Frontman Alex Kapranos takes us on a powerful tour of strangely uplifting melancholia

"When I was putting this together, I was trying to create a mood, rather than just picking any old songs that I'd listened to at certain times in my life."

Particularly, Alex Kapranos was looking to cultivate a feeling of melancholy with these songs, a mindset he readily admits might not be one that casual fans of Franz Ferdinand would associate with him. "Passing listeners to the band might not expect that from us," he says, "but people with a deeper knowledge of what we write would recognise it instantly." He reels off a list of deep cuts from across his group's catalogue to prove his point, including '40', 'Fade Together', 'Katherine Kiss Me', 'Little Guy from the Suburbs' and 'Slow Don't Kill Me Slow'.

Similarly, only one of the nine tracks he's selected here was a single; the rest are plucked from albums, radio sessions and - in one case - an old demo tape. Some of the choices fall close to home for Kapranos, from a very early incarnation of old friends and fellow Glaswegians Belle and Sebastian to Edinburgh miserabilists Country Teasers. Others meanwhile, are separated from him by time and place, but no less emotionally resonant.

"For me, the holy grail of songwriting is to create a genuine melancholia, but one that's simultaneously completely uplifting," he explains. "I have tingles running through my veins just thinking about these songs and the way that they make me feel. I could talk about the stories behind them, what they meant to me at particular points in my life, the history of the musicians or the technique in their writing, but to be honest, it's all incidental. The reason I love these songs is because they make me feel a particular way. That’s what I’m always searching for.”

“O Horos Tou Sifaka” by Yiannis Markopoulos

“My dad’s Greek and he came to Britain when he was nine or ten. Like a lot of people, he used music to maintain his identity and when I was a kid, he used to play a lot of the stuff that he brought with him - everything from contemporary rock to older folk and then Yannis Markopoulos as well. He’s one of Greece’s foremost composers. He’s from Crete and he sort of interpolates melodies and rhythms in a way that’s thousands of years old really.

“This particular song has a real resonance for me, because it’s probably the first piece of music I can remember the experience of listening to. My dad used to put it on when I was two or three years old and he’d put me on his shoulders and spin me around. It’s incredibly hypnotic and repetitive and I remember this amazing sensation of the first time I had that feeling of music moving me beyond the state of resting existence. It’s stuck with me and I can still put it on and get chills from it - partly because it’s a very powerful piece of music anyway, and partly because it has that incredible memory attached for me as well.

“Greek music is still a big part of my life. A few years ago I was involved in this performance at the Barbican where various musicians got together to perform the music and tell the story of another Greek composer, Markos Vamvakaris, and I was the narrator. I joined the rest of the musicians to sing with them at the end of the show and it was a great moment for me. When you’re a generation removed it’s tougher to stay in touch with your national identity, you have to put a little bit more effort in to appreciate your history and your heritage, but it’s worth it.”

“Sonny’s Lettah (Anti-sus poem)” by Linton Kwesi Johnson

“I believe this track had a lot of political resonance in the late ‘70s. I don’t know what the impact was at the time, because I was too young - I would’ve been about seven years old. It’s so articulate and compelling; it’s one of the most powerful pieces of lyricism to have come out of the twentieth century.

“One of the biggest clichés that I despise is when guys who write lyrics for their band describe themselves as poets - it’s usually the most absurd affectation. With Linton Kwesi Johnson though, you have the opposite, a genuine poet who is putting his words to music. It’s really powerful sonically, too - Dennis Bovell’s production is astonishing and the record just really kicks. The words aren’t just believable, but completely empathetic. When he’s describing blows raining down on his friend and his reaction, it’s like you’re there with him. It’s like stepping into a movie or a really good book and watching the hero right in front of you. Very few songs pull that off as well as this one does.

“I’d always listened to reggae growing up, but I didn’t hear this song until I was nineteen or twenty. I shared a flat, for a long time, with a guy from Ghana who was a big Linton Kwesi fan, and it was him who played me the record first. When I was growing up in the ‘80s, the Afro-Caribbean community in Britain didn’t really have much of a voice in the general media, so this record still felt relevant ten or fifteen years later when I finally heard it.

“I was just talking to my sister the other day about the racism we saw going on at school. We went to the same one, this really ordinary comprehensive in Glasgow, she’s ten years younger than me and yet we saw similar things. It wasn’t even casual racism - it was often really active racism through which people identified themselves. There were school desks with NF scrawled on them, and some of the language that was thrown about was pretty appalling. It made this song all the more powerful when I first discovered it.”

“Le Pastie De La Bourgeoisie” by Lisa Helps The Blind

“Lisa Helps the Blind were Belle and Sebastian before they were Belle and Sebastian, a very early incarnation of the band when it was mainly the two Stuarts - Murdoch and David. I used to put on bands at this place in Glasgow called The 13th Note, there’d be a Tuesday night where anybody could play and then a Thursday night for groups who maybe were a little bit more together.

“Stuart Murdoch came down a couple of times and he’d sometimes play at acoustic nights there too. I think I put on one show when they were still Lisa Helps the Blind. What I remember more than anything else was how quietly Stuart would sing, to the point that you could barely hear him over the general level of chatter in the room. I think he was very frustrated at the time, because it wasn’t in his nature to make a scene and force people to listen; he wanted them to pay attention because they appreciated the songs, you know? He was clearly a great melodic songwriter, but that track especially...

“I’ve got that demo tape somewhere, in a box and it’s been there for the last two or three times I’ve moved house. I wish I could find the bloody thing because I love that version of the song. It’s quite different from the Belle and Sebastian recording that came out later, on the 3...6...9 Seconds of Light EP. I don’t want to diss that version, but the Lisa Helps the Blind one was slower and felt a little bit more lovingly crafted. I just thought, ‘Whoa, there’s something special going on here with this guy and his writing.’

“The lyrics weren’t like anything I’d heard before - the imagery he was using was both extremely profound and extremely non-rock and roll, this song from the perspective of a guy who’s going to church and fantasising about this rather plain-looking girl who is resenting being in church herself. I fell in love with the quirkiness and contrariness of it, but there was also a quiet self-assurance to it that I’ve admired about Stuart ever since.

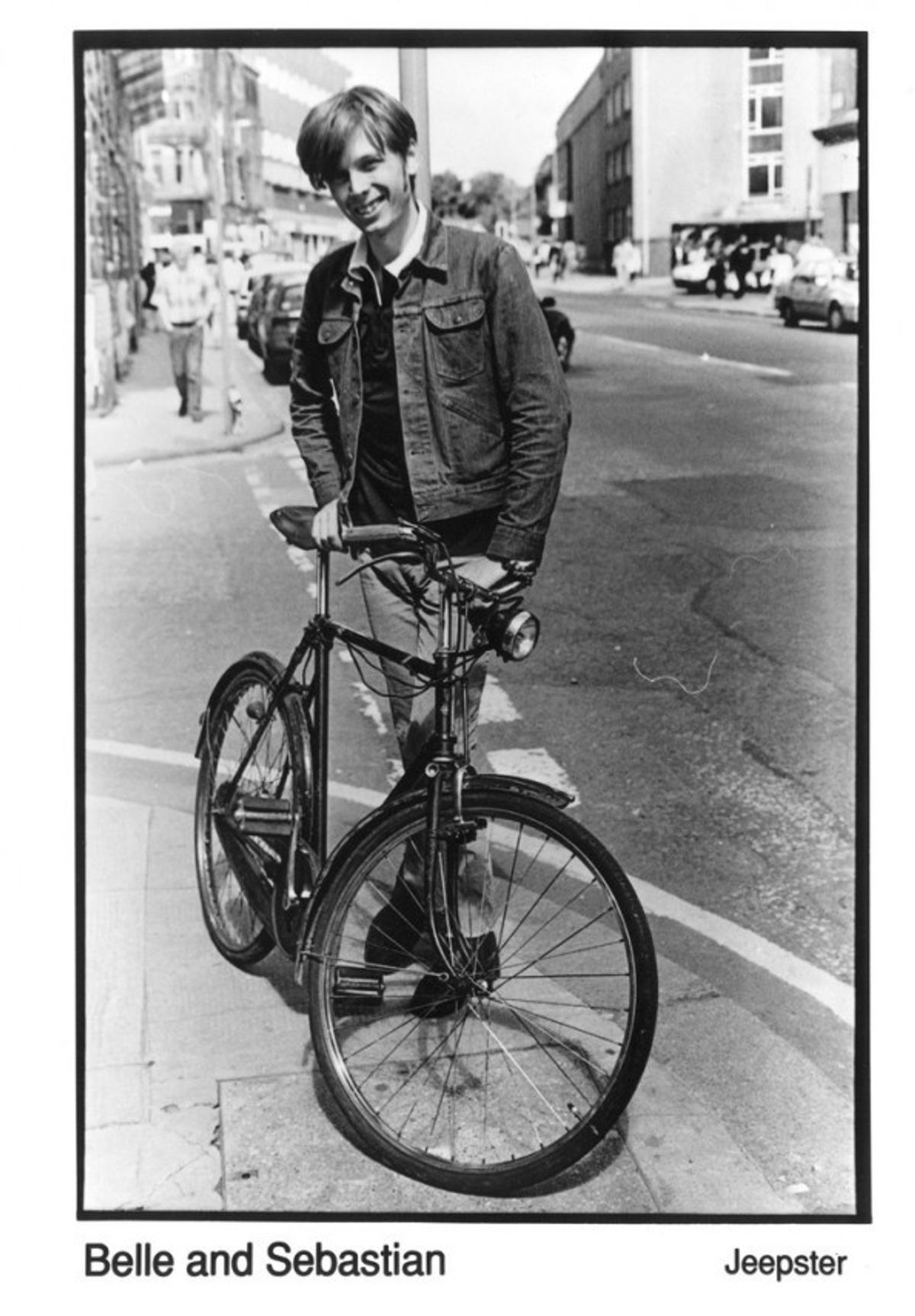

“I was in one of Belle and Sebastian’s early press photos too, they didn’t appear in them themselves in those early days. That was a very specific time in 1996, after Tigermilk and before If You’re Feeling Sinister. Stuart just stopped me on Byres Road one day, when I was out on my bike. I look so chuffed, because I loved that bike more than anything else in the world. I took a train out to Helensburgh and bought it from this guy who’d bought it new in 1948 and cycled to work on it every day of his life until he retired. It was this really heavy, beautiful old Raleigh.

“I was away on tour one time and the landlady of my flat on Bank Street in Glasgow cleared out the garage and she chucked it out. It was so heart-breaking! Anyway, the photo is from a period when the band were being bashful but also playing games with the press at the same time, which was funny. Stuart was a great photographer, you’d always see him around town with his camera.”

“Golden Apples” by Country Teasers

“From one extreme to the other. Belle and Sebastian were one side of what was happening in Glasgow, and Scotland, in the ‘90s when I was really young and just starting out and to me Country Teasers represent another parallel, a much darker and more sinister side of what was going on.

“They came out of Edinburgh, where they were all from, apart from Ben Wallers, the singer, who’s English. They’re another band I put on in The 13th Note and another band I was drawn to both sonically and lyrically. As you’ll know if you’ve heard this record, Destroy All Human Life, some of the lyrics are extremely difficult. Ben’s attitude has always been to try to make people as uncomfortable as they possibly can be and to explore issues that are usually not talked about at all.

“This song, weirdly, I find to be quite beautiful; the melodic line is really wistful and melancholic, which as I said, is what I was aiming for with this collection of songs. There’s a sort of perverse humour to this particular track too. That’s what makes it all the more vivid for me; he’s talking about his bandmates, who I can picture because I knew all those characters at the time.

“He rips into them mercilessly! He’s saying Richie’s so weak he almost can’t be seen and something about Eck being skinny and Alan, the guitarist, having a big hook nose. Simon, I think, he said had funny feet and then at the end, he says, “I am the perfect image of mankind / Made by god to remind him of his son / My back is straight like a straight white line / Golden apples issue from the hole in my bum.” It’s really fucking funny!

“And also, it captures a particular sense of humour that was shared by a lot of people I hung out with in Scotland at that time and still do. It’s quite dark and sadistic.”

“Lady Rachel” (Alan Black Session) by Kevin Ayers

“I’ve always had a soft spot for those artists that came out of the sort of psych-folk scene in Canterbury in the late ‘60s, but of all those performers Kevin Ayers is probably my favourite.

“‘Lady Rachel’ has a real Englishness about it, which is kind of alien and almost exotic to me, because it’s a place I don’t really know much about; I never lived there. There’s something so far removed about the way he sings and pronounces words, like he’s from some far-off land. It feels like it’s come from the world of King Arthur and Alice in Wonderland and maybe a little bit of Mary Shelley or something. It’s a little bit Victorian and again, the themes are dark - it suggests death in the water. I liked that section of the ‘60s, where the psychedelic stuff was becoming a little bit more playful and wacky.

“I don’t know about you, but sometimes I get really obsessed with songs and hunt down every version I can find of it. With ‘Lady Rachel’ I always felt like no one take of the song completely captured everything that was good about it; instead, each version captures one element of what I loved about it. The one that ended up on the album, Joy of a Toy, is really full and rich and very produced, but it’s played too fast and it loses a bit of the suspense - that glittery other-worldliness that gets lost in the speed of the performance.

“There’s an amazing rendition of it that he did on The John Peel Show in 1973. Again, it’s a really beautiful version but there’s just this one line where he kind of steps out of character - he says “at least not very much!” in this kind of dorky, jokey voice and it undermines the mood of the rest of the song. It’s like going to see a play, getting to a critical moment and then the lead actor turns to the audience and says, ‘Hey, everyone - I’m actually just an actor.’ I’m always going, “Oh, man! Why did you do that?” Anyway, what the fuck am I doing, chasing perfection in music?”

“Tears In The Typing Pool” by Broadcast

“Even just thinking about this song, I can feel the beginning of tears in the backs of my eyes. It's such an astonishing piece of lyric writing. It's like that Linton Kwesi Johnson track - the narrator of the song, and their emotions, are so believable. Both songs are about letters, funnily enough.

“The imagery is so gentle but it's still significant and it's recognisable of a different world; just the idea of a typing pool now is absurd - it's something that belongs to a different decade. And then the imagery of the paper and the ink drying and there's a confession, but we don't know what the truth is. She's talking about telling the truth in this letter she's written, but we don't know whether she's confessing to something she's done or to the way she truly feels.

“Either way, it's definitely a story about the end. 99.999% of people who've loved in their lives will know how that feels, what it's like when love ends and this is one of those songs that just gently captures the hugeness of that kind of situation. It's sung and worded very softly, but what it's describing is incomprehensibly massive. It's communicated with that image of the page being wiped clean, while the landscape remains unchanged. Absolutely astonishing.

“Trish Keenan’s death is a story of tragedy in itself, because she was so unique. I know you shouldn't try to relate the personal story of the performer to the piece of music, or the writing, or the play, but you can't help but do it in this case because so many Broadcast songs are in that vein. When you communicate emotion in a song the reason it works is because, as a listener, you recognise something you've experienced before, and so Trish's writing doesn't just remind you of loss - it reminds you of the loss of her.”

“To The East” by Electrelane

“I'm just realising as we're going through them - so many of these songs are about loss aren't they? ‘To the East’ isn’t just straight-up melancholy, it’s a song of hope as well; it might be completely redundant, impotent hope, but there is still hope in there.

“She's singing to somebody to come back and that the East could be home, but the whole time you're listening to it you suspect the truth of the situation is that those words will never actually be said. Or maybe that's just the way I'm feeling it, I don't know. Again though, it's a very easy song to empathise with; I really believe the voice that's singing it to me. I don't know whether it's about a personal experience or if they're just imagined characters and to be honest, I don't care. I'm right there with them - I'm feeling it too.

“I think either our first or second ever show outside of Britain - I can't remember which - was with Electrelane, in Barcelona at that club, Razzmatazz. It was quite the thrill, to be leaving the country to open up for this band we loved. I was really sad when they split up - again, another loss. I wish they were still performing. I think the last time I saw them was at Field Day in 2011 and they were still so great. They did a cover of 'I'm on Fire' by Bruce Springsteen and it was really something else.

“They're one of those bands where you only need to hear a few seconds of any given song to know it's them, which means they've also got that trick of being able to make a cover sound like they wrote it themselves.”

“The Lowlands Of Holland” by Steeleye Span

“This one's not quite as contemporary as Electrelane – in fact, that's putting it mildly! It's an old folk song that dates back to the seventeenth century, so it's been passed down through the generations.

“This is the version that fits the mood of this collection of songs the best I think. It's another one about losing somebody; it's about a young woman who's lover has been kidnapped by a press gang and taken out to sea and she's not going to see him again - it's a terrible, terrible tragedy.

“Steeleye Span are a funny band; they came out of a scene that's not too far removed from Kevin Ayers and that electric folk movement of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. They evolved into something that perhaps wasn't so cool later on - there's a record called All Around My Hat that's a bit Alan Partridge - but those early albums are really great.

“I definitely have a personal connection to ‘The Lowlands of Holland’. It's an unusual song, actually, in that I can never figure out whether it's Scottish or Irish in origin. It doesn't really matter, but it has significance for me because I live and have my studio in Dumfries and Galloway, and in the song, Gabe Woods is singing about the man from Galloway.

“So I imagine it's where I am and when I'm hundreds or thousands of miles away from home, I hear that song and I imagine being back in Scotland. It generates a degree of homesickness and wistfulness and it's good to feel that, because it reminds you of what home is, and why you should return there.”

“Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” by Paul Robeson

“There's a reason that I left this one for last. I put it in this position because it seemed like the natural conclusion to this collection of songs. It's the climax, it's the one that gathers everything up and then sums everything up emotionally. It's the finale - everything's building up to this moment. There's centuries of pain, tragedy and - again - loss in his voice, it's undeniable.

“The lyrics are based around one extremely simple metaphor, but so much that's good in art, whether we're talking about visual art or songwriting or performance art or literature or poetry, so much that's truly powerful takes one easily understood idea and then brings depth to it. That's what's happening here - it's a metaphor that you instantly understand. It's like looking at a Picasso painting; you're immediately struck by the image, but there's so much more going on beneath the surface. You can listen to it hundreds of times and not feel as if you've exhausted its emotional content.

“We were talking about Trish Keenan earlier, but she seems like one of the exceptions to the rule I subscribe to, which is that you should be able to understand everything purely from the performance and the lyrics. You shouldn't need to know anything about the artist's personal life. Paul Robeson was this gargantuan figure of the twentieth century; there was that intelligence, integrity and, for the most part, nobility to him, going as he did from singer to actor to petitioning the President of the United States, but you wouldn't even have to know the slightest thing about him, and you'd still have that instant reaction to this song; there's so much emotional power to it.

“I don't know how I'd deal with life if I didn't have music like this - to help me go through it, and to help me understand it.”

Always Ascending is out now via Domino

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Tunde Adebimpe

Thee Black Boltz

Julien Baker & TORRES

Send A Prayer My Way

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE