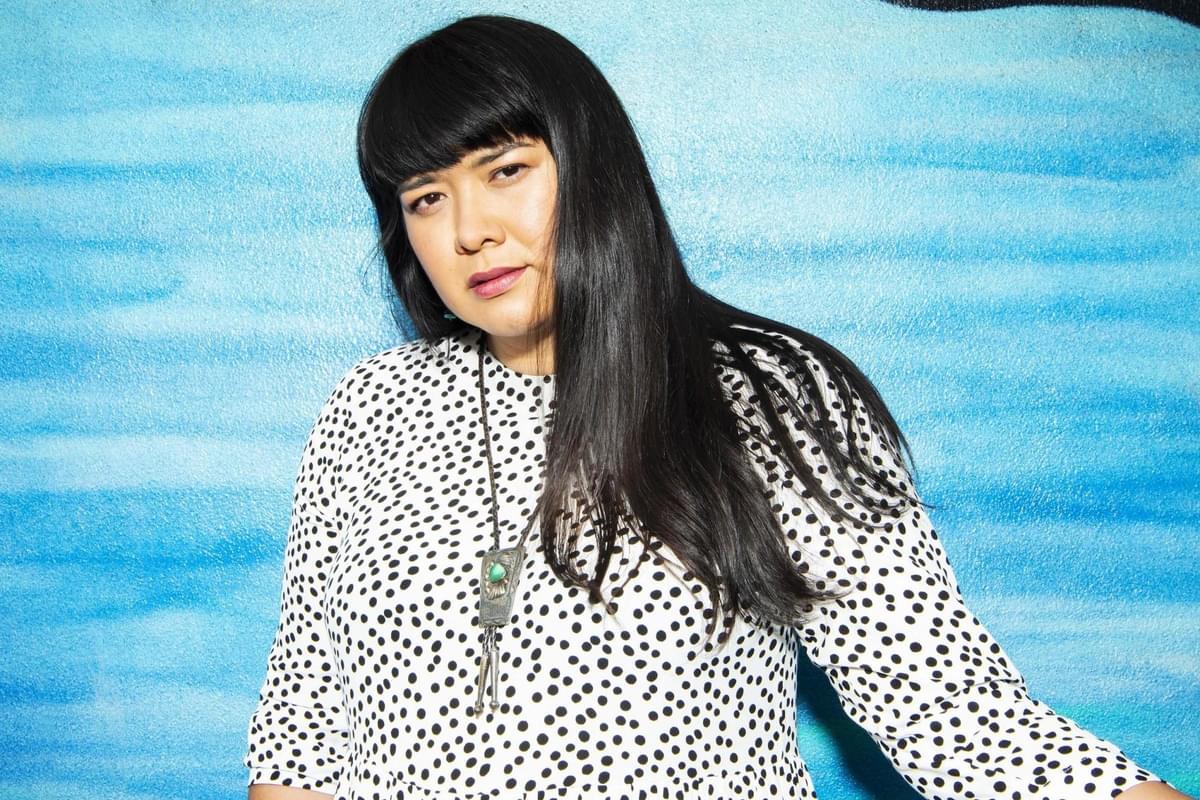

At The Party with Black Belt Eagle Scout

Struggling to balance her identities as a queer woman and Native woman, Katherine Paul's latest release is a celebration of self and some of her most important POC relationships to date.

Growing up in the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community in Washington state, Paul was eventually lured away by the riot grrrl and grunge scene of the Pacific Northwest - home to Bikini Kill, Hole, and Nirvana. A self-taught guitarist and pianist, she eventually became involved in the queer creative community in Portland and it was here Black Belt Eagle Scout first took flight.

Right before Australian indie-rock trio, Camp Cope played a nearly sold-out Warsaw in Brooklyn, lead vocalist and guitarist Georgia Maq took to the microphone. She introduced Sachem HawkStorm, the Chief of the Schaghticoke First Nations and a direct descendant of the great Wampanoag Chief Wasanegin Massasoit, to welcome the band to perform on the land of the Lenape peoples.

A clearly emotional Maq, with her voice cracking, spoke of her gratitude of introducing her set with Sachem, and that it was a privilege to have him on the stage as her band was about to play on stolen land and to acknowledge and honour its first inhabitants. “I acknowledge and offer deep gratitude to this Lenape land and water that supports us, as we’re gathered here right now together, and I invite you to join me in that acknowledgment, that respect, and that gratitude,” addressed Maq. Land acknowledgment is a simple, but powerful, way to show respect to Native American land and to recognise the long-lasting relationship between Indigenous Peoples and their traditional territories.

Katherine Paul comes from the small Swinomish Indian Tribal Community in northeast Washington state, with its population no more than roughly 1,000. Having been drawn to the DIY ethos of the music scene in the Pacific Northwest, Paul eventually moved to Portland, Oregon, where she is now based, writing and recording as Black Belt Eagle Scout.

Black Belt Eagle Scout’s first record, Mother of My Children, which was re-issued by Saddle Creek in 2017, is full of melodic indie-rock doused in dreamy guitar tones. Paul often writes about her life and her identity as a Native, brown, queer musician, intertwining themes of love and loss.

But Paul had been playing songs from Mother of My Children for quite a long time by the time it was re-issued by Saddle Creek, and was craving an opportunity to delve into fresh material. While Mother of My Children is characterised by motifs that explore longing and devastation, her second full-length record, At the Party With My Brown Friends is a celebration of the most important relationships in her life. The sophomore release finds Paul reflecting on the friendships and partnerships that matter most to her – especially those that make up the core of her incredibly important brown community in Portland.

Recorded over the course of nine months, Paul played all the instruments and produced the whole record. The sprawling guitars of her debut record are exchanged for softer vocals and atmospheric keys to create a piece of art that is raw, delicate as it is all-consuming and emotionally powerful.

“I write a lot about my life,” Paul tells me. “I found that a lot of the songs I was writing had to do with friendship. A lot of them had to do with supportive relationships. and with love and connecting. Some of them are from the past year or so, and I was looking at them and thinking, ‘How can I put these together? How can they relate to each other?’”

Black Belt Eagle Scout initially began as a side project for Paul over a decade ago, after Paul had become disillusioned playing as a drummer in various bands. As the only person of colour in the groups she played in, she struggled to relate to the lyrics that the rest of her bandmates were writing, and decided to create her own musical project where she was free to express herself and explore her identity as a queer brown woman living in Portland.

“There’s this freedom of being able to do whatever I want if I want because this is my project and I have control over it. I've definitely noticed differences in other bands that I've been in terms of just you know, being a person of colour in the band,” says Paul.

“There’s this freedom of being able to do whatever I want if I want because this is my project. I've definitely noticed differences in other bands that I've been in being a person of colour in the band" - Katherine Paul

“Even if I wasn’t the only person of colour in the band, the music they were writing just wasn't about race or wasn't about identity. It was just about whatever else there is in life. That wasn’t something that I really connected with, so I felt so good pursuing Black Belt Eagle Scout to fill that void. I play music and create the kind of music that has meaning to my life. I want to feel more connected, on a deeper level, on things that include my culture and identity. Those are the things closest to my heart that I want to sing about.”

Since living in Portland, she has found herself a snug community of queer creatives and musicians alongside her tight-knit family in her home tribe. In writing her follow-up, Paul began to think about how the most important relationships in her life formed a cohesive support network.

“I don't know where I was at the time, but this phrase just popped into my head. At the Party With my Brown Friends. I kept going with it,” explains Paul.

“I was like, that's a cool phrase. It can relate to like what I'm saying with this record and how important friendships are, especially within like communities of colour, and how important it is to like to support one another.”

"For me, at least, at parties, it’s about me always finding the brown people. It’s like, I know I’m going to be able to relate to you, and you’re going to be able to understand me.” - Katherine Paul

Some are separate, like the members of her family and those in her inner circle in Portland, but they are all linked to Paul. And so, in trying to weave together the family support tree, she began to reflect on her relationships in the metaphor of a house party. At the Party With My Brown Friends was born.

“My crew consists of mainly people of colour. So I started thinking: What does it mean to walk this Earth as a person of colour? What does it mean to me?” Paul says. “I started to think about parties. You know when you go to a party and it starts out okay, or it’s not that great, and things just get a little awkward, and all you want to do is find that one friend to make you feel better? The one you have a connection with? For me, at least, at parties, it’s about me always finding the brown people. It’s like, I know I’m going to be able to relate to you, and you’re going to be able to understand me.”

For Paul, finding her own community of like-minded people is immensely crucial to her. After leaving her tribe to move to Portland, being able to be around other queer and brown people was something that she needed to do. Luckily, in Portland, she was able to find a close-knit group of other queer musicians, but even in a city that is known for its inclusive and supportive DIY scene, she struggled to find other queer, non-white creatives.

Having been raised by an encouraging and nurturing family who she still is close to, and who supported her when she came out as queer, Paul needed to find a like-minded circle when she moved to Portland. Hailing from her tribe but living in a new city, she still finds herself struggling to balance her two identities as being a Native woman as well as a queer woman.

“I definitely feel caught sometimes,” says Paul. “Sometimes I feel more indigenous and I feel queer. Portland is one of the whitest cities in America. If you go to your queer community, the majority of it is going to be white. Some of the things that you want to talk about, like your culture… they’re just not going to know what you’re talking about. And sometimes you don't even feel like you can talk about it at all. Sometimes, in the queer culture here in Portland, I don't feel like I can actually be part of it, because people don’t get what it is to be indigenous.”

Eventually, however, Paul has managed to find a close circle of friends in Portland, despite being in the minority in her queer communities. Fabi Reyna, editor-in-chief and founder of She Shreds, a print publication that focuses on women and non-binary guitar players and bassists, is one of her best friends.

“I met Fabi at a Girls Rock camp in Portland about a decade ago, and we’ve been really good friends,” says Paul. Reyna, of course, is a huge part of the DIY and queer musician community in Portland through her music and activism. "She actually let me borrow her St. Vincent Ernie Ball Music Man guitar once, and I played it and fell in love with it,” Paul chuckles.

“I’ve been sort of like grappling with my identity lately what that means, and I think it has to do with not totally feeling accepted in a queer environment and. I'm trying to identify, in a certain way, as queer. But is there a better way that I can identify that doesn't have to be a part of white queerness?”

And so, At the Party With My Brown Friends is Paul’s love letter to the POC friends, family members, and people who are so important to her.

Being one of the few Native women in her creative circles in Portland, Paul feels more “other” in Oregon than she does when she goes back to visit her tribe. Despite being caught between two identities, Paul has never felt that she is an outsider when she returns to her family after so many years of living away from them – she only feels that she is an outsider in Portland.

“I don't feel othered when I visit my family no, I don’t think,” thinks Paul. “A lot of people tend to identify as two-spirits rather than just queer if they’re indigenous because it brings them closer to their culture.”

Paul’s relationship with her family, specifically with her mother, is a central theme on At the Party With My Brown Friends. “I have a great relationship with my family,” says Paul. "I know a lot of people don't. I know that if you're coming out and you're queer, it can be so hard.”

A track highlight is “You’re Me and I’m You,” a track that Paul penned specifically about her mother. A lot of songs written about mothers can be toxic, negative or reflective of their unsupportive relationship, but Paul’s bond with her mother – something special, and one that she doesn’t take for granted – is refreshing.

“ I feel like I want to be able to show what a supportive family is like, to give someone hope or something. That it can be okay to come out to your parents, and that parents can be okay with accepting their queer kids.” - Katherine Paul

“It’s about how much she loves me essentially,” she explains. “The title comes from the fact that I was a part of her. I was trying to find that that connection of love between mothers and children when it comes to coming out to your parents. I was thinking about how I was once a part of my mom, and the fact that our bodies were one would make her understand better. I know a lot of families who aren’t supportive. I feel like I want to be able to show what a supportive family is like, to give someone hope or something. That it can be okay to come out to your parents, and that parents can be okay with accepting their queer kids.”

Though it’s not as if Paul isn’t aware of what can happen when it all goes wrong with telling your parents that you are queer. “I’m not trying to say that yeah, everybody should have a great relationship with their moms,” admits Paul. “Some mothers are terrible. For me specifically, I had this positive experience with my mother. Hopefully, other indigenous people who are trying to come out have that experience and how it can be a positive thing. But maybe, if it isn’t, you can listen to this song and it’ll be healing.”

Though Paul admits that some Native American tribes can be conservative, it is from a religious standpoint.

Of the 71 countries around the world in which same-sex sexual relations are illegal, it's no coincidence that more than half are former British colonies or protectorates. The British Empire's has had a long legacy of homophobic legislation, so there was immense relief when in 2018 India’s Supreme Court legalised consensual gay sex. Homophobia is very much a colonialist legacy, and the world has had to deal with its repercussions.

“In my reservation, it seems like people are pretty accepting,” says Paul. “We're also like a teeny tiny reservation. There's like only a thousand people in our tribe, and everybody knows each. And because everybody knows each other, I feel like there's there tends to be like more connection between families and such. I know some people there on the in my reservation that identifies queer and they're totally accepted into our community, but I also know that there are some people in my reservation that are super religious.”

“Going to the Beach With Haley” is about fellow Portland-based musician Haley Heynderickx and a trip to the seaside the friends had together. “I met Haley through friends and we really connected,” laughs Paul. “We’re both Geminis! We were like, Geminis are twins. So you must be my twin. It's just about a day that we went to the beach together. We drove out to the coast with our little guitars and little keyboards and sat on the beach.”

Another track, “My Heart Dreams”, is one of the most lyrically intense songs on the record – “It’s just full of feelings” – Paul doesn’t find herself to be a natural lyricist.

“Lyrics are something that I feel like I would like to try out doing more, but the instruments come first. I'll be like playing guitar, and then I'll start singing something and then it'll sound good – and it just unravels from there.”

“I hope to make space for indigenous people at my shows. Land acknowledgments are the least we can do and in fact, we must do more.” - Katherine Paul

Ahead of her album release and tour, Paul has plans to release her own zine about the different indigenous groups across the United States to be handed out at her gigs. “For far too long, the music and entertainment industry has profited off of stolen land without giving back to native communities,” wrote Paul about her zine. “I hope to change that with making space for indigenous people at my shows, within my tours by being respectful and acknowledging those before us. Land acknowledgments are the least we can do - and in fact, we must do more.”

Paul had heard about Camp Cope inviting Sachem HawkStorm to the stage at Warsaw. As diverse as the music scene in New York is, land acknowledgments in the city don’t happen as one might think. Certainly in Camp Cope’s perspective – as Australians, they are extremely educated on the erasure of aboriginal tribes in their native country – they would have been surprised that what they were doing wasn’t, indeed, the norm.

During a tour with another Aussie musician Julia Jacklin earlier in the year, Paul would also say something about the place that she was playing to the crowd. “It took a lot of research on my part to figure that stuff out. But now, I feel like it’s just valuable information that people should be more aware of.”

Land acknowledgment is a chance for people to acknowledge, and pay respect, to the traditional owners and ongoing custodians of the land, which are the Native American and indigenous people. Land acknowledgments are often made at the start of an event, such as a meeting, speech or formal occasion. An acknowledgment can be made by anybody, indigenous or non-indigenous – though for Paul specifically, she stresses how important it is to actually have Native musicians in your band if you plan on doing a land acknowledgment.

While some individuals and cultural and educational institutions in the United States have adopted this custom, the vast majority have not. “Sometimes, white people have good intentions with making land acknowledgments, but it would just be more powerful to have a Native person to do it. They need to be able to create the space for indigenous people to share their art on their own land,” asserts Paul.

Land acknowledgment is a relatively small gesture to make, but it is powerful in its approach when it is tangential to authentic relationship and informed action. Land acknowledgment not only raises awareness to the general public about Native rights, but it is also an important step to reconciliation.

“I regret when I do it at the beginning of a show because I’m concerned about those who come later and miss it,” says Paul. “I just wish more people knew about it. The idea for the zine is to have some material to have people learn from.”

Specifically, the zine will list all of Paul’s tour dates as Black Belt Eagle Scout across the United States coupled with her own research about the areas, as well as some areas for people in those cities to help indigenous people.

“I really want to bring people into the show more, and to kind of have people be respectful to the land. They might not even know what’s going on, but I just hope that in doing so, they learn more about the land they’re living on so they can connect and create action,” continues Paul.

“These land acknowledgments are the tiniest things we can do, but hopefully, it will help spark fire to create more awareness. I want more prosperity for indigenous people because their lives have been so affected by colonisation,” she says, finally. “And, if white people are going to invite someone to do their land acknowledgment, pay them.”

National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center

The National Indigenous Women's Resource Center, Inc. (NIWRC) is a Native nonprofit organization that was created specifically to serve as the National Indian Resource Center (NIRC) Addressing Domestic Violence and Safety for Indian Women. Under this grant project and in compliance with statutory requirements, the NIWRC will seek to enhance the capacity of American Indian and Alaska Native (Native) tribes, Native Hawaiians, and Tribal and Native Hawaiian organizations to respond to domestic violence. You can donate here.

Urban Indian Health Institute

Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) is leading the way in research and data for urban American Indian and Alaska Native communities. As a Public Health Authority and one of 12 Tribal Epidemiology Centers in the country—and the only one that serves Urban Indian Health Programs nationwide—UIHI conducts research and evaluation, collects and analyses data, and provides disease surveillance to strengthen the health of American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex