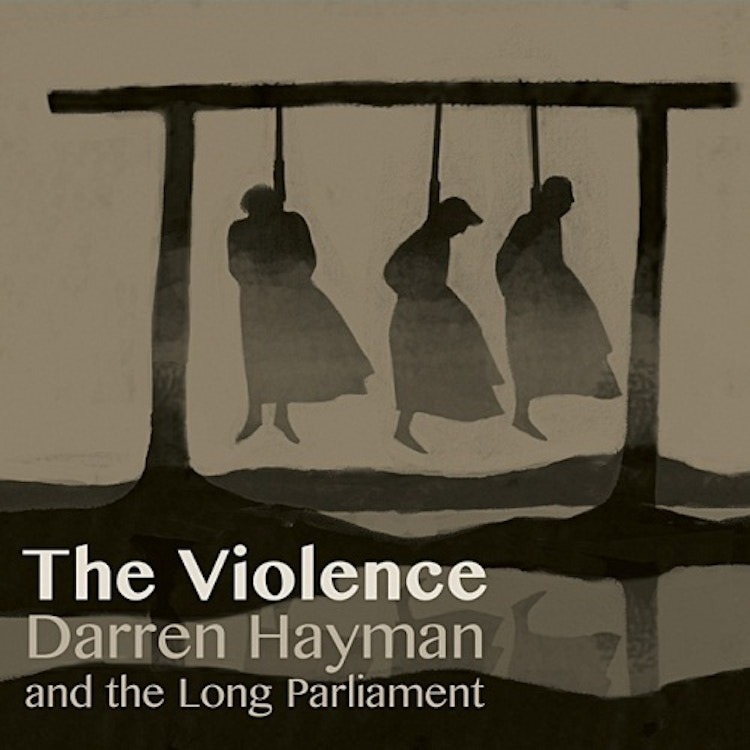

Darren Hayman and The Long Parliament – The Violence

"The Violence"

An album about Essex. In the hands of Darren Hayman this isn’t the Essex that the media would love us to believe defines itself through fake tan and makes its historical mark via the consumption of jagerbombs. Further distance from the usual is negotiated by the transposing of Hayman’s perceptive tales of social incongruence and sexual transgression, like a barred chord shape pushed further down the guitar neck, to the Essex of the Civil War and Witch Trials of the 17th century.

Sounds like heavy going? It is. But who doesn’t prefer The Sorrow and The Pity to a Channel 5 documentary about people born with dog’s cocks? Never mind. The point is that this 20 track musical dissertation is long but finely textured, offering a degree of depth and insight to a modern pop record that is as rare as its multiple narrator approach; dancing between the first and third person, between executioner and persecuted, between male and female, royalty and peasantry.

The album’s varying approaches to the politics of the time and the religious issues that smothered England during the era can seem confused but are often beautifully phrased as on ‘How Long Have You Been Frightened For’ with its erotically charged description of the eschewing of formalised worship “No stained glass windows to block sunshine/No effigies or idols, no red wine/To bind me to the ground”.

When we are given the point of view of Matthew Hopkins’ followers (Hayman generally keeps his voice in the mouths of those not in charge, those whose lives are being twisted by the world around them – as he does for the most part on his regular, non historical-witch-trial albums) – we get the Wicker Man harmonies of ‘We Are Not Evil’: an ominous beast that tells us “We can smell the devil hiding in the towns” then offers, by way of justification to society, “Someone’s got to guard you”. It’s a tender marching song that presents its blinkered case with conviction. Hayman seems to be implying that everyone on every side believes they are doing the right thing.

Never feeling purposely epic is one of the more admirable traits of the record. Certainly Hayman gets mired in his subject matter – there are several instrumentals that are understandably dotted around in order to bed us in to the atmosphere or perhaps even act as respite from the relentlessly bleak subject matter but that often seem superfluous. Also the referential nature of much of the material will have you diving for your nearest book on the Civil War as names like ‘Henrietta Maria’ (Charles the First’s resilient Catholic wife), ‘Parliament Joan’ and ‘Vinegar Tom’ are tossed out quite casually, potentially deterring the more casual listener.

Luckily Hayman deploys the sneaky strategy of being a Very Good Songwriter to avoid the listener’s potential alienation – even though these are songs about the 17th century they are not of them. The emotions and ideas expressed here are entirely relatable.

Album highlight ‘Elizabeth Clarke’ for instance describes the fate of the very first woman accused of, and executed for maleficium by Hopkins and expresses her woe in simple, pitch-black nursery rhyme tones: “Who’s going to feed my dog?/Who’s going to pray the rain away?/Who’s going to pull on my ankles when I swing?”. It’s breathtakingly sad but bravely sung, a tale of inevitable endings of which that we can all understand something.

The instrumentation here is relatively minimal – aside from the occasional horn we stay largely acoustic except for the rolling organ of ‘A Dogge Called Boye’ and the reversed vocal loops of ‘Rebecca West’ (which, incidentally is home to one of the great lyrics of the album: “ Ten different devils came knocking at your door/And you, you dizzy whore/You let them all in” as well as one of the more satisfying melodies), giving an idea of agelessness on a record that is very much about understanding the past through its relationship to our emotional present.

Certainly as we enter the home straight the record begins to feel a heavier load to carry – by the time tracks like the ‘Arthur Wilson’s Reverie’ and the baying ‘Kill The King’ roll around there’s a fair chance you’ll be unwilling to listen to much more in the way of weighty, sorrowful and overtly literate laments. Closer ‘The Laughing Tree’ is a black bow that wraps the record neatly, ensuring that we’ve understood the stresses on the immensely personal tragedies that befell so many: “With the root ‘round my feet and dirt in my mouth/There’s nothing much here to laugh about”.

The Violence is a bold record – sometimes muddled, occasionally baffling but for the most part affecting, impressively assembled and ultimately enlightening. More like a great read than a standard pop record it benefits from listening in chapters with perhaps occasional diversions to the history books for context before continuing with the carefully collaged tale. It asks a lot, offers a lot and leaves you richer for the experience. You can’t say that about any other concept albums about 17th Century Essex now, can you?

Listen to The Violence

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Wet Leg

moisturizer

MF Tomlinson

Die To Wake Up From A Dream

BIG SPECIAL

National Average