Chicago-based shoegazers Slow Pulp are overcoming their personal obstacles

“Montana” was a critical turning point for Slow Pulp. Written for Moveys, their self-produced full-length debut, the track revealed itself to be “super different from any other song we’ve written,” says bassist Alex Leeds, signaling a seismic shift in the band’s approach to the album.

Downtempo and driven by acoustic chords, the song’s slide guitar and harmonica accents lend it a rustic, isolated feel befitting the wide open spaces of its namesake. But more importantly, the folksy expanses of “Montana,” the first Moveys track to take shape, gave Slow Pulp permission to wander and explore—as Leeds explains, “it opened up the field of what this record was going to be.”

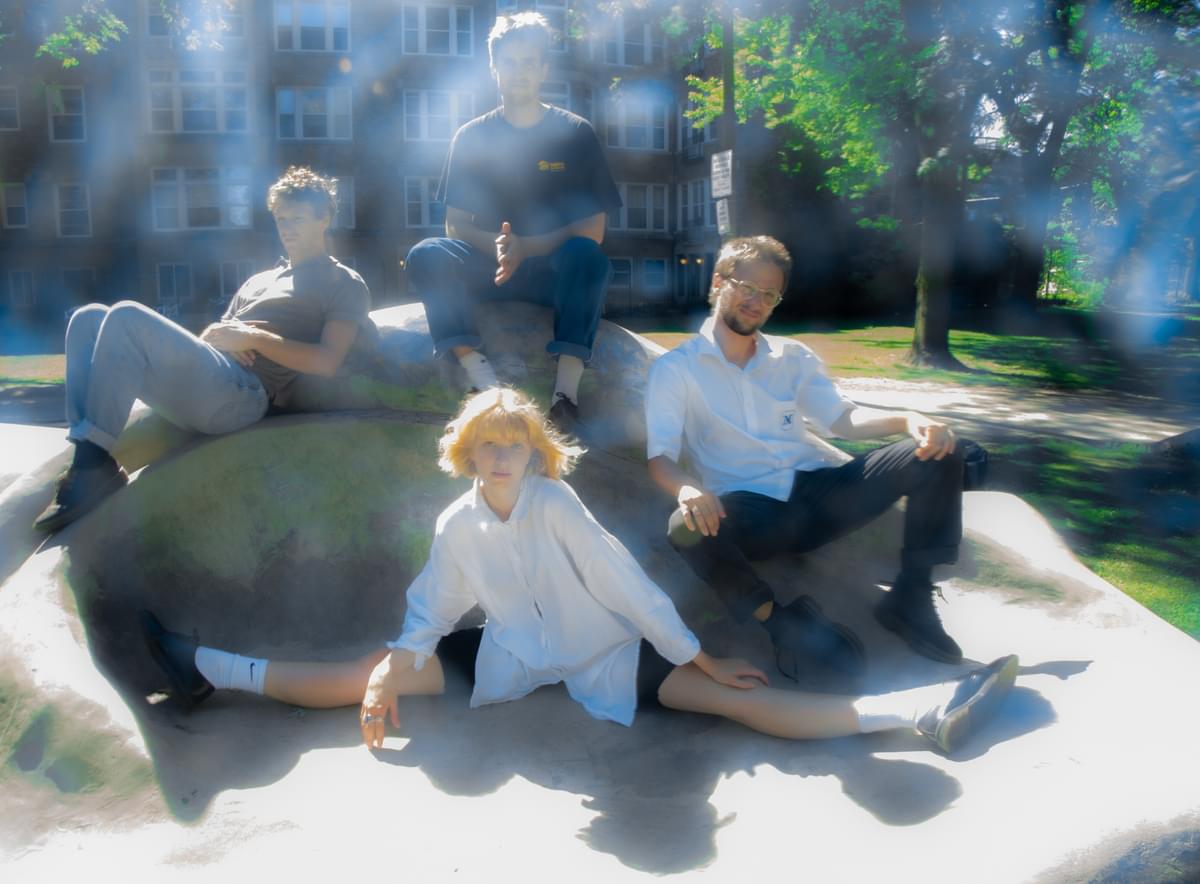

One could be forgiven for expecting Moveys to hew more closely to shoegaze and post-punk sounds, as Slow Pulp have in the past. On 2017’s EP2 and last year’s acclaimed Big Day, the band delivered nervy, innovative rock that blended elements of those and other subgenres, with unshakeable melodies and unpredictable arrangements. Their sound is rooted in the friendship between Leeds, drummer Teddy Mathews and guitarist Henry Stoehr, which dates back to their elementary school days in Madison, Wisconsin. “I feel like when I joined the band and when I became friends with you guys, I learned another language,” vocalist/guitarist Emily Massey recalls with a laugh.

The band, who’ve since relocated from Madison to Chicago, leaned on each other en route to their full-length debut, which was beset by both creative and personal obstacles. They started work on new material right shortly after Big Day’s release, setting their sights on an album, but something just wasn’t clicking. ”We hit a point where everything we had done up until that point was just not… I guess personally, I was starting to feel emotionally distant, because some of the ideas were starting to feel pretty old, and we weren’t necessarily landing them, you know?” says Stoehr. “They were just kind of floating.”

Helping to ground them was a frequently fatigued Massey’s diagnosis with Lyme disease and chronic Mono, which she has said “validated a lot of what I was feeling,” forcing her to confront both her physical and mental health via her songwriting. Something shook loose while Slow Pulp was on the road with Alex G last fall: “At a certain point, I feel like it shifted, and we started new songs, and then we just accelerated in that process, and that’s the album that turned out,” says Stoehr. “But it definitely felt like there was a clicking point where we found the groove with a couple of the first songs on this album and just went from there.”

Foremost among those songs were the aforementioned “Montana” and tone-setting album opener “New Horse,” both of which foreground the acoustic guitar—Massey calls the instrument “a leading force” on the album that “none of us expected,” explaining, “I think that opened up a lot of things for us. I had also been listening to a lot of folk music at that time, listening to a lot of Neil Young, Joni Mitchell and Jessica Pratt, and just guitar and vocals. And I think that naturally came out. It felt easier to write emotionally driven songs based on that format.” Moveys isn’t dominated by this stripped-down sound—“It’s got undertones,” Stoehr deadpans—but those undertones certainly enrich the album’s emotional texture, adding a striking new color to Slow Pulp’s palette.

But their renewed creative momentum was met with another destabilizing personal blow. In March, as Slow Pulp were finishing the album, Massey’s parents were in a serious car accident, calling her home to Madison to care for them—soon after, COVID-19 began spreading in the US, meaning Massey and her bandmates had to finish Moveys from a distance. Fortunately, they had experience in bridging such a gap: “We’ve always had our own music spaces and done a lot independently,” says Leeds.

“Even when we all lived together last year, the first year we moved to Chicago—even then, when we were in the same space all the time, somebody would send me an MP3 of a song and I would still work on it by myself, in my room,” Massey recalls. “So it was already this [act of] sending things back and forth that became a part of our process that just works for us. It didn’t have to change much when we were quarantined apart from each other.”

While the means of working was familiar, the making of Moveys required Slow Pulp to take a hard look at their songwriting process, with Stoehr, Leeds and Mathews better integrating Massey into their longstanding dynamic by “figuring out the order of operations,” as Stoehr puts it. They shifted from “writing full live-band stuff at practice together” to “someone having a chord progression and that getting passed to Emily earlier on in the process,” Mathews explains. “We had been writing almost full instrumental songs, and then trying to have Emily work within those... we didn’t realize at the time that wasn’t really working for us,” says Stoehr.

Slow Pulp’s kinship enabled them to keep pushing until they broke through: “I think there’s a lot of things that clicked at once, both personally and within the band,” says Massey, who worked with Stoehr to get the album in on time. The pandemic actually had a positive effect on the record in that regard: “We had a pretty tight deadline towards the end there,” Mathews notes, but between the cancellation of South by Southwest and Slow Pulp’s subsequent tour, and Stoehr being laid off from his job, that extra time proved crucial to the album’s completion. It also forced Massey to reckon with her experiences along the way: “There was no time to process a lot of what I was going through. And so in a way, the songs became that processing.”

Moveys had every excuse to be a mess, and it’s a testament to Slow Pulp’s unity that the album is anything but. Streamlining their songwriting process equipped them to branch out and explore unexpected avenues, like the forlorn folk of “Montana,” with slide guitar and harmonica from Willie Christianson, or the dreamy fingerpicking and synth atmospherics of “New Horse,” which Massey calls “the first song in a long time that I had worked on and was proud of.”

They wield what sounds like synthesized slap bass on “Trade It,” while Alex G collaborator Molly Germer contributes keening violin to “Falling Apart.” The moments more in line with past Slow Pulp releases land just as well, from the shoegaze buzz of “Channel 2,” featuring Leeds on lead vocals, and “Track,” with its hushed vocals and a reverb-heavy riff that would make Big Thief blush, to the intoxicating guitars of lead single “Idaho,” and the pop-punk crunch and cooed hooks of “At It Again”.

The album's variety will likely buck listener expectations—it certainly did Slow Pulp’s own. “We set out to make something pretty heavy,” Stoehr recalls. “And once it started, it was like, ‘This is not gonna be like that.’ It all felt really natural the way that stuff came together, but it was definitely not what we were imagining at the beginning.”

Leeds agrees, adding, “The whole thing was kind of a surprise. It was all very unclear what it was gonna be, right up until the end.” That sense of adventure made all the difference: “There are parts of making a record that can be really tedious and really difficult, and the ways that we surprised ourselves was what made it exciting and made us want to continue to work on it,” says Massey.

The album’s making was not only a creative challenge, but also a means of coping. For Massey, it meant collaborating with her father Michael, also a working musician, as he recovered from the physical trauma of his accident. “Our relationship is very unique in that sense, that we share this career path,” says Massey. “But we hadn’t really worked together like that before... He was recovering from some pretty serious injuries and it allowed him not to think about it. And it allowed me not to think about it, and it was like this little break of working towards something that had an end goal.”

Central to that goal was “Whispers (In the Outfield),” a lovely piano instrumental penned by Stoehr and performed by Michael Massey. “I think that took him out of his comfort zone in a lot of ways,” says Massey. “And it was the first piece he played after the accident. He hadn’t played at all until then.”

Slow Pulp are hesitant to suggest what meaning listeners may find in Moveys, but receptive to the idea others may share in its catharsis. As a new level of collective trauma washes over the world, these songs offer a path forward, finding “a sense of lightness and playfulness even though it’s dealing with serious things,” as Massey observes. But that path is just that: a journey, rather than a destination. “There’s an innate piece of us that, kind of, we have to keep pushing forward. Moving, growing, learning, living,” Massey says of facing adversity. “It’s not like, ‘I’ve made it, I’m here.’ The whole record is a process of getting to somewhere that you want to be.”

For Slow Pulp, that next somewhere is back to work: “I’m excited to make another one. I think we’re starting to gear up to do it again,” says Massey. “The second album is hopefully just gonna be even more realizations and learning, and ways that we learn that we can work together.” As the lessons pile up, one imagines there are more “Montana” moments ahead. Here’s to the next adventure.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Tunde Adebimpe

Thee Black Boltz

Julien Baker & TORRES

Send A Prayer My Way

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE