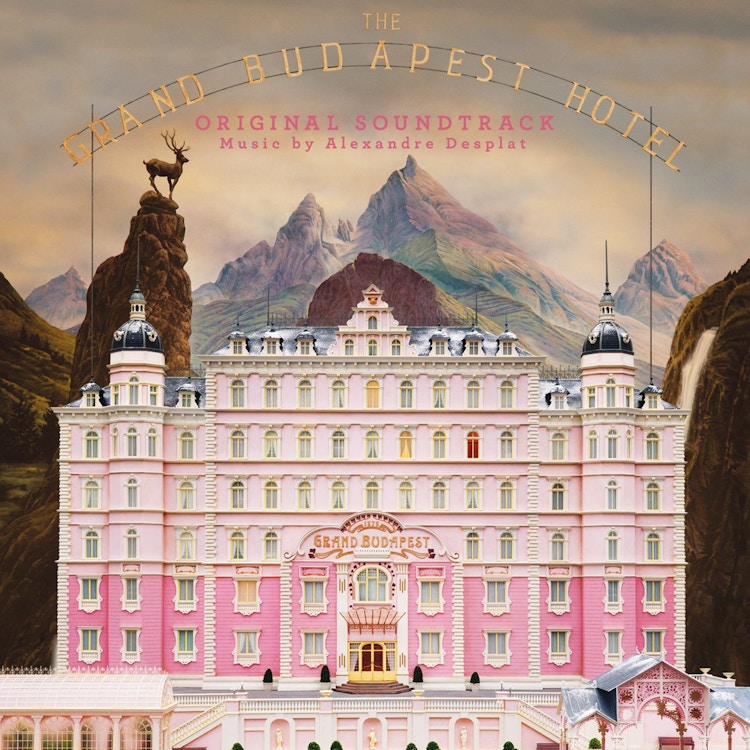

Alexandre Desplat – Grand Budapest Hotel OST

"Grand Budapest Hotel OST"

It’s surprising how few people take the time to listen to movie scores, but if you’re going to take the plunge then Alexandre Desplat is a great place to start. His music is untainted whimsy, first noticed on his score for Extremely Loud And Incredibly Close which told the story of a child discovering a city and the people within it. That film and Desplat were a perfect match as the sense of wonder he demonstrates, with all its curiousness and naivety, go very well with an inquisitive child’s viewpoint of an endless cityscape.

Here’s the thing though; is that what the music actually makes you feel, or are you swayed by the film itself? It’s an interesting suggestion that instrumental soundtracks can’t exist on their own, being brought to life with a purpose to backdrop visuals, catering for what’s already there on screen, rather than forming its own narrative. Let’s look at the Grand Budapest Hotel OST on its own then, without the film for reference.

The first thing that grabs you is that capricious quirkiness again. The piano line on “Mr Moustafa” is playful, making it’s own way through the progression against the intensifying grain of the rest of the string section, which feels worried and attention seeking. That agitated tension continues on the brief “Overture: M Gustav H” before the keys, assumedly the main character on this record, jumps back in to guide the rest of the performers into action. Over the next few minutes the sound begins to explore its surroundings more; the animated Eastern European dancing of “The New Lobby Boy” and “Concerto For Lute” that demonstrates the opulent establishment of the subjects’ positioning. It’s showy, mirroring obvious classical influences with intent to prove a point. By keeping things light and technical, Desplat can make such comments while the likes of Hans Zimmer push attention to emotion, or drama, creating less engagement with the audience, if admittedly more impact.

It’s the piano melody that makes the boldest assertions throughout, always pushing a bit harder, the rest of the orchestra merely catching up or opposing it, even in the case of “Last Will And Testament” that creaks with tragic spectacle. At it’s sprightlier times, where more avenues are visited by jangly twangs on triangles, such as on “The Lutz Police Malitia”, you can get underwhelmed by the record all too easily – in a good way though. These quieter moments allow you to sink into the Grand Budapest Hotel, and not only is that exactly what you do, but it’s what you should do. Going back to that idea of a score having it’s own sense of identity, the second you slip underneath one and begin daydreaming you know it’s worked. Once your mind wonders, the real joy of listening to albums like this becomes apparent. You make it up as you go along – incorporating those little things you noticed from the start, which now dance boldly around in full colour playing out all sorts of wonderful amusements. By “Private Inquiry Agent” the world crafted by Desplat is almost fully realized, or enough anyway to take note of and slip further away with.

From there the album is what you make of it yourself. These songs aren’t really “about” anything in the modern sense – they’re meant to inspire something in you, and with his delicate approach Desplat gets that reaction. It’s music to travel with, or work to, or daydream over, and makes a change from the usual classical albums that one may turn to in such circumstances. For the most part, this is what classical music is now and deserves more appreciation than it gets for being so. It’s a wonderfully written, dynamic work that spring to life if you let it, impressed with a completely modern brush, from “The Society Of The Cross Keys” and “M Ivan” that borrow from the pop world, to “Kamarinskaya”’s mindboggling complexity. Give it a try – then listen to Zimmer’s Inception OST for comparison.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday