Bob Dylan remains an immeasurable and inimitable force

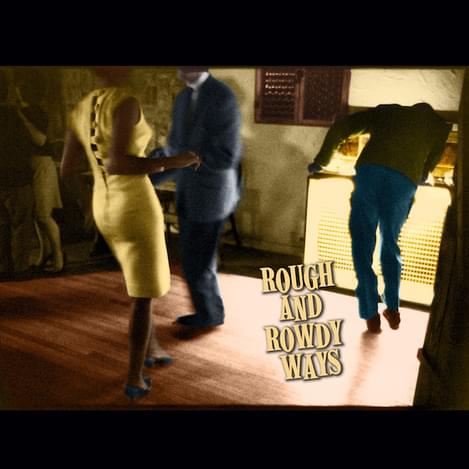

"Rough and Rowdy Ways"

Look close enough, and you’ll know him better than you’ve ever known anything in your life – but the more you look, the more you find. ‘Bob Dylan’ has not meant the same thing to anybody, or anyone, since at least 1965 – and people born that year could ostensibly be great-grandparents in the next few years. He is elusive, amorphous, a ghost – he is both a prophet and a bum, a fraud and a god, a wise old man and a newborn phoenix shaking ash from its beak. He’s been letting people down since he first plugged in an electric guitar, and he’s been thrilling them since he first dipped a harmonica in a glass of water in a studio session with Harry Belafonte.

Like Shakespeare, the folks that wrote the Bible, and whoever wrote the U.S. Constitution, Bob Dylan’s words have been pored over, reinterpreted, ignored, taken as gospel, rephrased, reimagined and plagiarised so many times that trying to find out the length and breadth of the influence of just one of his albums on modern society would be an impossible task. Bob Dylan is immeasurable, both the unstoppable force and the immovable object. Bob Dylan just is.

As for Bob Dylan albums, because there are just so many of them, and so many fantastic ones, they are most easily categorized by comparison to others in his own canon – long gone are the times where you might compare a Bob Dylan album to anybody else. So let’s start, in earnest, by saying that Rough and Rowdy Ways is in the gold star, A1 prime album category. His most recent album, Triplicate? It’s better than that. His most recent album of original material, Tempest? It’s better than that (although that still remains one of his most fascinating records, and one of my personal favourites). Make no mistake - you’d have to go all the way back to 1976’s Desire to find an album as diverse and bewilderingly impressive as Rough and Rowdy Ways. And here’s why:

The most famous lyricist in the history of song, Dylan presents us with ten glorious songs, and each of them is a puzzle. Across the entire record, the words are as tempting and as cryptic as their accompanying tunes are easy and supple. He is the master of adaptation, and always has been: as his music has grown simpler, and his basic palette has become earthier, his lyrics have become denser, and each simile he casually throws out into the world is a riddle. Umberto Eco once described James Joyce, with Finnegans Wake, as having “prepared a machinery of suggestion, which like any complex machine, is capable of operating beyond the original intent of its creator” – and Bob Dylan’s songs here on Rough and Rowdy Ways do this and more.

Bob Dylan appears, with each passing year, to have digested more of the very fabric of human history than any prophet or sage before him. When Dylan mentions “Crossing the Rubicon”, on the strutting blues number of the same name, we’re left unsure as to whether he means Robert Zimmerman crossed the Rubicon river in Italy, or whether he has become Julius Caesar crossing the river in 49BC, or both, or neither. He could actually mean that he’s enjoyed a can of the sparkling soft drink with some wings from his local SFC. We simply do not know what he means, and part of the fun of a Bob Dylan album is attempting to figure the riddles out.

Dylan acknowledges this, and indeed considers his entire legacy, on the opening track “I Contain Multitudes”. He uses his endless stream of similes to compare himself to those British “bad boys” The Rolling Stones, joke about William Blake, reference Edgar Allan Poe, Anne Frank and Indiana Jones – and even finds time to wink at David Bowie.

“My Own Version of You” is a grotesque retelling of the Frankenstein story, with Dylan pining for his lost love via Shakespeare references, death wishes and hilarious rhymes: “I’ll take the Scarface Pacino and the Godfather Brando / Mix ‘em up in a tank and get a robot commando”. The lyrics play out like Muhammad Ali’s casual poetic boasts, and Dylan (we know that all of his narrators are him by this stage), seems to be having a lot of fun talking about Leon Russell, Liberace and St. John the Apostle. Why not?

The rough and rowdiness of the title is completely embodied by “False Prophet”, the second cut on the first disc. The gleaming golden guitars evoke both The Rolling Stones and The Velvet Underground, and the simplicity of the thunderous percussion emphasises the primal pleasures of such a dirty blues. “I’m first among equals, second to none/The last of the best, you can bury the rest”, Dylan spits – with enough conviction that you believe he believes it. “Goodbye Jimmy Reed” (he’s been dead 44 years) also summons a gutsy, muscular blues groove and sets Dylan’s voice on top of a hulking strut – anybody else hearing echoes of The Basement Tapes here?

Dylan immediately soothes the burn with “Mother of Muses”, which is a spare, hymnal ballad. Dylan’s voice is earnest and sincere, and pleasingly evokes a sunrise in the middle of Spring. When he casually sings about Elvis and Martin Luther King, it’s as though he’s talking about old friends that he wishes you’d had chance to meet. “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You” occupies much of the same space – a hauntingly emotional paean to a lover, to God, to love itself. Brushed drums, a subdued backing vocal accompaniment and chiming guitars – Dylan conjures the version of himself so beloved by David Lynch, the spare and magical preacher who converts by platitudes and dedications rather than threats and warnings. It evokes the sincere solemnity of his gospel years, and the subdued strength of his most recent albums.

“Black Rider” is a campfire, wild frontier tale told in the dead of night, like an anecdote told by one of the horsemen in Blood Meridian, and “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is a sepia-tinged yarn that could have been drawn up by Truman Capote or Jack Kerouac (who gets a mention) on a particularly sunny evening. It carries with it an ominous, doom-laden sense of foreboding that makes it sound inviting yet thoroughly disorientating - it’s got a woozy, seasick, headrush dizziness that doesn’t happen by accident.

If “Pay in Blood” (from Tempest) was his Titus Andronicus, then “Murder Most Foul” is his Macbeth – his foulest, bloodiest tragedy to date. Occupying the whole second disc, “Murder Most Foul” runs to 17 minutes and not a single second or word is wasted. It is already iconic, a modern classic as soon as it left his head – doctorate theses are already being written about it, God is already on his thousandth play. The lyrics, which seem to cover the entire recorded history of popular culture since Dylan himself entered it in 1963, are heartbreaking in their unabashed horror, with Dylan musing on the carelessness of humanity and the impermanence of time. It is an opera, a Proustian exercise in attempting to capture the essence of the winds of change. Etta James, Marilyn Monroe, The Eagles, Wolfman Jack, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Bugsy Siegel, Pretty Boy Floyd, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, Nat King Cole, Lady Macbeth, Debussy… This is the story of Bob Dylan’s life, told via the shocking murder of the Leader of the Free World – only this is the story of ‘Bob Dylan’ the singer, the icon, the iconoclast, the enigma, the voice of the voiceless and the traitor of the very same. Through Bob Dylan’s own words, ‘Bob Dylan’ becomes the cypher through which to view the downfall of modern society. If the President isn’t safe, he asks, then who are we to presume that we are? If the life of John F. Kennedy was so easily expunged and his legacy pulled up by the roots, then who are we to think that we have any impact on the world?

When asked if his last album of originals, Tempest, was named thus as a reference to Shakespeare’s last play, Dylan spikily responded that the play “wasn't called just plain Tempest. The name of my record is just plain Tempest. It's two different titles.” He was right, of course, both literally and figuratively – Rough and Rowdy Ways has far more in common with Shakespeare’s final masterpiece than the similarly-named LP ever could.

Rough and Rowdy Ways is a magical, threatening and ultimately challenging metaphysical exhibition of a writer’s limitless talent riding roughshod over convention. This album is relaxing yet jagged, biting yet withering, loving and distant – like a violent, romantic thug who can only show love when their back is against the wall. Perhaps Dylan says it best when he says he’s a “man of contradictions”, and a “man of many moods”… Or maybe Shakespeare has it right – perhaps music’s very own Prospero is now, finally, ready to abjure his rough magic, break his staff and bury it certain fathoms in the earth. Or maybe he’s not. This is Dylan at his most open, most sincere, most giving. He knows exactly what his listeners want (he always has), and now he gives it to them in spades. Rough and Rowdy Ways is long, intricately woven and illuminating as a medieval tapestry, and just as precious. It’ll make you cry, it’ll make you tear your hair out, it’ll make you gasp with awe.

In the wildest year that many of us have ever lived through, it’s no surprise that Bob Dylan is our guide, our constant, our prophet – the truest chronicler of human experience ever born and the most frustrating author ever to put pen to paper. Each lyric hides an endless series of fragmented meanings, each syllable a shard of cultural experience both ancient and modern.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Prima Queen

The Prize

Femi Kuti

Journey Through Life

Sunflower Bean

Mortal Primetime