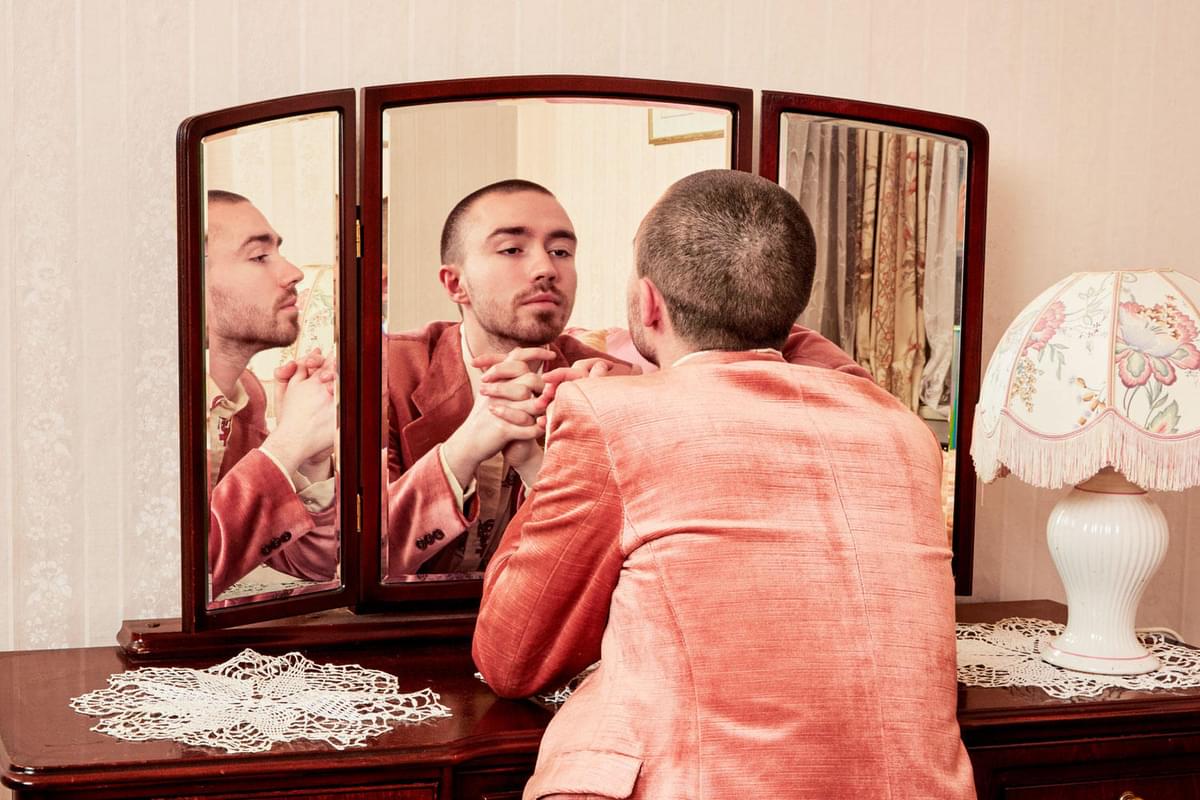

Matt Maltese on tragicomedy

Crooner Matt Maltese tells Best Fit how finding humour in the dark moments is the key to saving humanity.

I remember my first experience of tragicomedy being my English teacher putting on Four Lions: a heavy, of-the-moment film, where the main characters are terrorists preparing to bomb a marathon.

It’s no light subject matter, yet the journey is idiotic, hilarious and even pitiful. At moments you find yourself unnervingly sympathetic to the misinformation behind terrorists’ thinking and hatred. This was a first eye into the humanising power of comedy. Comedy didn’t just need to exist to the backdrop of lighthearted subject matter. It could shadow the darkest of moments in our lives and, what’s more, encourage dialogue and a sense of understanding.

Cue a gut-tearing first heartbreak, a few sobering years of early adulthood and countless depressing world events later, and I am myself a lover of - and believer in - tragicomedy. It is to me, the most useful cultural movement we have.

Like much of my generation, I spent a lot of my early childhood surrounded by Channel 4 morning sitcoms and platitude-filled teenage fiction and pop music. Everybody Loves Raymond, Friends, Westlife. Things that sell the happy ending. It is comforting in a certain way, granted. But I never felt comforted by the relatability of these stories. I instead felt comforted by hope that I too would have things that clear-cut and comical.

Pop culture is filled with comedies that sell the dream and undersell the reality, and I’ve always felt isolated by this form of comedy. Where does one fit if life’s grubby, laughably shit moments reach no happy ending? What if they just build into a different kind of existence where comedy and tragedy are indefinitely side-by-side? Enter, ‘Tragicomedy’.

Discovering the type of media home-county mothers might call depressing, changed my life for the better. Miserable comic king Leonard Cohen of course – but beyond that, today’s musical heroes of dark comedy: John Grant, Tyler The Creator, Courtney Barnett, Alex Cameron. All using the helping hand of comedy to open the door into uncomfortable discussions, and so help you relate and understand.

In recent literature it exists too. Novelists Bret Easton Ellis and Martin Amis of course, but a lesser known personal favourite which I’d recommend is Eleven by David Llewellyn, which hilariously depicts an office environment to the backdrop of 9/11, using comedy to poignantly illuminate uncomfortable truths.

And thankfully it is also experiencing a resurgence in one of the most accessible media platforms, Television. Lighthearted situation comedies are still in abundance, but the really important and noteworthy use of comedy has appeared in the form of shows such as Atlanta, Black Mirror, Flowers and the truly exquisite Fleabag.

Phoebe Waller-Bridge is a master of the tragicomedy and I would’ve made this whole piece about her if it didn’t make me seem such a kiss-ass. At first glance, it’s the story of a young London-dwelling woman struggling to work out who she is or what she wants from life, but it gradually reveals itself it to be this comedy-freckled dissection of heartache, grief, betrayal, and family relationships. It’s the kind of filthy, erratic tragicomedy we all need. The kind of show that - like all good tragicomedies - makes anyone affected by any of these things feel less alone.

One thing it does is make you sympathize with and understand someone who, in another light, we could simply write off as a wrong’un. This, I feel, is the most profound use of comedy: that as a welcoming entry into complex unsavoury characters and life-journeys. These kinds of television shows and uses of comedy inspire us to tackle the truth in modern-day life – however tragic and uncomfortable it may be - whilst also looking for the gags. Take Donald Glover’s Atlanta with its meditation on the black experience in the US, or Julian Barrett’s Flowers with its depiction of crippling depression. All these shows seamlessly use comedy to open up a conversation.

Personally, I can talk about my own hang-ups and heartache because I can also laugh with them. But taking them less seriously doesn’t mean they are less serious. Rather, it means I can open up without ego and write on the moments that feel like they shouldn’t exist in the realm of comedy - be it self-hatred, guilt, longing or nihilism.

Comedy is my segue into self-assessment. Don’t get me wrong, it has its dangers and many often rightfully feel it is an undermining force. We crack jokes about Trump, but he’s real and getting his way, and we make light of our own sadness whilst depression and suicide rates are through the roof.

There are moments where comedy stops being useful and starts being reductive and restrictive. But comedy is also becoming an increasingly helpful part of our important modern day debates - thanks not just to the new age of multifaceted Television - but to the openness of social media and the rise in meme culture; things that sometimes wonderfully segue into actual discussion of unapproachable topics.

Whilst many see these as wholly bad things, I think it opens difficult conversations that were previously not being had. That’s why I think tragicomedy can save us all.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Tunde Adebimpe

Thee Black Boltz

Julien Baker & TORRES

Send A Prayer My Way

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE