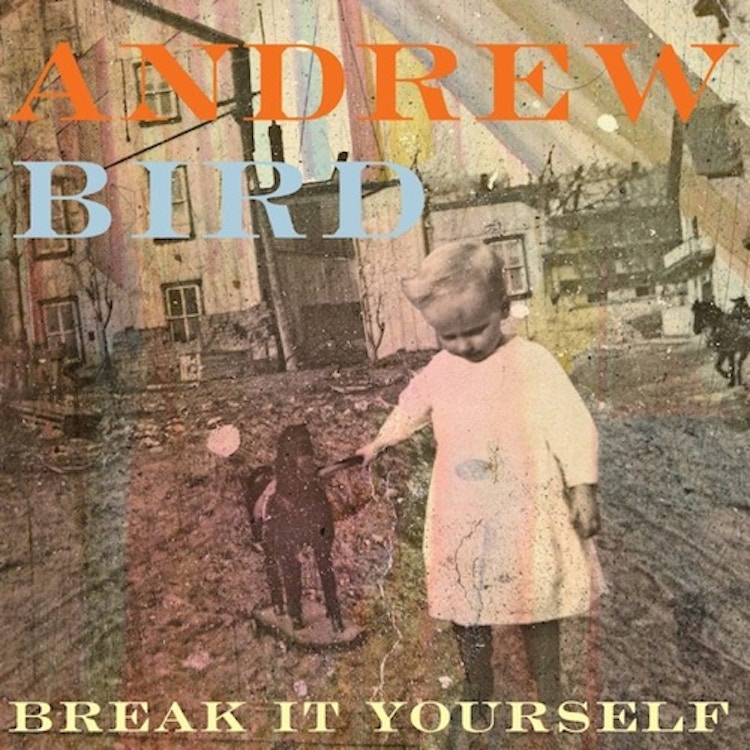

"Break It Yourself"

There have always been great artists in the world who have gone largely unrecognised, remaining as minor footnotes to popular music as they grind away, fashioning masterful works that barely register as an irregular blip on the simplistic radar of popular consciousness. Talents like Paul Westerberg in the ’80s, Mark Kozelek in the ’90s and now, unless there’s something of a seachange in the intellect and emotional understanding of the general public, Andrew Bird in the whatever-you-are-meant-to-call-these-ys. Not that Bird is similar musically to Westerberg or Kozelek – very, very far from it. Perhaps the largest looming “missed” talent he could be said to shadow is the most often cited example of overdue musical attention in history, Nick Drake (but with a violin, like); but he certainly shares with these oft-disregarded names a knack for writing astonishing music that no-one gives a fuck about in the grand scheme of things.

His new album Break It Yourself is the richest, most addictive record he’s made since starting out in 1996; an intelligent, perceptive, extremely well-judged pace across welcoming shores of emotive, articulate pop music writ large with the innate power and exoticism of classical instrumentation.

Whether Bird is recalling the shrugging, street-strolling strut of ’70s Paul Simon on delicacies like ‘Orpheo Looks Back’ (which despite its tuneful appeal gravitates magnificently to a grandiose excursion into stringed experimentation), or dropping Go-Betweensy goodness on the swaggering, classy wink of ‘Near Death Experience’ (which opens with the jaw-to-the-floor wonder of the lyric “You used to be like toffee/Between a kitten’s teeth”, and somehow swings through its purposely obtuse chorus of “We’ll dance like cancer survivors/That feel grateful simply to be alive”, which in less graceful hands would of course come off, well, horribly) he’s consistently aware of sound, word and structure, and the effect that the trinity have not only on the listener but also reflectively, within the song itself.

‘Danse Caribe’, for instance, presents an utterly irresistible dramatic pop blueprint – but instead of dropping and crashing in where lesser talents would simply find it too hard to resist, the song pauses, restrains itself and delivers shivers instead of clenched-fist thrills. The liquid swell of the chorus - “Here we go mistaking clouds for mountains/Here’s the thing that brings the sparrows to the fountains” – refuses to punch where it should, tickling instead; a tease between the song, artist and audience that leaves all three ready to roll into the whistling afropop changes that ring in moments later, into a full reel that reveals a shy, near-gothic heart at the centre of this swirl of song.

The charmed invention continues through a selection of other ideal-world hits like ‘Give It Away’ (surprisingly not a Chili Peppers cover – so disappointing), a wry, searching lover of a song which is genuinely clever in its observations (“What about appreciation?/That depends on your depth and density”) but never bloodless – its “Nation under your command” payoff refrain a tiny wonder in itself. Again there’s a little three-way transaction occurring between Bird, the song and the listener: once we’re immersed in the comfort of the track’s shape, getting to know its edges and parameters, he nudges us into a time change that we first shy away from but then quickly see the wonder of, as if Bird is a guide into the complexities of his own music.

‘EyeOnEye’ opens with Bird spitting the word “snakebit”, then unfurls into the kind of awesome indie pop song that would, were Morrissey still be capable of anything close to this level of intuition and purity, see the bequiffed one re-installed in hearts across the world. Even though there’s actually some whistling in it. It’s the most driving, blatant tune on the record but again refuses to show its hand in any way that could be considered conventional – even if the thrum of a rarely-prominent indie geetar is a strange and welcome sound among the strings that dominate the landscape of the rest of the album.

There’s no doubt of course that Bird still remains very much a classical composer, and on tracks like ‘Things Behind The Barn’, the brief ‘Polynation’ and the filmlike ‘Last Song’, an evocative cry of need both ambient and ambivalent, he flaunts his chops a little without alienating those used to his more “conventional” songs, just showing another facet, another aspect of the whole with a nod and a “have a little listen to this”.

There may be the odd drift into repetition, ‘Lusitania’ for instance just sounding like a.n other song in the collection, and on opener ‘Desperation Breeds’ a little too much of the baroque near-jazz that Bird can sometimes lose himself in, but this is balanced mightily by another clutch of stunners including ‘Hole In the Ocean Floor’ a lengthy, near-weird Buckley romp and its watery sister ‘Fatal Shore’, a torch song with a guitar that glimmers like a dress falling to the floor.

‘Lazy Projector’ and ‘Sifters’ are the most moving inclusions here; the former a sweet damning of memory – “That forgetting, embellishing, lying machine” – which plays cousin to the upper echelons of the works of Grant McLennan, the latter carrying a set of lyrics so tear-inducingly open, well-observed and worldly that it’s best not to regale you with them here. You can hear them when you buy the record.

As unrecognised as Bird may continue to be, and let’s hope that’s not the case as time goes on, we can at least say that he is a tremendous, stellar success in the only realm that truly matters – the creation of great, timeless art that touches both the head and the heart, taking residency in both.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex