Shirley Collins' Personal Best

The inspiring renaissance of English folk artist and historian Shirley Collins continues with new album Archangel Hill. She talks Alan Pedder through a lifetime of keeping traditions alive and the songs she holds most close.

Shirley Collins found her purpose early on in life, involving herself in the world of English traditional song as a teenager growing up in Sussex.

Now 87 and continuing a triumphant comeback with her new album Archangel Hill, Collins’ mission remains undimmed. “I want to tell people that folk songs aren’t trivial,” she says. “There are people who dismiss folk music as being light and not necessarily part of a culture. But these songs are part of a culture. They’re part of English culture, and they need to be audible to people.”

It's early May when we speak on the phone and a great swathe of rainclouds hangs over the South Downs. Calling from her cottage in Lewes, less than 30 miles from where she grew up in a working-class family with her older sister Dolly, she’s joined by her musical director Ian Kearey for an in-depth look back at some of her favourite recordings from a career spanning almost 70 years. “My list is almost complete!” she says, laughing. “There are certain songs that I would have wanted to choose as well, but I could only pick five.”

Collins recorded her first two albums Sweet England and False True Lovers, at the same time, over a two-day period in 1958 with pioneering American ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax (her then-lover) and British folklorist Peter Kennedy. The following year, she and Lomax embarked on a journey through the Southern states of the US, collecting folk songs and making field recordings that became a foundational part of the fabric of contemporary music as we know it. That journey is deliciously, sometimes shockingly recounted in Collins’ first memoir America Over the Water and was also the subject of a 2017 documentary The Ballad of Shirley Collins. But it’s what came next that Collins really wants to talk about today.

The five songs she’s chosen were released between 1964 and 1978, but, in the grand folk tradition, have resonated down the years. Her new album Archangel Hill, released next week on Domino Records, features a new arrangement of 'Hares on the Mountain', an English folk song she first recorded in her twenties, alongside a dozen other tracks impeccably chosen and performed.

It’s her third album for the label since 2016, made all the more remarkable by the fact that for almost 40 years before that she had barely sung a note in public. In fact, for much of that time she couldn’t sing at all. After the sudden collapse of her second marriage to Ashley Hutchings (Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span) in 1978, Collins was shocked into a condition called dysphonia that gradually reduced her voice to almost nothing. By 1980, her range had dropped by a whole octave and she retired from performing soon after. But her own work as a folklorist continued, and in the decades since she has been instrumental in keeping the stories of traditional English folk music alive.

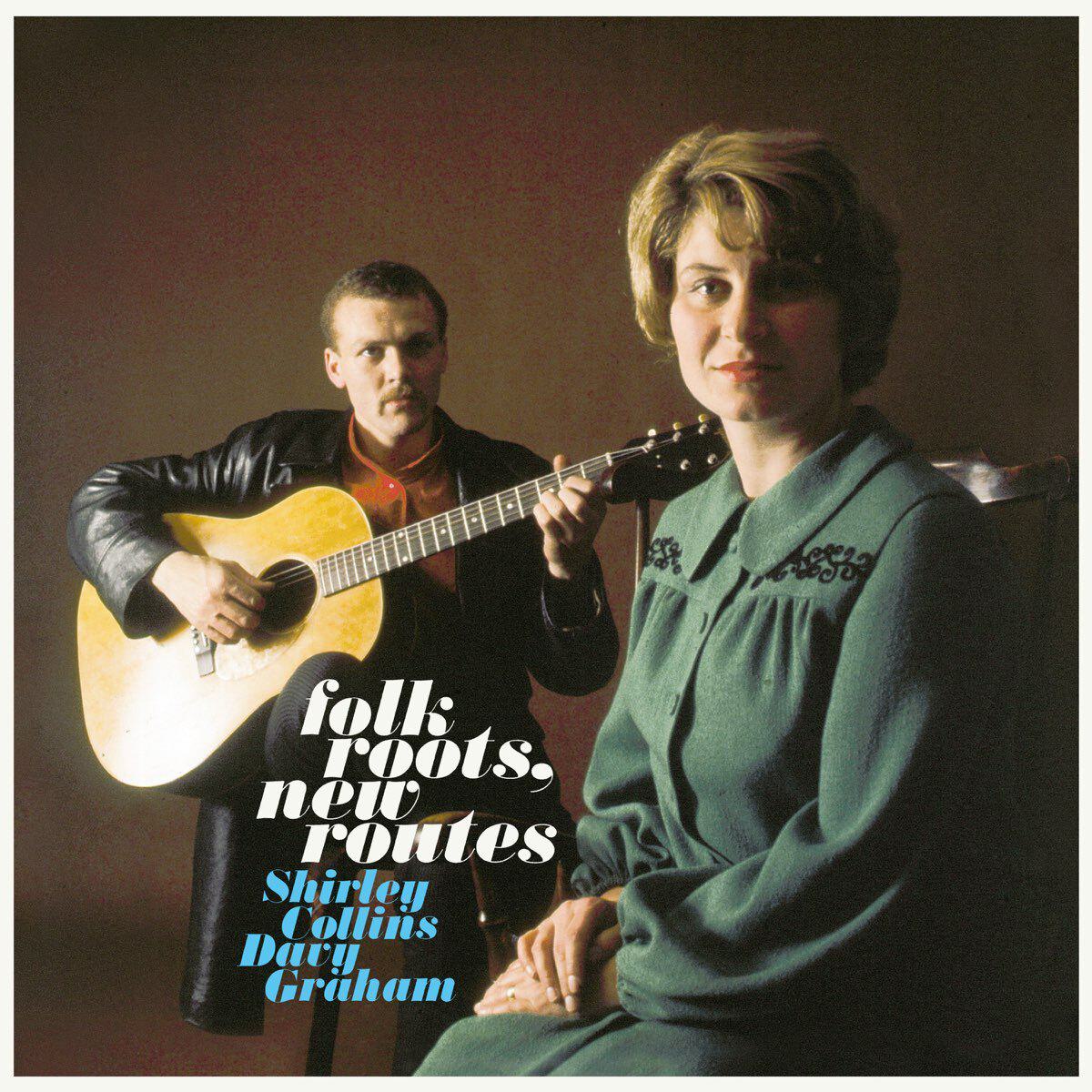

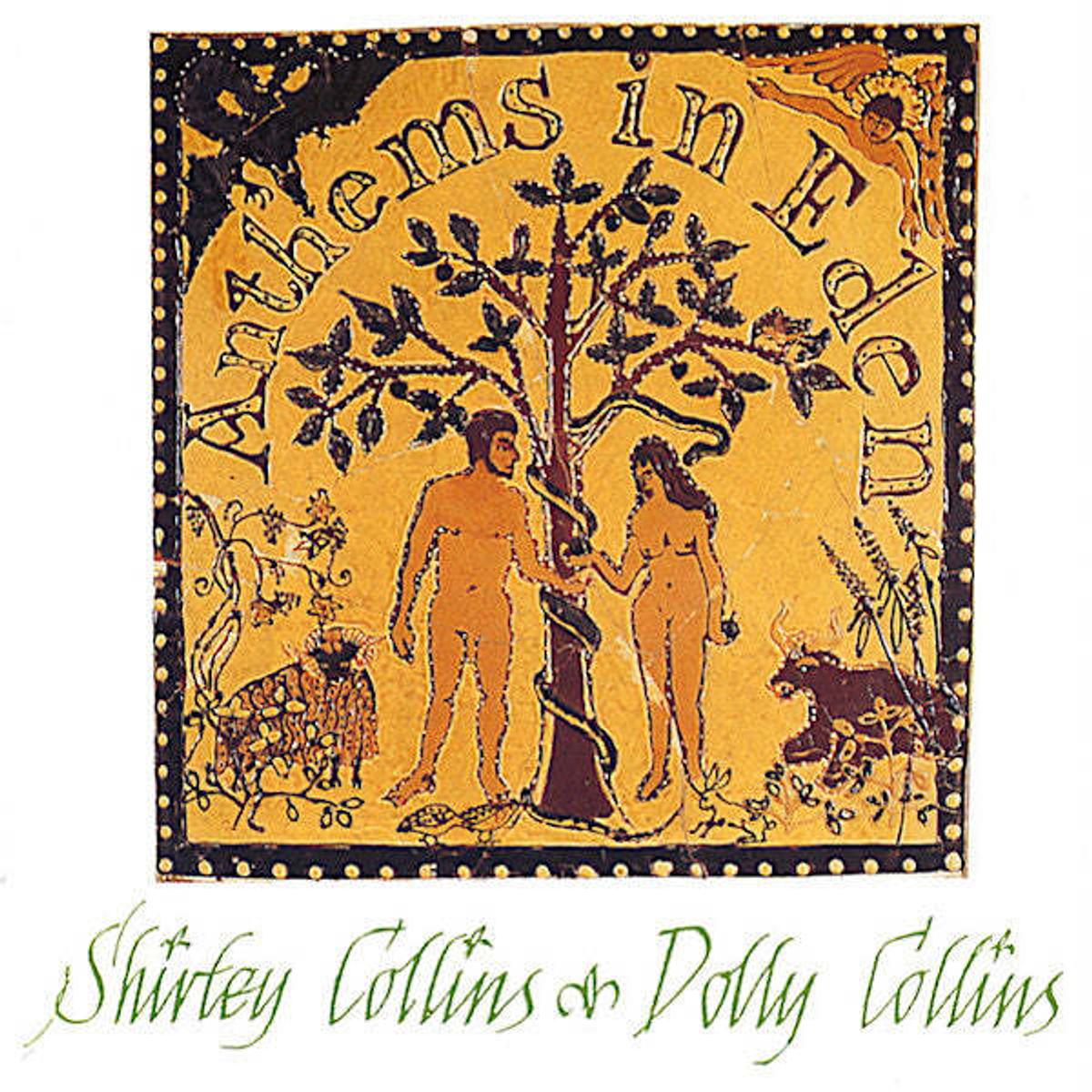

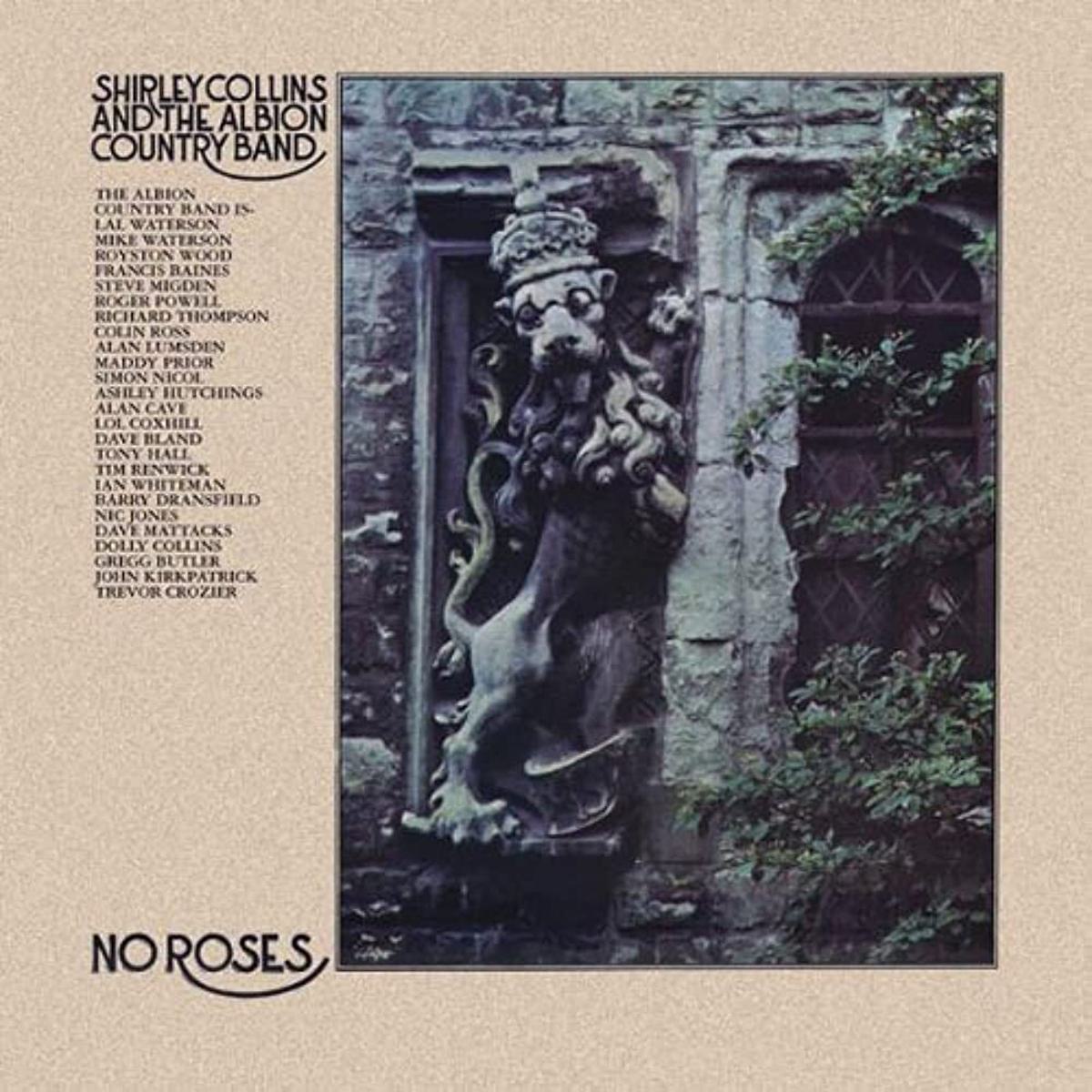

Collins may have felt forgotten, particularly in the lean years when she was forced to sell all her instruments just to get by, but her influence endured. Albums like Folk Roots, New Routes with Davy Graham, Anthems in Eden with her sister Dolly, and No Roses with the Albion Country Band are widely considered as landmark recordings, essential for understanding the British folk revival and its impact on folk music of the 21st century. Collins fans include Will Oldham, Angel Olsen, Meg Baird, Josephine Foster, and Blur’s Graham Coxon, who all contributed to Shirley Inspired, a 34-track tribute album released on the occasion of Collins' 80th birthday in 2015.

Rightly heralded by Billy Bragg as "without doubt one of England's greatest cultural treasures" and by her friend Linda Thompson as "deserving of every accolade that's thrown at her," Collins doesn't plan on stopping any time soon. This coming Sunday she'll make her first live appearance of the year at Brighton Festival with her Lodestar Band as part of the Different Folks weekend curated by Guest Festival Director Nabihah Iqbal.

"Dearest Dear" by Shirley Collins and Davy Graham (1964)

SHIRLEY COLLINS: I chose this first song from Folk Roots, New Routes partly because it’s just such a beautiful song and partly because it also means a great deal to me because it’s the song I quoted in my book America Over the Water.

Alan Lomax and I had been travelling in the Southern states together in 1959 making field recordings, but at the end of that journey he sent me home and that was the end of our relationship. When I put together a show about the whole experience and did a few performances of it in England, we always finished with “Dearest Dear” as a sort of parting.

Some songs never really lose their hold over you, especially the songs that I sing for a reason – because I love them or because they have associations and memories of who I learned them from or who I saw sing them.

BEST FIT: How did you and Davy come to make the Folk Routes, New Roots album together? What values and ideas did you share at the time?

It was the idea of my then-husband Austin John Marshall, who was a great jazz fan and would often go to jazz clubs. Personally, I hate jazz. I just can’t stand it. So when John suggested that I play with this young guitarist Davy Graham, who he’d seen at a club, my first thought was a no-no, and yet it happened. Davy came to our house in Blackheath one day and started to play a version of the Irish song “She Moves Through the Fair”, and it was so extraordinary. I thought it was brilliant, unusual and fascinating, because it hadn’t lost its Irishness but he had added all these North African sounds to it as well. I was really struck by it and agreed to do the album.

It was incredible working with Davy, because his guitar playing was so wonderful. A lot of people criticised that album, the miserable people who couldn’t entertain anything that was slightly different from what they were used to. I mean, there was nothing to complain about with this music of Davy’s, nothing that couldn’t enhance the song. And he played with such energy, such strength and feeling, it was a privilege to work with him.

"A Denying / The Blacksmith" by Shirley and Dolly Collins with David Munrow (1969)

BEST FIT: As far as I understand, it was also John who first suggested that you should make a record with your sister Dolly.

SHIRLEY COLLINS: Yes. I knew I couldn’t make another album with Davy. I think we both knew that Folk Roots, New Routes would stand on its own, and I didn’t really know where I was going to move on to from there.

My sister had studied composition under Alan Bush at the Workers’ Music Association in London. Once a fortnight she’d travel up from Hastings where we lived and have composition lessons with Alan. When Dolly was in London, we were fortunate enough to go together to the Early Music Centre and listen to the musicians there. David Munrow was one of those and we got to know each other a bit, and I think John was the one who sort of made the whole thing happen and brought it all together.

At the time we made Anthems in Eden, Dolly was married to a Morris dancer who was also a schoolteacher. One of the other Morris members was a sculptor and he made the two ceramic figures that appear on the album cover, of Dolly and her husband as Adam and Eve.

To me, the music is sumptuous. There’s not one false note, even though the sound is so big and grand. I remember I just handed all the music over to Dolly and whatever she came up with was just beautiful to sing with. She enhanced the songs in such an unusual way and it was just the perfect fit.

I read she was living on a double decker bus at the time.

She did at one point, yes. Upstairs there was a bedroom, a little bathroom and a kitchen, and there was a sitting room downstairs with a piano. It was parked in an orchard at the back of Oakwood Hotel just outside Hastings, where Dolly and I would go along to sing at social gatherings of mostly Labour Party and Communist Party people coming down from London for meetings. Part of their entertainment was Dolly and me singing. This was when I was about 15 and Dolly 16 or so. We wanted to accompany ourselves and Dolly brought a guitar along, but she didn’t know how to play it so she just open tuned it and laid it across her knees and sort of strummed it, and somehow it worked and we had three bookings there.

Of course, Dolly wasn’t a strummer, she was a composer and she began setting songs to piano. Soon afterwards we discovered the flute organ, a 17th century Romanian instrument, and both fell in love with it so completely because of its beautiful, breathy sound. And that was it for the next few years, really. Dolly would arrange the songs and I remember she would play a few notes and I’d know exactly where to come in. It was magical, all of it. And it still sounds so lovely today.

Anthems in Eden was totally unique in English folk music at the time. People hadn’t really heard anything like it at the time.

It strikes me as extraordinary that it took so long for English folk music to earn that sense of worth and proper recognition of its beauty and its strength. Before that I guess it was a lot of things like Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears singing a ribald version of “The Foggy Foggy Dew”, where the line ‘Now I’m a bachelor I live with my son’ would come up and the audience would have to laugh because it was a bit sexy. Ugh. I couldn’t bear listening to it.

There was some controversy surrounding Anthems in Eden, but most of it came from the Ewan MacColl lot who wouldn’t brook any other way of singing than, you know, putting your hand behind your ear so that everyone knew you were serious about it.

One champion of the record was John Peel, who premiered the original Anthems in Eden song suite on his radio show. That must have been huge for you.

Oh yes, that was an incredible thing to happen. It was so unlikely, in a way, but he was so open to all sorts of music and fortunately he really liked it. It was extraordinary to have that support, which obviously helped me reach a larger audience than I had reached before. And as a suite of songs, I think it all fitted in so beautifully.

I chose “A Blacksmith Courted Me” because it reminds me of Dolly and how much we achieved in terms of putting folk music in front of people as a work of art but without it being ‘arty’, if you see what I mean.

You’ve recorded a few versions of it over the years. I think it’s fair to say that this song has definitely travelled with you.

It certainly has. It’s one of my absolute favourite songs. It’s a song of love but it’s a song of loss, too. It’s the sort of song that once it gets hold of you it doesn’t let you go.

I first heard this song sung by an English Gypsy called Phoebe Smith, who sang in the most fantastic way. She was one of the finest of the Gypsy singers in England. It was a song that was really widely sung, and I’ve heard so many versions and field recordings of it throughout my life.

You know, the Gypsies were great carriers of song since they were always moving around the country. They would pick up songs that local people would sing, perhaps around the campfire, and they’d not only learn those but they’d leave some others behind as well. There was this great mixture of songs going through the whole Gypsy community and local settled communities in the 19th and 20th centuries. Sadly that’s died out now, so it’s great that so many have been recorded by people like Peter Kennedy.

One of his other great sources of songs was Caroline Hughes, who had a huge repertoire of traditional ballads. At one point during the recording, her husband John said that he’d like to sing a song [“The Little Chimney Sweep”], and of course Peter asked him what the song was about. He said it was a song about a child that had been stolen from its mother, and then a few years later she hired a chimney sweep and noticed a birthmark on his arm and recognised him as her own child.

It’s an incredibly rare song. I’d never heard it before. And Peter asked him ‘Where did you learn this?’ and John Hughes said, ‘Well, I heard it from a shepherd at a fair in Winstanton.’ Peter said, ‘Yes, but how did you learn it?’ to which the answer was simply ‘I heard what he sung.’ It’s amazing how so many singers can learn a song just by hearing it once. They have the ear for it and songs just soak in, and I think that’s fascinating.

"Poor Murdered Woman" by Shirley Collins and the Albion Country Band (1971)

BEST FIT: No Roses is a landmark album in British folk-rock. Is it true that the Albion Country Band was formed especially for the record?

SHIRLEY COLLINS: Well, yes it was. I mean, I’m not sure you can call it a band that was formed because it all happened sort of fortuitously, in a way. When we’d got the songs planned and we’d put some basic recordings down with Richard Thompson and Simon Nicol, we went to Sound Techniques Studio in Chelsea to record it and Ashley invited all sorts of people in as well. People like Lol Coxhill from the jazz world and several folk musicians.

The small studio would get more and more filled up with people and more instruments would come out. There was a hurdy-gurdy and more unusual things. Everything worked together and the music just happened really. Most of it wasn’t written, though. Only the arrangement for “Poor Murdered Woman” had been written in advance.

There are several songs on that album that I think are wonderfully, beautifully played. I chose “Poor Murdered Woman” because it’s a story that affected me from the start, a true story that was reported in the local paper about a woman whose body was discovered by a foxhunter on the common in Leatherhead. The song was written by a local man in a way that was not typical for a poem or song in the way that the words were put together. But they’re put together in such a way that it tells the whole story and makes comments about it at the same time. It’s majestic storytelling, it’s fabulous.

The woman was buried in the churchyard at Leatherhead. We know she’s there but we don’t know her name or anything about her. She’s just the poor murdered woman. I think it’s interesting that the huntsmen who find her just rode away and left the body there until the next day when they came back with a coroner. The whole story is there, and you have this magnificent arrangement with rows and rows of people in the studio. At one point Ashley got out this big bell and hit it, but he didn’t do it in rhythm with the song and it worked so well. It felt very real, as if it was a real bell being tolled.

I was going to ask you about that! It gives me chills every time that bell sound comes in.

It’s amazing, isn’t it? It’s just so cleverly done. I think anybody else would have just hit the bell in time to the song, but he veered away from that and I think it really adds something to this really old story.

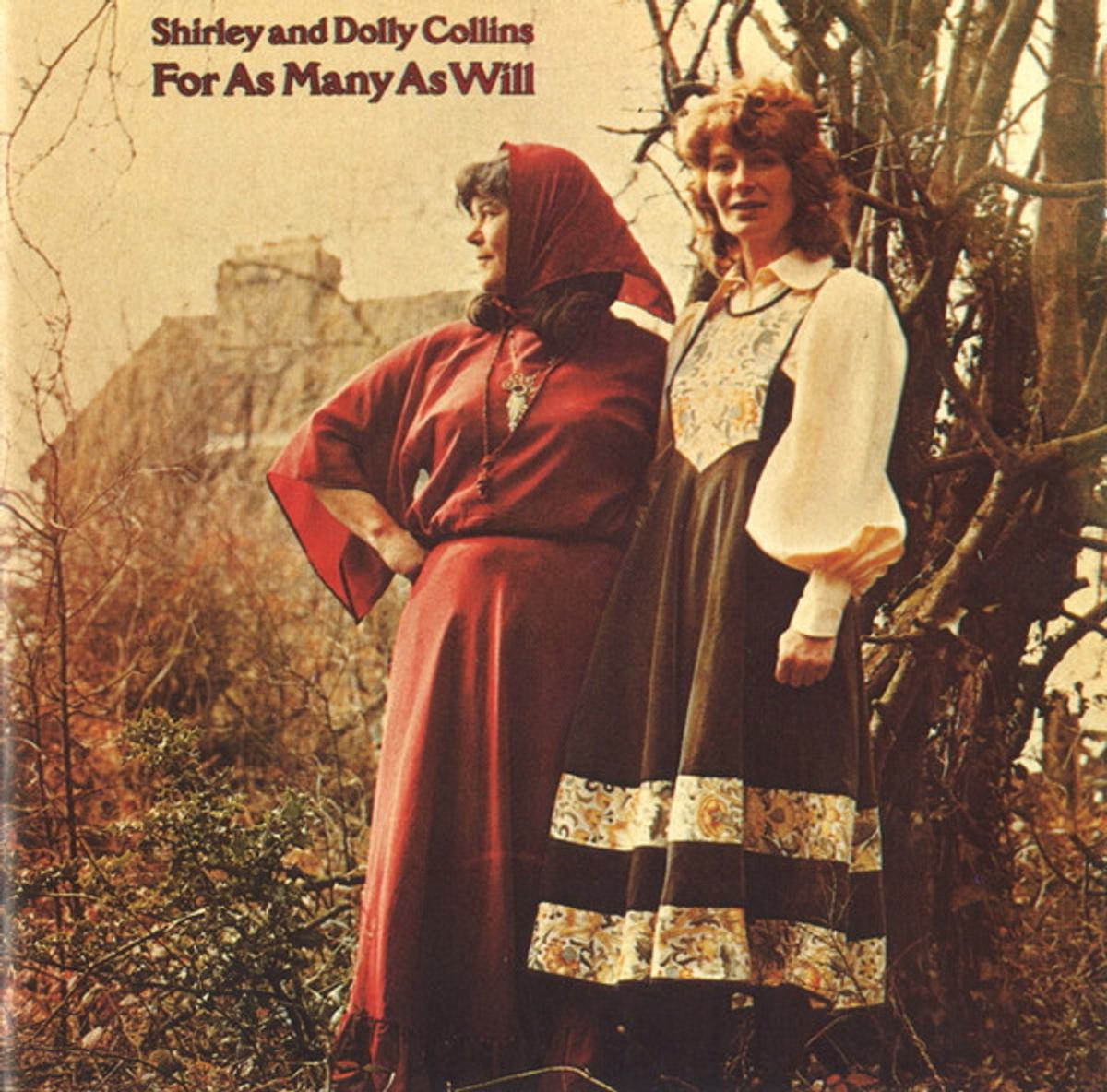

"Gilderoy" by Shirley and Dolly Collins (1978)

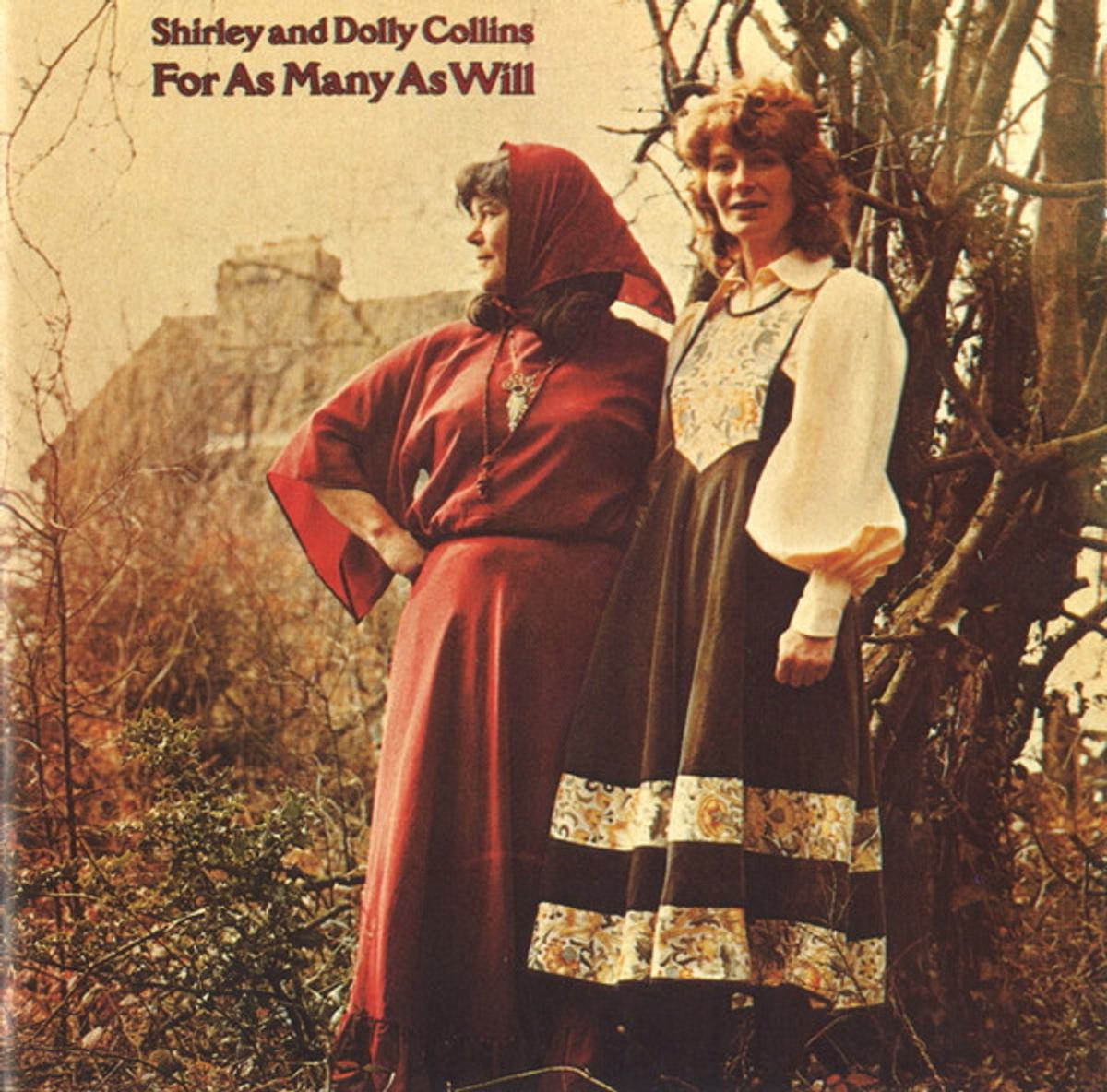

BEST FIT: The last two songs you’ve chosen are both from For As Many As Will, which was the last album that you and Dolly made together. What does “Gilderoy” mean to you?

SHIRLEY COLLINS: I’m always fascinated by how songs travel and this one travelled a great distance from Scotland before it made its way to Sussex over the centuries. It was notated from a man who lived not many miles from here, in Horsham, though of course it had changed along the way.

It’s a song about a man who was a marauder, who wasn’t a good person, and the whole story is sort of condensed into this domestic situation. It’s a love story from the perspective of a woman singing for this lover of hers who ends up being hanged. I think it’s one of Dolly’s finest arrangements, it’s so noble. In many ways it shouldn’t be a noble song because it’s about a thief, basically, but it’s just magnificent. It’s wonderful how it rises higher and higher at the end. It feels so wonderful to sing. I’ve listened to it over and over and over and I never get tired of it. It’s a song I wouldn’t have missed singing for anything.

Looking back, I do sometimes think the grammar is wrong in the album title. Perhaps one should say ‘for as many who will’ or ‘for as many that will,’ but it originally came from the title of an English country dance by John Playford which described it as a dance for as many as will, and we just kept that.

"Lord Allenwater" by Shirley and Dolly Collins (1978)

SHIRLEY COLLINS: This is another song that travelled. There was a Lord from the Scottish Borders, the Earl of Derwentwater, and there are several songs about him. This one is a true story about how he was a part of the Jacobite uprising in the early 18th century and therefore a traitor to the King, but he denied it. The story in this song is that he was arrested in London and beheaded, and the axeman says ‘Now there lies the head of a traitor’ but the head answers ‘No’. He denies it again, even after death.

This song, again, made its way to Sussex. In fact, as we eventually found out, it was sung by a great grandmother of Ian Anderson who founded and ran the magazine Folk Roots, or fRoots, until fairly recently. He was so thrilled to find out that he had a great grandmother who sang one of the rarest folk songs in Sussex. I think there was just one version in Sussex and the rest were from much further north.

I love the storytelling. At the start of the song, Lord Allenwater gets a letter from the King that he has to attend to him in London, and he knows almost from the start that he’s not going to be coming back. Then all sorts of things occur to him on his journey south, like his horse stumbling on a stone – signs that make him aware that he’s heading towards his death.

Again, the tune is such a noble tune and fabulous to sing. There’s also that interesting grammar right from the start, ‘The King has wrote a long letter.’ The minute I see things like that in a song, it makes me want to sing it.

BEST FIT: It’s interesting that you’ve chosen these two traditional favourites from For As Many As Will, because actually that album had a few modern touches. For instance, Dolly plays a synthesiser on several songs, and you also did a cover of a song by Richard Thompson, which you’d never done before.

Yes, we recorded his song “Never Again” because it expressed a bit of what I was feeling at the time. Ashley, my then-husband, had kind of wandered off into the land of the theatre and had fallen in love with at least two actors and had left me. So the song felt very personal and I connected with it so strongly. Richard always did write such incredible songs. This one is very tender, I think, and Dolly’s piano was so beautiful to sing with.

So much happened after this album, with you losing your voice and Dolly giving up the recording and performing side of the music, preferring to compose instead.

Although Dolly always really enjoyed writing the arrangements to the songs we’d chosen, she always used to say to me, ‘I’m a composer, I want to write my own work,’ and eventually that’s what she did. She was always more of a homebody than I was. She had this beautiful garden and a young child that she couldn’t bear being away from, and I was losing my voice anyway. So it just happened that we never made another album together. We didn’t depart from each other as sisters, only as singer and arranger, and then there was a long, long period of silence.

I think it’s a really lovely touch that you’ve included a live version of "Hand and Heart" on your new album, which has the original arrangement by Dolly and also lyrics by your Great Uncle Fred.

I have loved this song for so long and I’m really happy that it’s on this album. It was recorded in Australia in 1980. I’d asked Dolly if she’d come with me but she didn’t want to leave her child, so I went alone. I took her arrangements with me hoping that they could be played at the Sydney Opera House concert, where I had a wonderful harpsichord player, Winsome Evans, join me.

For the rest of the bookings I had to sing unaccompanied. I didn't have my five-string banjo or any other instrument to take with me. I'd had to sell them all because I was so hard up at the time. But by good fortune, Ian Kearey bought 'the Instrument' [a unique five-string banjo/dulcimer hybrid] that John Bailey had made for me in 1961, and he still plays it. It's there on all three Domino albums.

As you say, the words to "Hand and Heart" are written by my Great Uncle Fred, a lovely, lovely man. He was a gas meter reader by day and wrote books under the name of F.C. Ball by night. He was also the biographer of the great working-class writer Richard Tressell and was the one who found the complete original manuscript for The Ragged-Trouser Philanthropists.

Uncle Fred wrote mostly novels, which were set in Sussex, and it was he who played things like Monteverdi and Purcell to me and Dolly on the gramophone at his house. In that way, he introduced us to a wider range of music than we would normally have, because at home we only had the radio, or the wireless as we called it then, and there wasn’t much on there that we wanted to hear.

He wrote the lyrics to this song as a very young man, He was engaged to one young woman but had fallen in love with an art student. In those days, if you broke off an engagement it was called a 'breach of promise' and you had to pay compensation to the woman you were not going to marry. His family had no money at all, so he had to let his sweetheart go and marry the woman he was engaged to who he didn’t love anymore.

It’s on the album as a little nod to what I used to be. Since this live recording my voice has dropped a whole octave, but I think it fits in well with the new songs on the album. I’ve also got my dad on the album, on the final piece “Archangel Hill”. It’s a poem that he wrote during the Second World War when he was away with the Royal Artillery, and I think it’s beautiful the way that Ian has brought it to life with the music he has written for it.

It's a real family affair.

Yes, sort of! Ian is family as well, really. I’ve known him for so long. He and Uncle Fred used to get on so well, having known each other right back in the ‘60s, so I’m really glad to have them both on the album, as well as my dad.

Archangel Hill is released 26 May via Domino Records. Tickets for the Different Folks weekend are available through the Brighton Festival website.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex