The Beauty That Remains

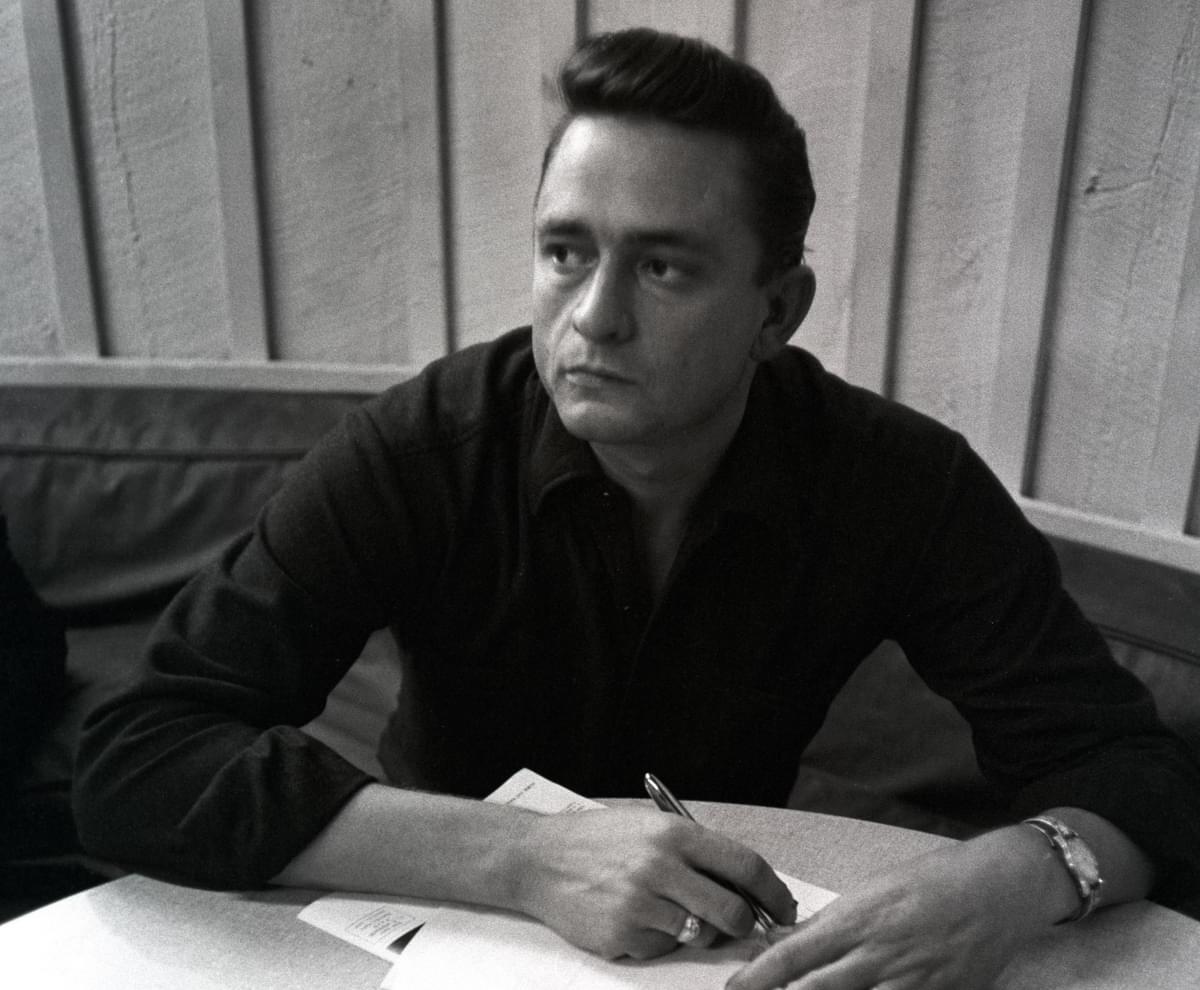

Forever Words sees the poetry and lyrics Johnny Cash left behind set to music for the first time. His son John Carter Cash tells Jof Owen about the musical ghosts that inadvertently ended up haunting them.

“He was my best friend, he really was. For years and years. We had fun together. We laughed together. We enjoyed life together. He could be a goofball. We went on fishing trips and we did all these different things that a son and a father do, and we developed a friendship and a kinship beyond the respect that a son has for his father. So doing this whole project has been about getting back in touch with my father as my friend, and remembering his personality.”

John Carter Cash is talking about the weight of his father’s cultural legacy. The only child of Johnny Cash and June Carter, John talks in a purposeful, calm measured way, as if finding his footing with every sentence; as if he knows the weight of every word. It's understandable given that this is the man handed down the responsibility of caretaking the heritage of one of the last century’s musical icons. Working with a disparate array of artists - from Elvis Costello and Chris Cornell, Kacey Musgraves to Philip Glasper - John and producer Steve Berkowitz have reimagined poetry and lyrics left behind by Johnny Cash as new musical compositions, resulting in one of this year’s most innovative and affecting collections.

“It began with the fact that my father’s words touched me," John tells me. "When I looked through his papers after he passed away and I focussed in on all of his writing and all of his own compositions I knew there was a clear picture there of his life as a whole, with all its intricacies and all its absurdities, with all his humour, every word exposed with all the darkness that was there, but all the beauty just as evident.

"Dad always wrote. Words were written on everything. These were bits of paper that just contained the words. It doesn’t have to be any kind of paper, but they were my father’s words. He was a pack rat. He put things away and he never threw anything away.”

There was a huge archive of material to wade through, mostly previously unpublished and completely unknown until John began digging through it. “There were two thousand five hundred pieces of material," he explains. "There was poetry, there were things that he wrote that were just very significant – thoughts and philosophies – and there was page after page of biblical study notes, and things that he’d started and then just set aside. Then there were personal things that I would just never share myself, because I wouldn’t feel I had the right. Out of all these pieces there were over two hundred and fifty pieces of material that with the help of some research I determined were unpublished. I truly believe in my heart that if my father had been a professional bowler or a milkman then I would have wanted to see such beautiful brilliant words put into a book.”

Working with Irish Pullitzer prize-winning poet Paul Muldoon and Berkowitz, John edited the original two hundred and fifty down to the forty one pieces that were compiled for the original Forever Words book, but he always saw this as the starting point, rather than the final destination for these pieces. “I always heard melody and I always saw the potential for music being added," John says. "I had to get to the point in my heart and in my mind where I felt like this is what he would’ve wanted me to do, and I have no one to answer to for that but me.”

Understanding when the pieces were written, and who they’d been written about or meant for, became one of the biggest challenges of the project. Sometimes his father would have annotated them - either with an inscription or, if it was intended to be sung, a guideline to what sort of artist should sing it - but mostly it was left up to John Carter Cash to do the detective work.

“The pieces range all through the years too," he explains. "Some of them were dated and some of them weren’t. My opinion is that 'The Captain’s Daughter' and 'What Would I Dreamer Do' are the oldest pieces. You can tell by the handwriting or what kind of paper it was written on. They were written when he was twelve or thirteen. If it’s one of those notebooks where you tear out the page and it’s spiral bound then I know it must have been written later because they didn’t start making those until the seventies.

"'Going, Going, Gone' was written around 1990. He was right out of a hospital from surgery and he’d been in a recovery centre just before he wrote it. Then there was one piece that had the Delta Airlines logo on it and I looked it up and they only used that logo between 1958 and 1959. So we used things like that to date it, but then his handwriting also consistently changed through the years.” John describes it laughing as having been like going to ”Johnny Cash graduate school.”

The artists chosen to write and perform the sixteen songs on the album match the huge variety of pieces that John Carter chose for the collection. It’s an album of mainstream misfits, who occupy the same uncomfortable space in contemporary music that Cash often did; artists who, despite their commercial success, have often felt the “cold winds of exclusion”, as Johnny Cash once described it, blowing their way. John Mellencamp rattles up a version of 'Them Double Blues' while The Jayhawks slouch their way through 'What Would I Dreamer Do'. Alison Krauss is reunited with Union Station for 'The Captain’s Daughter', and Jewel sings 'Body On Body', one of the pieces that Johnny Cash had marked out to be sung by a female singer.

Elvis Costello provides one of the album’s standout moments performing the countrypolitan tearjerker 'I’ll Still Love You'. As John Carter explains, “my father wrote that for my mother. It’s just about that idea that “I’ll still love you, no matter what, even when I shut my eyes at the end”.

The collection is full of moments like this. Moments that become even more emotionally loaded once you know the backstory behind them; when and why they were written and where they fit in in the timeline of Johnny Cash’s life.

It begins with "Forever/I Still Miss Someone", a poem written by Johnny Cash read here by Kris Kristofferson, accompanied by Willie Nelson picking out the Cash classic 'I Still Miss Someone' on his long serving acoustic guitar, Trigger. “You taught me that I must perish like the flowers that I cherish”, Kristofferson reads dolefully. “Nothing remaining of my name / Nothing remembered of my fame / But the trees that I planted still are young / The songs I sang will still be sung.”

“He wrote that weeks before he passed away”, John explains. “To have that essential hope at that point in his life, after the love of his life which he spoke of had moved on, is something that I personally would hope for; to look and see that the legacy that would follow would be very strong. And here we sit, with all these years passed.”

"The age difference between Kacey Musgraves and Kelly Ruston is the same as my mother and my father, and they’re so much together in their heart, and it just connected right in my spirit."

"Forever/I Still Miss Someone" is thematically paired with the Ruston Kelly and Kacey Musgraves duet, 'To June This Morning', that follows it. It’s one of two songs on the album that weren’t drawn from the poems and lyrics in the original Forever Words book. When he was approached to write for the album Kelly revealed that he’d coincidentally already written a melody to go with a poem of Cash’s that he’d come across twelve years earlier in a book of Johnny Cash fan memorabilia. John hadn’t ever seen or read the poem before Kelly showed it to him, and immediately welled up at the personal significance of the dating of it. “That poem was written in February of 1970 when my mother was eight months pregnant with me, which is the conception of that hope," he tells me. "The Kacey Musgraves and Ruston Kelly track ties directly in with the hope that I was talking about in the song 'Forever', and the inception of so much of that hope that remained throughout my father’s life. It’s very beautiful. It’s a simple beauty of being in a moment. It’s just the honesty of it.”

Carter was drawn to the parallels he saw between his parents’ relationship and newlywed country music golden couple Kelly and Musgraves: “It was serendipity. I truly believe that it was meant to be. It connects on so many different levels. The age difference between Kacey and Ruston is the same as my mother and my father, and they’re so much together in their heart, and it just connected right in my spirit.”

In the end it simply became about choosing artists that would respect his father’s words and who would, at the same time, connect with the spirit of his father. He contributes the ease of the recording process to that innate connection that the artists all had with his father.

“Each of the artists involved with the project have their own relationship with my father’s music or they have their own relationship with his music and it happens to be their father or it happens to be their step father or it happens to be two of my dad’s best friends. Kris Kristofferson sent me a gift the day I was born, so I’ve known him my whole life, and Willie Nelson since I was very young. I toured with The Highwaymen when they were working together. I was one of their road managers in the early nineties, and Waylon was always around the house. Then there were artists on this project that didn’t know my dad, but I know his heart and I know what he loves. It’s all part of my father. I would ask myself what the best platform would be for a lyric like Going, Going, Gone. I wanted to put it into the hands of artists that would really make a difference with what he was trying to say with the message of anti-drugs and anti-addiction, and facing your own demons. Just at least to acknowledge what drugs had done to Dad.”

As the project developed, John Carter learned to adapt to and trust the instincts of each artist, often letting them lead the way with the recordings. “Jamey Johnson just walked up to the mic and he looked down at his piece of paper and he had his guitar in his hand and then he just started singing and the whole song came out and I was recording it. Same thing happened with Brad Paisley. They wrote them note for note on the spot and I recorded them.”

Although it’s one of the few tracks on the album that John Carter didn’t record, the process had been the same with Costello‘s "I’ll Still Love You"; writing it and recording it in one take for the first time. Carter has a fondly retold anecdote for each of the recordings on the record and talks wide-eyed about the processes that were involved in their writing; how they all came about in such different ways depending on each individual artist. It’s the Chris Cornell track "You Never Knew My Mind" though that seems to resonate most profoundly with him.

“It was different with Chris Cornell. He really took his time with it. It took him a while. It was a few weeks before he sent me back the demo of "You Never Knew My Mind", because for him it was a spot on precise signature that he wanted to make sure aligned with him honestly and with my father honestly too.”

Recorded, like the majority of the album, in Cash Cabin Studios, the home studio that Johnny Cash built in the late seventies less than a mile from where he originally lived with June Carter, that John now operates from and where he recorded the last four of his father’s American Recordings albums under Rick Rubin, it’s one of the recordings that he’s most quietly passionate about and understandably proud of. “Making this record was just like being at home, it really was. The Chris Cornell track is like an orchestra of chaos coming down all around him, but it’s still the heart and the message, and it ties in with the way my father did his work. The Cash Cabin Studio is just stone and wood, but my dad’s spirit is still hanging out there. At least for a while,” he laughs.

“Chris took it very seriously and it took him a few weeks to come back and to give me the song and when I first heard the MP3 on an email of 'You Never Knew My Mind' it made me nearly cry.” It ended up being one of the last recordings the Soundgarden singer would make, following his untimely death last year.

"Chris Cornell had such a humble spirit - except when he would be screaming onstage - but as a human being he was so humble."

“When it came to working in the mix that was really heavy because it was after Chris had passed away. I had got to know Chris better through the whole recording process. I met him backstage in the nineties at a Johnny Cash show in Seattle. I’d just performed with Dad and Chris was backstage after the show, and he told me my dad was one of his biggest influences musically in his whole life. I got to know him a little, but then through this project I got to know him a lot, in my own way, through the camaraderie of working together. We both went fishing with our dads in Canada when we were kids so we’d talk about that, and he’d bring his kids on the road so he’d ask me how it used to be for me growing up, travelling with my dad on the road and how I felt about that. Recording with Chris was an amazing experience.”

The song, reimagined by Cornell from a set of words that Johnny Cash had written towards the end of his relationship with his first wife Vivian, has taken on an even greater poignancy since his death.

“It’s such a beautiful song. I got to know Chris, and he was in a wonderful place when he wrote it. He was in a place of peace, and in a good spot. He looked back over the relationship that he’d had, that had finished, just as my father did, and this is the music that came out. You can read a thousand things into these words now, knowing what happened later. Working in the mix of this song it was overwhelming, but it’s great to have been a part of the process and to witness what happened. He was like a lion with the heart of a lamb with a thorn in its side. He was so gentle. Chris had such a humble spirit. Except when he would be screaming onstage, but as a human being he was so humble.”

John takes one of the heavy sighs that so often punctuate his sentences, before continuing: “It overwhelms me, it really does, and that’s about it. It’s the beauty that remains. My father could express the emptiness and still find hope. There were times when my father could have fallen down just as hard as Chris ever did, but the beauty that is there remains no matter what, and we can touch the soul of that and feel our own desperations inside and connect with my dad. He showed his frailties and Chris does too, and that’s part of the beauty to me.”

Elsewhere on the album John worked with two of his step-sisters - Carlene Carter, June Carter’s daughter from her first marriage to Carl Smith; and Johnny and Vivian Cash’s daughter Roseanne. “If I’d have heard 'Walking Wounded' on one of her albums there would be no denying it’s a Roseanne Cash song. I gave this one to her because I knew it was something she could connect with. Dad wrote it about post traumatic stress, because he was suffering with post traumatic stress from his own living and he was in physical pain at the time too because he’d broken his jaw. So 'Walking Wounded' is just the pain that we carry around from our past experiences, and that was something that Dad felt like he understood and that we can all relate to, but it’s also about understanding that sometimes someone else’s pain is greater than yours.”

"It’s a catharsis and a healing as much as it is anything...when I look at the words I’m hearing the voice of my father in a way that I haven’t before."

The album ends up working in the opposite way to the American Recordings albums. On those albums it was Cash drawing inwards from all around him, bringing in songs that resonated with him wherever he could find them. Forever Words takes that process and reverses it, with the artists drawing back outwards again from Johnny Cash. Everything here begins with him, but ends up in an entirely different place. “This project is about focussing on the words," says John. "It’s about the mystery, and the more that we dig the more mystery we find. He had such depth of nature, but the truth of the matter is he was also very simple in his heart. He was of the American soil. He followed his dreams and this is what happened. He failed, he messed up, he hurt. He definitely did, but when he fell down he got back up and he kept going. And he died young, but with a lot of years under his belt.”

With the completion of the project and the release of the album it feels as if a weight has at last been lifted from the shoulders of Johnny Cash's son. A project that had begun as something of a necessity for him to put together at a certain point in his life has come full circle, and listening to him talking proudly about Forever Words it's clear that this spiritual journey he ended up taking has finally come to an end. “There are so many reasons why I did this. It’s a catharsis and a healing as much as it is anything," he explains. "I’m 48 years old. I was much younger, in my early thirties, when he passed away, and at this point in my life I’m in a different place. I see through different glasses and read through different glasses and I’m hearing things that I wouldn’t have heard before. Or didn’t hear before. I have a different tuning in my ears, and in my heart also. So when I look at the words I’m hearing the voice of my father in a way that I haven’t before.”

As for a possible follow up to Forever Words, he says there aren’t any plans to do anything more with the pages and pages of writing that his father left behind. “There is more music though,” he teases. “But that’s all I have to say about that right now.”

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday