David Bowie, Germany and the Future

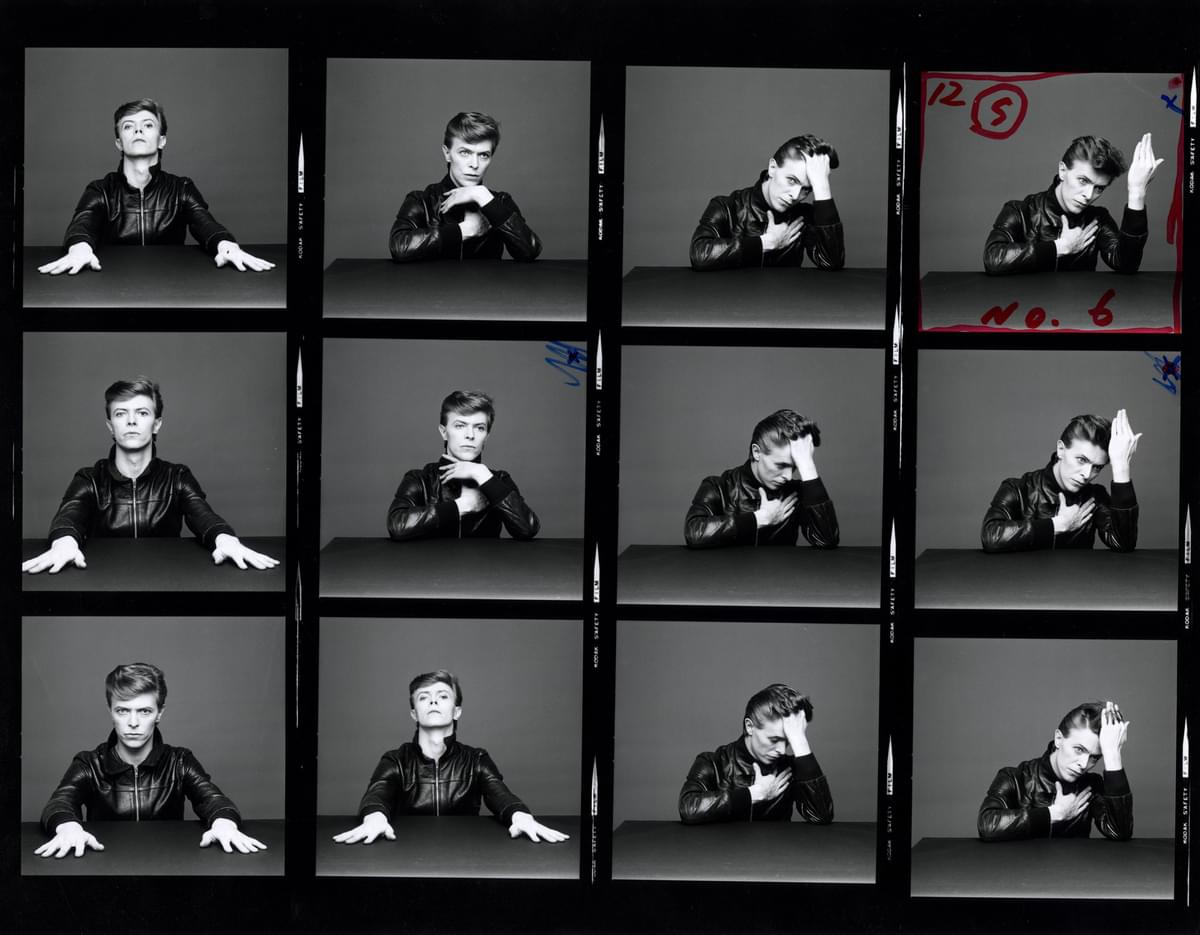

As David Bowie prepares to release a new album on his 69th birthday, David Laurie looks back on his rampant experimentalism in mid-70s Berlin that saw him tear up the rule book and refuse to read it ever again.

It wasn’t possible to go through life and not notice David Bowie’s existence in the early Eighties, even before He came back, reinvented as a hit-packed, global stadium-busting brand, with "Let’s Dance" in 1983.

He had not put an album out for a few years, an occurrence not seen since the mid Sixties, such was his prodigious Seventies catalogue, but there had been recent hits with Bing Crosby, Queen and Giorgio Moroder, along with covers of Johnny Matthis and Kurt Weill. Who else could connect with such a broad selection of artists? His last album alone [Scary Monsters] had featured members of The Who, King Crimson and The E Street Band. Bowie’s tendrils in Pop culture were everywhere - you didn’t have to seek Him out. If one walked into a record shop, one would be greeted by a Bowie record without having to look for it in the racks, ChangesOneBowie, ChangesTwoBowie; iconic renderings of His face beamed down from posters and up from magazine racks, He was on the radio and TV, talking about his stage plays and films. If He wasn’t doing the talking, then someone would be holding Him up as an inspiration, sine qua non. What was the fascination with the man?

It was not ever so, nor had this endless kudos been easily won. Bowie had struggled to find his way musically throughout the Sixties, flitting from one trend to the next without making much impression but finally scoring a novelty #1 single, on the back of a global obsession with the space race in 1969, with "Space Oddity". Novel it certainly was but this peerless song of dislocation, mirroring His own inability to connect with His Muse or find an audience, was the first time you truly felt magic at work on a David Bowie record. He clicked with Himself for the first time and the public felt it too. And so it began.

His peerless run of albums throughout the Seventies raised and reset the standard for pop music, time and again. As an unfaltering body of work, it stands unequalled and seems likely to remain so. Starting out with literate and alchemical hippy music on "Space Oddity", he moved through the earthy and epic psychedelic rock of The Man Who Sold The World, into the spaced out and very feminine sci-fi folk of Hunky Dory. His staggering, feline performance of "Starman" on Top Of The Pops in 1972 was the game-changing moment in which everyone in Britain noticed What Had Become Of David Bowie. Debuting proto-Ziggy hair and dressed in a skinny catsuit, seemingly made of curtains, with His arms draped around Mick Ronson, who wore the sort of blonde feather cut and catsuit combo that Charlie’s Angels would later popularise, they made An Impression. Bowie was batting for both sides and knocking it out of the park, playing straight to camera. His voice dipped and soared again with total control; a consummate performance. You can’t half watch its pure, devastating theatrics. Once in a while a singer can burn a song, every single nuanced word of it, straight into your memory, a sparkling, livewire connection, that is never forgotten. That is the magic of music and it’s surprisingly hard to maintain that magic on television.

It’s rare that someone who puts that much effort into making your jaw drop at their appearance can make it drop yet further with the music. He had been practicing being David Bowie for a long time and on that Top Of The Pops, He contrived to make it look easy. Bowie’s slow burning superstardom, His love of and success with masks, make-up and characters mirrored that of a hero of His, Peter Sellers. They both insisted that they themselves were quite uninteresting and “had no personality” of their own and were thus willing, able and even desperate to fully commit to each role, each performance.

David didn’t just become Ziggy Stardust; at the same time He severed ties with the business of being David Jones.

Bowie’s next inspired decision was to allow each side of his music, of his mind, out at the same time; to meld the thrusting, riff rock of his imagined Saviour Machine into the receptive, circular ripples of Hunky Dory to create the two dimensional androgynous rock star template for Ziggy Stardust. A creature of pure ego, a pleasure seeker, neither bound by responsibility nor mired in routine. Then, just as predicted in His own lyric, “making love with his ego, Ziggy sucked up into his mind”, David was willingly subsumed into His own chaotic creation and fulfilled His stated destiny, as revealed in the slip from third person to first at the end of His theme song; “when the kids had killed the man, I had to break up the band”. David didn’t just become Ziggy Stardust; at the same time He severed ties with the business of being David Jones.

Having ruthlessly discarded The Spiders From Mars onstage, He took his bold Psychological Rock experiment further out and made a bid to conquer the States, manifesting Aladin Sane’s schizoid, ambisexual passions and riding Diamond Dogs’ decadent cocaine tailspin deep into the heart of America. His fear of flying meant that he experienced the vastness of the country, gas station to gas station, at ground level. The endless highways dwarfed and consumed the overdriven ego of His sundry personalities, and brought his role as A Rock Star to a nominal End Of Part One; as Bowie Himself ran out of gas.

This period was captured perfectly in Alan Yentob’s brilliant documentary, Cracked Actor. Bowie is seen as a man teetering on the fine line between confidence and collapse, stick thin and babbling about Aretha and the Soul Of America [just as Bono would do, somewhat less convincingly, ten years later], wide-eyed with cocaine and ambition. His rambling English tones hopelessly out-of-place on the long hot limo rides across the American desert, his monologues careering in and out of making sense. He’d have looked out of place anywhere and Nic Roeg, on seeing the film, saw that quality immediately and cast him as the Alien in The Man Who Fell To Earth. That “not quite human” quality was deployed again to great effect in the Broadway production of The Elephant Man a few years later. Taking leave of your senses is not without its own rewards.

No-one predicted the well-spoken Englishman’s rebirth, a few months later as a Young American Soul diva, nor his succession of funky American #1 singles. After winning at Disco and planting His flag in the black music heartland of Soul Train, just as he had on Top Of The Pops a few years previously, David rounded up his few remaining unchipped marbles in an LA studio and let Europe seep back into his mind with Station To Station. The icy croons and machine-tooled sci-fi soundscapes, some of which had been conceived for his abortive The Man Who Fell To Earth soundtrack, were heavily influenced by the dehumanised noises of Germany’s synthesizer pioneers, Kraftwerk and the snaking, locked grooves of Neu!

Between 1976 and 1978, Bowie was in mad professor mode, secluded away in studios in Berlin and the French countryside, aided variously by Brian Eno, Iggy Pop and producer Tony Visconti. Together, they rebooted and expanded Pop and Rock Music in ten different directions with each successive album. As Punk thrashed around lustily at The Stooges’ old ideas at home in London; Low, “Heroes” and Lodger, along with Iggy’s The Idiot and Lust For Life drew upon and blended aspects of every genre imaginable to make A New Music. It’s neither fair nor sensible to discuss the Berlin trilogy without including these Iggy records.

These albums represented a masterful destruction of the foundations of the phallocentric Rock music that had powered Ziggy’s swagger and strut. Bowie seemed to have prised his altered ego’s grip from the reins and given the musical lead to His feminine side, allowing the glistening songs to pulse and grow, to draw the listener in, rather than batter them over the head. There was an introspective and self-critical aspect to the words and music; along with a slightly humbled sense of doubt and no little wonder. He took a step back and let the music find its way, no longer feeling compelled to preen and yelp all over the tunes. The albums sounded big, beautiful and eerie but accessible, filled with melody and bathed in light.

The “low profile” visual gag of Low’s sleeve, those important speech marks around “Heroes” and the impermanence of calling yourself a lodger are not bullish Rock Star statements, there’s no more of The Big I Am. Instead they speak of questioning experimentalism, of breaking bad habits and learned megastar behaviour, no longer “always crashing in the same car”. Iggy’s self-realisation was even more blatant and, not that the man had an excess of shame to begin with exactly, but calling your album The Idiot still takes balls. His rediscovery of his own Lust For Life just as transformative, and twice as infectious.

If Ziggy lived and died as the ultimate Rock’n’Roll animal, then the second half of the Seventies saw Bowie bury Rock’n’Roll in the grave right next to him; and it seemed as though every cool band in Britain was attending the funeral.

The results are stunning and gave life to the “European Canon” He had announced/imagined in Station To Station’s lyric. A new music that had nothing much to do with Rock’n’Roll but still delivered thrills and sounded, if anything, bigger than ever. Stadium sized music that had not evolved from basement clubs. An alien, computerised music that practically demanded white lights and lasers onstage. Close Encounters of The Third Kind came out in 1977 and the aliens seemed to originate from the same planet as Bowie’s grand, unfamiliar tunes, similarly dotted with machine-noises, pulses and throbs. These were tunes that often had no recognisable instruments and sometimes seemed untouched by human hands. If Ziggy lived and died as the ultimate Rock’n’Roll animal, then the second half of the Seventies saw Bowie bury Rock’n’Roll in the grave right next to him; and it seemed as though every cool band in Britain was attending the funeral.

He was pulling back the curtains on the sci-fi future that hadn’t quite materialised after the Space Race in the Sixties. Each single sounded completely different to the last and the excitement to see what He’d do next made each one An Event. "Fame", "Wild Is The Wind", "Golden Years", "Speed Of Life", "Be My Wife", "Breaking Glass", "Sound And Vision", “Heroes”, "Boys Keep Swinging", "DJ", "Ashes To Ashes", "Fashion". A trailblazing comet, He was hard to keep up with but a source of constant illumination. His work rate gave drug addicts a good name and made bands who hawk around the same set for years on end look lazy beyond words. It also made sounding like Bowie virtually impossible. In the months it would take a band to dissect a record and spin it somewhere new, He’d have moved on, leaving them standing. The only thing that bands could hope to copy was his refusal to repeat himself.

This restless, inventive attitude to making music, and the freedom it engendered, inspired the thinking behind so many Eighties Pop groups. After Low and “Heroes”, all the cool Pop albums from then on had weird and unusual tracks among the Proper Actual Songs. I miss that a bit. Trying different things and leaving songs as experiments for the sake of it, without trying to force a chorus onto them, makes for deeper and more interesting albums. There is no shortage of invention today. Quite the opposite really, as the internet makes the all world’s noises a click away, but it rarely troubles the Top Ten any more and those sonic adventurers have less time for Pop music…

…and yet Bowie’s rampant experimentalism is now seen as His Imperial Phase. He tore up the rule book and refused to read it ever again. He wouldn’t settle on his laurels for a minute but, at the time, this asked a lot of some of His fans. Not everyone likes ch-ch-changes. Least of all his label who, on hearing Low, offered to buy him a big house in Philadelphia, where He had made Young Americans, if He would make another Soul album. Record labels really like it when artists repeat the winning formula because casual fans, who buy the bulk of the albums when an artist crosses over into the Top Ten, very often prefer repetition to Repetition, it seems.

A new and unfathomable record every few months meant that these European albums were not, by his standards, huge sellers at the time. Having pushed His creative impulses into virgin territories, He finished off the Seventies with the double tap of "Ashes To Ashes" and "Fashion", which surfed the coming Synthpop revolution that he’d helped to kickstart, to be huge worldwide hits. They sounded like David Bowie songs, albeit unlike any that had come before, and were packed with unstoppable hooks and flourishes that made radios play them all over the world. They were set amid the otherwise quite dark and dystopian (and brilliant) Scary Monsters, which harked back to Diamond Dogs in terms of lyrical content and scraping guitar noise, and proved to be an equally crowd-pleasing move. Just as with 2013’s grand comeback The Next Day, the sleeve of Scary Monsters features whited out versions of His older record sleeves, including “Heroes”, and it makes the album feel like a wrapping up of the Seventies and the End Of Part Two for Bowie, just as Diamond Dogs had felt like and End of Part One.

The abundance of new noises on Bowie’s records were mostly out of the reach of the legions of bands who were following his every move. Early synthesizers cost as much as a Ferrari and so, during the Post Punk Years, bands looked to find DIY alternatives to Moogs. Recording studios looked more like workshops; with cumbersome homemade machines, oscilloscopes for monitors and modified tape reels contrived to make time-stretched clicks and pleasing whirrs, in order to render their own post-guitar landscapes. A lot of Post Punk’s wonderful singles were inspired by Bowie’s purging of rock’n’roll, the removal of ego and human warmth and the harsh industrial noises heard on sides two of Low and “Heroes”. These stark 45s are nonetheless alive with ideas and urgency; twitching with political unrest, their messages delivered mechanically and angrily but, as much as I love Cabaret Voltaire, early Human League and PiL, their spiky singles were quite intentionally not dripping with mass appeal.

The abundance of new noises on Bowie’s records were mostly out of the reach of the legions of bands who were following his every move.

If Bowie was the figurehead behind this change of attitudes and sounds, He readily acknowledged that He wouldn’t have got there without Kraftwerk and Neu! The two German bands’ roots intertwine and stretch back to the Sixties. Neu! remained more underground due to their lack of structured Pop melodies but Kraftwerk had maintained a steady cult presence in the UK. The Man Machine (1978) and Autobahn (1974) had been Top Ten albums. Bowie had asked Neu! to contribute to Station To Station but they declined. Regardless, the first five minutes of its epic title song is a Neu! track in all but name. Neu’s music is less obviously electronic; using other methods to dehumanise it. Their long songs are largely instrumental and use endlessly repeating figures that develop very slowly. Klaus Dinger’s drumming, while human, is very metronomic. The groove, once assembled, is adhered to with only the most subtle variations. Michael Rother’s sparse guitar playing bears shadows of Minimalist modern composers like Steve Reich and Terry Riley. The whole thing sounds clean and perfect. There is no suggestion of blood, sweat or tears on display whatsoever. Neu!’s slowly fluctuating, yet elegant and persistent tunes were not big sellers but came to be very influential, not just on Bowie but also Eno for his ambient albums and through those artists, a whole generation of Pop groups in the Eighites, Nineties and beyond. Neu’s music is not difficult in any way and, if you haven’t, you should give them a listen. It’s not too fanciful to extend the throughline from them on to the pulsing hypnotic soundscapes of modern electronic music.

Both Kraftwerk and Neu! were not just distinctive musicians but also masterful conceptual artists. The reductively functional band names and utilitarian Pop Art sleeves, when coupled with the willing removal of their physical selves from the spotlight, speaks of trying to make a futuristic music that owes way more to the Avant Garde than it ever did to ego or Rock’n’Roll. Kraftwerk’s willingness to be seen to relinquish the creative and performance processes to machines is a product of growing up in the Sixties with Warhol’s Factory screenprinting mechanisation and their fondness for avoiding the indignity of labour displays knowing winks to ’s Dadaist shortcuts.

Buy Dare: How Bowie & Kraftwerk Inspired the Death of Rock 'n' Roll and Invented Modern Pop Music

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

MF Tomlinson

Die To Wake Up From A Dream

Gwenno

Utopia

KOKOROKO

Tuff Times Never Last