent self-interrogation so far.

When Apple claims to not listen to any contemporary music, which she regularly does in interviews, she manages to do so in a way that avoids sounding haughty or dismissive. This is probably because her music genuinely sounds like it exists out of time. While her influences are clear and wide-ranging, there are no particularly indicators, other than a growing level of maturity, that Tidal was released in 1996 or The Idler Wheel in 2012. Either feels like it could have been released at any time in the past 30 years. On The Idler Wheel this is more pronounced than ever; the occasional electronic embellishments of Extraordinary Machine are gone, as are the dazzling orchestral flourishes of Jon Brion’s take on that record, leaving us with just Apple’s piano and a smattering of largely unidentifiable percussion. This lends the record an extraordinary physical quality: Apple’s piano playing at its best has always been marked by her sensuality at the keys, and here this is exaggerated in the extreme. Apple is often confused for a primarily lyrical musician, but that does a strong disservice to the complexity of her compositions. Her use of the piano as a physical instrument is unparalleled in popular music, owing more in terms of influence to Lazar Berman or Daniel Barenboim than any of her direct contemporaries. Every note is delivered with a deftness and directness, but this isn’t a case of mistaking hitting things hard with emotional playing. Indeed, for a record so liberally littered with emotionally bruising lyrics, musically it is surprisingly restrained, on the part of both Apple herself and percussionist Charley Drayton. Drayton offers a lesson in intelligent drumming, opening up every song with just the amount of momentum it needs, muscular in places and delicate in others, illustrating lyrics like “I don’t feel anything til I smash it up” with a show-don’t-tell philosophy.

Rarely is anything worked out over the course of a Fiona Apple song, and rarely is there a triumphant moment of epiphany. If anything, things are often made worse: “There’s nothing wrong when a song ends in a minor key”, goes the already oft-quoted refrain from ‘Werewolf’. So often we catch Apple in the act of pure self-flagellation, with a line like “How can I ask anyone to love me/When all I do is beg to be left alone?” emblematic of her attempted analysis of her own psychosis. Apple spends the last two minutes of ‘Regret’ shredding her throat with guttural screams of “leave me alone”, in one of the few moments of the whole album where the aforementioned restraint is lost entirely. Apple claims that “Every night’s a fight with my brain” on the album’s opening track, and the rest of the album surely lives up to this claim, but it is only on ‘Regret’ that we feel like we’re hearing that fight reach a climax. There are points when this is positively uncomfortable, and there are moments when it is deliberately ugly. Eschewing popular music’s obsession with the beautiful and turning our heads towards the darker side of human emotion has always been Apple’s raison d’être. Most singers have a way of making the pain of heartbreak sound beautiful and romantic. Apple makes it sound excrutiating.

It is hard not to feel voyeuristic, bordering on the sadistic, as we listen to Apple tear herself apart. In interviews, she often seems over keen to push the fact that her songs are autobiographical, but it is an important point to stress. Employed as metaphor or as fiction, a line like “While you were watching someone else/I stared at you and cut myself”, from ‘Valentine’, is trite and exploitative. As autobiography it is transcendent and visceral. There is a passage in Milan Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting when the author confesses to feeling “a violent desire to rape” a friend of his. It’s a horrifying moment in the novel because it is clearly flagged as autobiography, which not only lends it a terrible weight, but also removes the comforting veneer of fiction that would allow us to see the confession as a literary device, a psychological piece of character development. Once we know we are hearing a genuine confession, there is no escape and nothing to hide behind. Kundera once described himself as “a hedonist trapped in a world politicised in the extreme”, and it is not too difficult to imagine Apple sympathising with this. Apple is a hedonist in as far as she feels everything in its purest form, she is thrilled by the pursuit of raw emotions, of lows as well as highs. On ‘Every Single Night’ she sings: “I just wanna feel everything”. Regardless of the level of metaphor she employs, it is clear that the emotion behind it was felt truthfully. Fiona Apple is a liver of life, and like Kundera, for better or worse, she chronicles that life with unflinching honesty.

One of my favourite lines of criticism comes unsurprisingly from Roger Ebert, on the subject of Sofia Coppola’s Lost In Translation. The film’s two lead characters, Ebert wrote, “share something as personal as their feelings rather than something as generic as their genitals”. I love Fiona Apple’s music because, whether it is ugly or beautiful, she is determined to shun the generic and share with us something personal. Never has that been truer than on The Idler Wheel.

Listen to The Idler Wheel…

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex