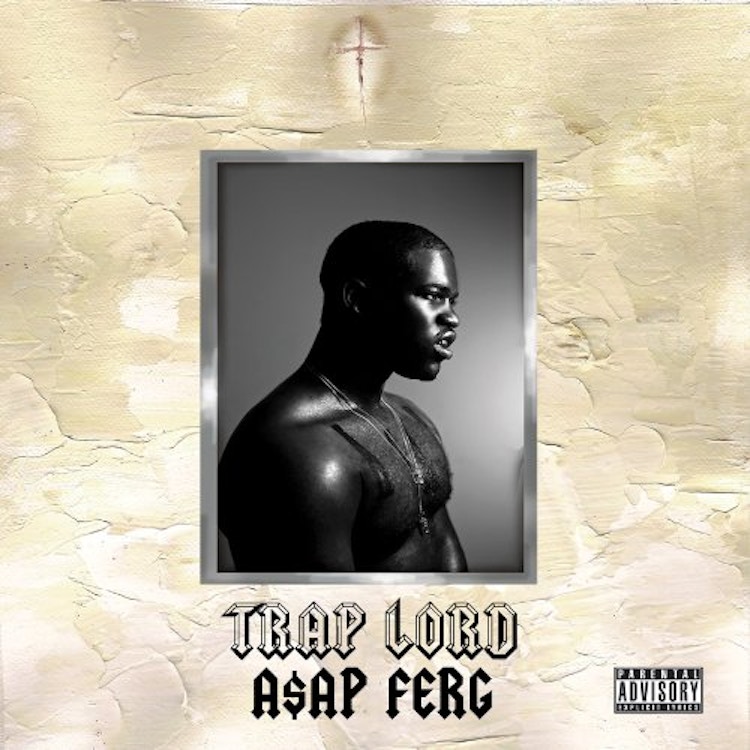

"Trap Lord"

There have always been rappers, on the peripheries of greatness, that forever will be best suited to crew cuts, where they can come barrelling down from the wings, notebooks unbound and best bars brandished, sometimes flying with their more talented peers, sometimes flailing, always desperately trying, and in any and all cases enhancing the clique’s generals, by addition or by subtraction (or occasionally by division). Many of these bit players, these lesser celestial bodies orbiting around – and lost in the corona of – rap stars, are bound to these tedious ellipses by their own failings; something about them, their voice, their lyrical content, their beat selection, their presence, holds them back and, unable to shake the albatross in the brutal meritocracy that is rap, instead continue on their seemingly destined journey, cropping up now and again in forms both beautiful and graphic, Venusian reminders that there are more planets than stars.

More tragic than the moderately gifted are the rappers who were never allowed to flourish, who found themselves caught up in the machinery of the record industry, rappers who simply forever simmered, low boiling, garnering fans and accolades but never quite ascending to the heights they should have. And whilst one’s own demons will forever lay in wait, the decentralization of rap and the breakdown of the industry, along with the anemone now springing from it, have given crew members, artists on the coattails, the ability to rise up or fall down on their own merits.

Take Gunplay; a raspy voiced, semi-eloquent Cerberus, Rick Ross’ former weed holder has taken advantage of the rise of mixtape culture and YouTube to access avenues outside of a label’s purview and garner attention of his own, aside from Rozay. Rather then suffering a fate something along the lines of Roc-A-Fella’s early millennial Philadelphia flirtation (wherein Beanie Sigel, Freeway, Peedi Crack, et al. where to become the next big thing, but did not, a la Memphis Bleek and numerous other Jay Z proteges) Gunplay has effectively taken the situation into his own hands. He is not alone in this situation; Tyler, The Creator, Earl Sweatshirt, and Frank Ocean all sprung from Odd Future, where Domo Genesis and Hodgy Beats have struggled nobly, and not entirely in vain, for their own respect as well, while ScHoolBoy Q and Kendrick Lamar exist more outside of each other than as the Black Hippy collective.

A$AP Ferg comes from a situation more akin to OF than Q or Kendrick; he arrived as a member of a well organized, somewhat expansive clique, and although there are cosmetic differences, the most notable being A$AP Mob’s one ascendant star, rather than two, Ferg suffers the same challenges as Domo and Hodgy, namely, how to be recognized for the second half of his nom de guerre, not just the first.

“‘Fuckin Problem’ … platinum. Long. Live. A$AP. Number one album in the country. Sold out tours. What’s next?”

That brief but rather illustrious litany closes ‘Let It Go,’ the opening track on Trap Lord, and perfectly encapsulates the burden that comes with bearing A$AP in front of your name. It would be easy to see that stylized USD “S” and eagerly spin the record; even easier to notice the absence of the name “Rocky” after it, and write the project off.

To answer that question in brief, i.e., does Ferg both overcome and uphold the moniker of A$AP in this, his first major solo effort: yes. Ferg utilizes some of the best tricks in the A$AP aesthetic–harmonious, decadent ad-libs and choral layering; a sleek, dangerous kind of pretty infatuation with vice which either stems from, or in the least, dovetails with the groups’ infatuation with fashion (everything here could soundtrack images of the Fool’s Girls, all cream and blood lips, Isis eyes and high-waisted shorts, cigarettes, straws, utility knives, mirrors, brick walls, mattresses on floors, high socks on hardwood)–to make this unequivocally a Mob album, and then proceeds to lace said Mob album with enough personal flair to ensure it is his own.

Trap Lord bounces gleefully from misanthropy to poetry, sometimes in the same song; take ‘Didn’t Wanna Do That,’ which conflates having heart with a willingness to pull triggers on one verse, before advising later on that “you can’t live long living that street life.” Ferg does not approach these contemplative sections with the heart-breaking poise of Chance the Rapper, nor does he ride with the dissociative sangfroid of Chief Keef; Ferg instead oscillates about the middle, a lyrical analog to his infectious, steady, sing-song flow.

Ferg has a penchant for sharply barbed hooks; the wonderfully stupid ‘Shabba’ runs with the accoutrement run-down and a guest turn from A$AP Rocky, while ‘Fergivicious’ undercuts its boastful rhymes with a refrain of “All I know is pain,” and ‘Hood Pope’ stakes its melancholic bumper claims upon Ferg’s mournful plea to “let me sing my song.”

More than mere ear worms, such moments work well in juxtaposition to Ferg’s bars, which have a tendency to come fast and melodic; see him hang admirably with Bone Thugs-n-Harmony on ‘Lord.’ Befitting such vocal stylings, there is a kind of luxe, inky minimalism at work in Trap Lord’s production; imagine obelisks draped in Kanye West chains, lit by torchlight, and one comes close. Ferg is the energy and motion here, more so than the ubiquitous sweeping tones, or even the epileptic high hats and arrhythmic heart beats. A few cuts deviate from this dominant, enjoyable aesthetic: the miasmic, R&B tinged, Maad Moiselle supported ‘Make A Scene’ and the milky, fever dream trap house recollections of ‘Cocaine Castle.’

Guests turns are curated effectively; aside from the aforementioned Bone Thugs and A$AP Rocky, Ferg is joined by French Montana, ScHoolboy Q, and brother-in-currency Trinidad Jame$ on the serviceable ‘Work (Remix)’; better still is an appearance from Waka Flocka, whose typically energetic bars over the bloody strings of ‘Murder Something’ provide a nicely uninhibited edge that stands in contrast to Ferg’s tighter aggression. A wonderful pastiche of vocal textures is provided by D-Real, Onyx, and Aston Matthews on ‘Fuck Out My Face.’

Druggy, stylish, practically pleading to avail itself to house parties and room-crowding volume, there is no doubt that Trap Lord is an A$AP record, a given which, if it were the only criteria being met, would mark the effort as a failure. But Trap Lord is not an A$AP record; it is an A$AP Ferg record, sui generis, and that is its greatest achievement.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Momma

Welcome To My Blue Sky

L.A. Witch

DOGGOD