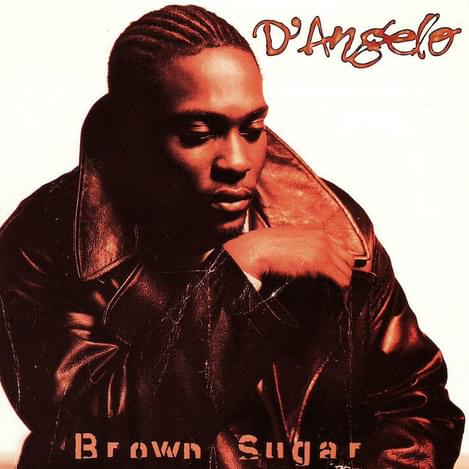

D'Angelo's Brown Sugar remains a minimalist masterpiece, twenty years on

"Brown Sugar [Reissue]"

D’Angelo is a model student, in that regard. He wasn’t classically trained. The upscale likes of Juilliard were a long way removed, in more ways than one, from his hometown of Richmond, Virginia, but it was there that the very first seeds were sown for this record; between his mother, a huge jazz aficionado, and his father, a Pentecostal minister, he was handed a solid grounding in jazz and gospel, whilst his own tastes drove him towards soul, classic R&B, and hip hop. He taught himself to play the piano, becoming proficient enough by the age of eighteen to wow record executives with an three-hour recital off-the-cuff. By the time he came to write Brown Sugar, primarily in 1991 and 1992, he was already looking like a virtuoso, skilled enough in guitar, bass, drums, saxophone and keyboards to take on the album’s instrumentation pretty much single-handedly. Even the hardest of cynics would struggle not to see the poetry in the fact that he paid for the four-track he used to demo the material with money won at a talent competition at Harlem’s legendary Apollo Theater; as far as his rise to stardom was concerned, it’s difficult to shake the feeling that the script was written well in advance.

What’s remarkable about Brown Sugar is that it doesn’t fall prey to either of the likely fates for a solo record that draws on so many influences and was born of such a range of instrumental ability; it feels neither disparate nor like a kitchen sink job. In fact, on the contrary; Brown Sugar is masterfully restrained, an exercise in tasteful minimalism. The rhythm section drives the record, yet rarely seems to amount to much more than the crackle of the snare and a wandering bassline. The piano lines are unobtrusive, yet crucial; on the jazzier tracks - “Smooth” and “When We Get By”, for instance - they almost seem independent of the song, running parallel to it rather than feeling part of it. The guitar is used almost entirely for punctuation, but when it is - on “Alright” and “Me and Those Dreamin’ Eyes of Mine”, especially - it’s indispensable.

There’s early evidence, too, of D’Angelo’s flirtations with classical arrangements; the string section on that now-classic cover of Smokey Robinson’s “Cruisin’” is a masterstroke. In the larger scheme of the record, it was just another factor setting D’Angelo apart from the rest of the mainstream R&B world in the mid-nineties. At that point, the transition in the very meaning of that tag - from the rhythm and blues classicism that it actually stood for to where it stands today, effectively as a byword for urban-inflected pop music - was already underway, and in 1995, when the likes of Jodeci and Brandy had one eye on the charts, D’Angelo was continuing to fly the flag for purism - that he still managed to deliver something startlingly original in doing so is testament to his ability as a songwriter.

Also distinguishing him from his peers was his lyricism, which, on Brown Sugar, largely felt like a throwback to classic soul; this is an album replete with love songs, making it far and away his least complex album in conceptual terms. There’s nothing wrong with that, by any means; if you’re going to delve into straightforward balladry, then at least take your cues from the old maestros. Stevie Wonder’s presence is palpable on “Dreamin’ Eyes”, “Smooth” and “Alright”, whilst the spiritual leanings of “Higher” are a direct thematic nod to D’Angelo’s gospel roots. That he still found room for a chillingly sedate murder ballad - “Shit, Damn, Motherfucker” - and the nudge-wink of the title track, an ode to good weed rather than women, is impressive in itself.

And then, there’s that voice - and something else that has you realising what a one-off the man is. So much of a soul singer’s force of personality is wrapped up in their vocal delivery, so for D’Angelo - who by no means is a slouch in that department, with a readily recognisable falsetto - to pare back the importance of the vocals in the overall mix - to treat them as just another instrument, and to apply to them the same principles of minimalism as he does to every other area of Brown Sugar’s compositions - was a maverick move. He pitches his vocal approach somewhere between the soul that pervades the album’s instrumentation and the languidness that his hip hop heroes could lay claim to. His voice might sound smooth throughout the album, but his actual delivery was often not - there’s an offbeat confidence to his refusal to be bound by conventional standards of where the vocals should sit in relation to the rest of the track, something he probably owes as much to his jazz influences as to his admiration of Rakim or A Tribe Called Quest.

This new vinyl reissue is no remaster, and with just reason; there’s nothing wrong with the original. It’s all too easy to romanticise analog recording and the vinyl format itself in this day and age, but Brown Sugar provides compelling reason to feel nostalgic about both; it’s difficult to imagine how an album this sparse could still feel so warm if it had been digitally recorded, rather than cut to tape. Long since out of print on wax, this repress will allow a new generation to hear such a crisply captured R&B album the way it was intended. More than that, though - two decades on from its release - it provides an excuse, if anybody needed one, to revisit a game-changing classic of the genre, and in doing so, allow it to step out of the shadow cast by Voodoo and, more recently, Black Messiah.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Great Grandpa

Patience, Moonbeam

Deafheaven

Lonely People With Power

Perfume Genius

Glory