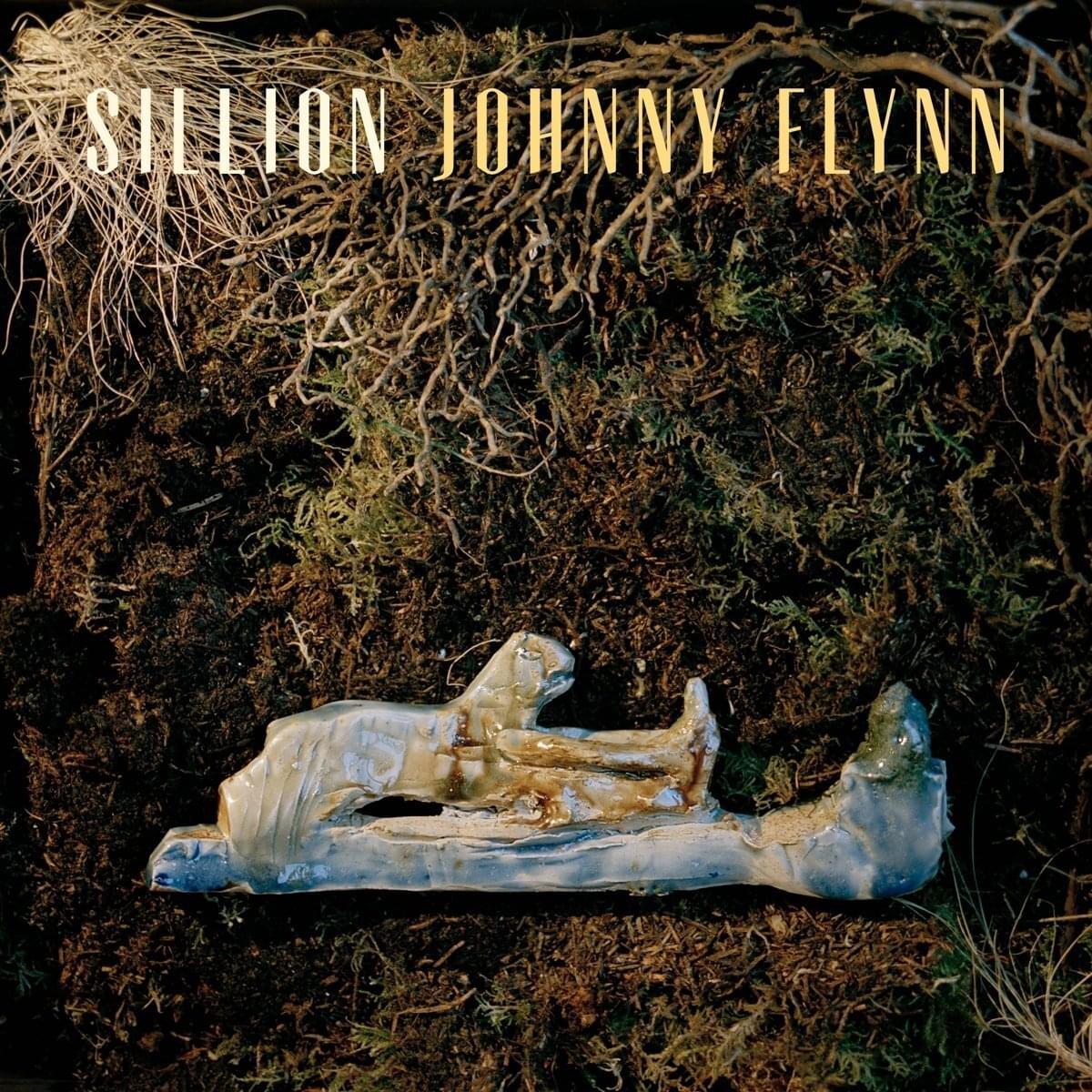

Mixed metaphors: Johnny Flynn on new album Sillion

Johnny Flynn’s brand of erudite folk first surfaced in the late '00s, riding the revival wave that brought us Mumford and Sons, Noah and the Whale, Laura Marling, and more.

Mumford et al took America, Noah and the Whale ventured into indie rock, and Marling embarked on what quickly became a prolific and highly respected career. Whilst the acclaim heaped upon this haphazard band of banjo-toting barnstormers ranged from the dubious to the deserved, Flynn took something of a backseat. The Sussex Wit singer-songwriter continued to craft his meticulous and measured tracks, just as he always had, steeping each offering in a blend of obscure and intriguing literary references.

Fourth album Sillion is no exception, with nods throughout to wordsmiths spanning several centuries-worth of literature. From the album title to the themes of mortality in lead single “Raising The Dead”, Flynn continues to capture the imagination of his listeners with his romantic depictions of life’s minutiae.

We caught up with Flynn the morning prior to Sillion's release, in order to help unpick the detailed tapestry of his latest body of work.

Your fourth album, Sillion, is out tomorrow. How are you feeling?

I had literally forgotten that! I mean, it sounds ridiculous, when I’ve written it, but yeah - it’s tomorrow! The album will come out whether I remember it or not, but we’re going on tour tomorrow for the first time in a few years, so that’s exciting for me! We’ve been rehearsing the past few days, so I’ve been focused on that. On these songs we’ve found a groove as a band that really fits us. Each album has been a progression towards finding a better fit as a live band, and I think the recordings really reflect that. The first thing you experience is the energy, and then - hopefully! - you think, ‘oh, I like this song!’

It’s really nice for me to be back making music, because I’ve been off doing acting for a few years. More recently I’ve done ten months away filming on different things. I’d finished tracking the record mostly by summer last year, then I’ve been away filming in that time and making sure I get all the last bits right. I feel like it’s a really whole piece of work now. I’m really proud of it. Whether or not people get into it the way I feel about it, I feel good. I’ve done it in a complete form. I only make music to please myself - I’m just filling gaps in my own record collection!

You talk about splitting your time between music and acting. How did your part in the play Hangmen affect the writing or recording process?

I was doing that while I was recording a lot of the record. There’s something about living in the world of another story whilst you’re trying to tell your own stories… of course you filter that into your own work. I was playing a psychopath, and in the end my character turned out to be a sort of avenging angel! He had cruel to be kind ethic. There’s a directness in some of the lyrics that was allowed because of that happening in my subconscious, exploring that side of human nature.

I’ve always been really drawn to people like that, who speak quite directly to me. People who I’ve picked as mentors, or leaders, or teachers… they’re not always sycophantic. They don’t stroke your better side; they challenge the parts of you that aren’t whole yet. I also like that in terms of musical inspiration. Maybe I’m a masochist!

Several of the songs on this record about people close to you, and the intimacy of family. How does it feel, sharing these personal feelings with all your listeners?

I definitely don’t tell my wife! If I didn’t speak with some honesty about these things, I wouldn’t really be an artist, or processing things in the right way. If you’re not generous enough to the universe, your audience, whatever, then it’s not a true interaction - it’s patronising.

At the same times, my songs aren’t so on the nose. They aren’t usually so literal - in a way, it’s an abstraction of the emotional landscape. Without sounding pompous, it’s about extracting the poetry of each moment. In a way, that’s more relatable. The physical reality of what has happened to me, or is happening to me on a day-to-day basis isn’t that relatable to everybody. These mixed metaphors act like a poultice; they extract feelings from people. That’s what I find exciting about good poetry. I’m not saying I achieve that, but it’s what I aspire to!

Poetry has played a large influence on this album as a whole, are there any particular poems by which you’ve been inspired?

Sometimes what I do is reference poets that have influenced me in the songs, or the names of the songs. That’s to announce where we’re going - I’m encouraging people to engage in that journey as well.

There’s a song called “Wandering Aengus” which is written after a Yeats poem called “The Song of Wandering Aengus”. To me, that poem is about having a mystical experience in nature, on your own, and the darkness and unknowable-ness of that. Sometimes nature is kind of terrifying, even in its minutiae! You see something that sends a shiver down your spine, and if you’re really fully having that experience that there’s probably nobody to turn around to and say, ‘I’ve just seen that!’

The first line [of the poem] is “I went out to the hazel wood, because the fire was in my head.” It’s a really beautiful, very lyrical poem. I was imagining, ‘What is the song of Wandering Aengus? The poem’s about this experience, and so I’ll try and summon that up and make it into a song.’ An actual song, not a setting of words to music, but taking the cue and going there.

The name of the record is Sillion, what does that mean?

That’s from another poet, by a poet called Gerard Manley Hopkins, a nineteenth century Jesuit priest. He wrote quite mystical poems. He was a Christian, but he was really into the sacredness of nature. I guess he was someone who said that you don’t need to go to church to have a spiritual experience. His poems celebrate quite simple, humble things.

In a poem called “The Wind Hogger”, which is about a falcon that glides on the current, the bird is looking down on a field, looking for the prey. One of the last lines is talking about the field that’s just been ploughed, and the earth that’s been turned over in the field he calls ‘sillion’. I think it’s an older word, and it literally means the thick, voluminous, shiny soil that’s turned over by the plough.

[The word] was suggested to me by my friend Robert MacFarlane, who’s a writer that’s been a big influence on me. He collects words. He’s written a book called Landmarks that’s collecting a preserving old idioms from regions, and words for things that we’ve lost now because of industrialisation. We don’t need to know the word for the hole that’s made by a hedgehog as it goes into a hedge - sadly!

- Jay Som announces first album in six years featuring Hayley Williams and Jim Adkins

- Circa Waves announce second instalment of Death & Love

- Big Thief explore love without shame on new single, "All Night All Day"

- Sex Week share new single, "Lone Wolf" and announce debut London headline show

- Tommy WÁ releases new track, "God Loves You When You're Dancing"

- Soulwax announce first album in seven years, All Systems Are Lying

- Gwenno shares title track from forthcoming album, Utopia

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Gwenno

Utopia

KOKOROKO

Tuff Times Never Last

Kesha

.