The Rebirth of Fenne Lily

As she recounts the unhealthy relationships, the imposter syndrome and the intense conversations with those closest to her, it strikes me that Lily's second record didn’t come easily. After a month of self-enforced solitude, a broken phone and a lot of self-reflection, BREACH is finally here: and it’s her boldest and most intricate work to date.

It also becomes apparent when we speak one Friday afternoon, that Fenne Lily is as down-to-earth as her music: sincere, with a wry, self-deprecating sense of humour, and a story to tell about everything.

“I've been excited to release a second record since the day I released my first,” says Lily. “It’s a chance to update the way people see me, and the way I see myself too - a bit like getting a new passport picture when the old one was taken when you were fifteen.” BREACH follows Dorset-born Lily’s acclaimed debut LP On Hold, self-released in 2018 - a collection of sleepy love songs penned in her teens. Although she had older songs from that time reserved for a second album, the now 23-year-old found that she was writing faster than ever, meaning that BREACH consists entirely of new stories and experiences.

Her recent signing to Dead Oceans, alongside the likes of Phoebe Bridgers and Khruangbin, was particularly significant for Lily, who grew up admiring the label. “When I was 16, I worked in a tiny record shop in Dorset, and sometimes I was allowed to pick the records that they sold in the shop. I’d basically just go on Jagjaguwar, Secretly Canadian or Dead Oceans' website and pick whatever they had released, because I knew it would be up my street.

“It's nerve-wracking being on a label this time,” she admits. “I think the expectation for the record to be good is higher. People will look at me and think ‘she’s labelmates with Mitski - how does she compare?!’ But saying that, I don’t think reviews and what people think should have to validate your art.”

Lily and her team worked on the record right up until the lockdown was announced, with most of the musical elements finished just in time. With a summer tour with Waxahatchee cancelled, Lily spent the lockdown laying low in Bristol, counting her blessings. “It's been actually quite nice for me - a good opportunity to do more reading, write to people that I haven't spoken to in a while. I've planted salad and played a lot of online pool on Mini Clip, which is not something I'm proud of, but I don’t seem to be able to stop. You play against strangers and you can trash talk them. I have a couple of marriage proposals from it.” She trails off and, with an almost audible eye roll, concludes, “I wish I could be one of those people who’s like ‘I finally got a skincare routine and I've written a book!’”

BREACH itself was born of a period of solitude, unrelated to the isolating existence of the forthcoming pandemic. In a pre-coronavirus world, Lily was finishing up her European tour when she was struck with an overwhelming desire to not go home. She booked a flight to Berlin, got in touch with a friend who lives there, and checked herself into an Airbnb. “I wanted to see how I dealt with not having anybody around apart from myself. Everything was feeling temporary - I had become very used to doing things like going on dates and then being able to leave the situation because we had to drive out the next day. I was feeling like I’d lost my sense of self a bit. I wanted a break from being ‘Fenne Lily’.

“For the first couple of days, I was scared and I didn’t leave the house. But my friend got me a guitar; I did a lot of walking, read a lot of books, and listened to Harrison Whitford’s record Afraid of Everything pretty much daily.”

Her time in the city came to represent a kind of rebirth, proof that she could be self-sufficient even amidst the turbulence of life. The experience solidifies itself in the single, “Berlin”, on which Lily muses the messiness of solitude and learns to live with her restlessness. “It’s not hard to be alone anymore,” she sings, “Though I’m sleeping with my key in the door.”

‘Goes to Berlin once, writes a song about it,’ she joked on Twitter on the day the single was released. On why she chose Berlin as the scene of her seclusion, Fenne says, “It just seemed like the kind of place where people wouldn't bullshit me. The people there seemed more on my wavelength, like what they hold in higher importance is more in line with what I agree with. It's just really cool. And you don’t get funny looks if you walk around dressed in black.”

Making a conscious effort to live in the moment, Lily separated herself from “insidious” social media, just using her phone for recording notes and sketches of songs. “And then on the plane home,” she sighs, “my phone died and I lost everything. It was awful. I normally pride myself on having like a pen and paper all the time - I'm like an old person in that respect - but in Berlin I just trusted my phone.”

Back in the UK, Lily’s next few months were spent trying to piece together her ideas from memory. What followed was a kind of redraft: some songs were recalled with ease, some were fragments which she merged together; others were likely lost forever. In a parallel universe, one where her phone had held itself together, BREACH could have been something entirely different - but as infuriating as it was at the time, Lily manages to look back on this disruption in her usual process as a blessing in disguise. “It was a lesson in allowing things that should be remembered to be remembered, and not feeling like I needed to use everything that I'd made. I think it's testament to the strength of what I did remember that it had stayed in my head.”

Musically, touring and learning to use recording software brought new depth to Lily’s songwriting, allowing BREACH to be Lily’s farthest reaching and most sonically expansive work yet. Largely recorded with a full-band, the intricacy and slickness of the arrangements create a beautiful dissonance with the fragility of Lily’s signature husky, whisper-like vocals. From its ethereal beginning, BREACH feels like a journey: emotionally turbulent and raw; somewhere between tentative and assured.

On BREACH, Lily is figuring herself out in her own time; leaving all of her workings in, no matter how messy they may be. “Remember to forget,” she sings on the gorgeous, hushed ballad ‘Elliott”, “Everyone you ever wanted to be / Is dying the same death.” Imposter syndrome, and feeling wrong about things going well, are strong themes throughout the record. “It can be difficult to talk about those feelings,” says Lily, “because obviously I’m so lucky to be able to go on tour and to do what I want to do. But it can be draining to take yourself back to that place emotionally. The difficulty that I have expressing myself and feeling everything all the time - it’s not something that I have to do by myself. I constantly remind myself that everyone I admire has felt the same way.”

Lyrically, too, Lily’s approach has evolved with her taste and experience. “With On Hold, I was really concerned putting words together in a way that kind of clouded the truth - diluting the meaning so that other people could apply their own experiences to it. But when I was writing this record, I was consuming a lot of stream-of-consciousness, less metaphor-based work. I was reading Richard Brautigan, and touring with Lucy Dacus influenced me a lot. That’s also partly why I love country music - you get a story and by the end of it, there's a solution. It’s a bit like watching a film in three minutes.”

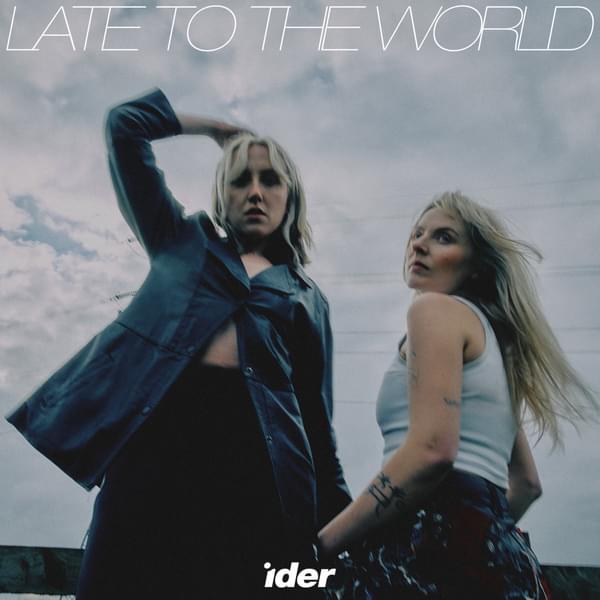

"There are so many album covers that I love but I don't know why, but when it comes to getting ideas together for my own, I'm blank."

On the record’s cover, Lily sits slumped against a yellowing storage heater, looking absent-mindedly to her right and anxiously pulling her jumper up to cover her face. As the best album covers do, it seems to capture the record and epitomise its spirit: vulnerable and intimate, yet quietly confident. “Album artwork is always a problem for me,” says Lily. “There are so many album covers that I love but I don't know why, but when it comes to getting ideas together for my own, I'm blank. I started by knowing what photographer I wanted to work with.”

That photographer was Nicole Loucaides, with whom Lily bonded in unusual circumstances. “Nicole was on a date with one of my friends, and we realised that the guy I was sleeping with at the time was her ex-boyfriend. She kind of warned me about him, and that precipitated the end of whatever was going on. I felt like Nicole and I working together would be cool: a bit of a middle finger to this dude, and to other dudes that are shit to women.”

Lily continues, “I often think that it's sad that society has made women feel like they need to compete, either for men or for success or whatever. It feels that there's less of a space for women sometimes than there is for men, and we have to claw your way to a position where you're taken seriously.” Lily’s rejection of such toxic, heteronormative standards feeds into the lyricism of BREACH, in particular on the the lilting country ballad, "I Used To Hate My Body But Now I Just Hate You". When exploring sex and relationships through her songwriting, Lily adopted the approach of turning the lens onto herself, documenting her own growth from the situations she found herself in rather than the person or situation that hurt her. “With On Hold, I wasn't very angry about the relationship I was writing about, because I understood why it ended and I respect the person who broke my heart. With the experiences I’m talking about on this record, I didn't have the same experience - it was very much a situation where I could be angry about it. I didn't try to hide that.”

With BREACH, Lily scrutinises and documents her past, her present and everything in between, all the way back to her literal birth. The record’s title merges the word ‘breach’, representing Lily’s breaking down of personal barriers, and a reference to her own breech birth. Conversations with her mother offered insight into the lasting effect of her traumatic first moments. “The way I came into the world has informed the way that I see things. I was in physical pain for the first year of my life - a lot of things had to be realigned. I apparently cried for six months after I was born; I would only stop crying if I was being held... which has kind of stayed the same!

“I think there's definitely something to be said for inheriting pain. Things that happened to my parents before they had me have informed how I live my life, and given me a distrust for certain people or things. The more I speak to my parents about their lives, the more I understand myself.”

Going all the way back to why she writes music in the first place, Lily describes the process as cathartic: in both her own experience of creating, and in witnessing the solace that the music provides to her listeners. “Therepy has never been a great option for me,” she explains, “because I either close up or I open up so much that I feel stupid. So writing is a helpful middle ground - being able to pour out my own thoughts and problems into a format that people can relate to, and then to hear how I might have helped them, or made them feel less alone.”

She cringes slightly at herself, and insists that she doesn’t have a saviour complex. “From my perspective… it’s a bit like being sick and then framing it.”

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Great Grandpa

Patience, Moonbeam

Deafheaven

Lonely People With Power

Perfume Genius

Glory