New Life

Sophie Walker meets Paramore and finds a band healed from the scars of their own history, embracing the simple joys of making music together again.

The sky is blue, the grass is green - and there is Paramore. Shades of the band have bled so completely into today’s pop landscape that their significance is hardly a matter of opinion, at this point, but empirical fact. Listen to music that defines the zeitgeist and it’s like the band have walked through a hall of mirrors: there may be distortion, warping their foundations to newfound extremes, but beneath it all, they are the real image.

There is Paramore in Olivia Rodrigo’s white knuckles, hot tears and sharp tongue; the parallels between “Good 4 U” and the band’s seminal pop-punk anthem “Misery Business” were so undeniable that Rodrigo retroactively granted singer Hayley Williams a writing credit. There is Paramore in Billie Eilish’s tenderness that blooms like a deep purple bruise, a young woman daring to express emotions usually denied to her. There is Paramore, even, in the electric and raw-nerved confessions of Lil Uzi Vert who declared Williams to be “the best… of my generation”. They’re there in pop’s bitter truths with sugar on the rim; right there, in every anthem for a doomed youth full of hope and fight.

While the world’s love affair with Paramore has only intensified over the years, proving time and time again that they’re not merely a nostalgia band for the emo epoch but a constantly growing, evolving unit of artists whose work defies generational borders, their love story with each other isn’t quite so easy to tell. Making sense of Paramore requires a tangle of red thread and a colour-coded timeline for the band’s ever-changing line-up – that, and a suspension of disbelief. Over their six hard-won records, theirs is a story of teenage dreams and unbelievable heights, lawsuits and long silences, the kind of betrayal that makes its incision right between your shoulder blades and the strength of chosen family. And somehow, they’re still here. And no one is as surprised about that as Paramore.

You could say this story starts in Franklin, Tennessee, 2002, when a 13-year-old Hayley Williams met brothers Josh and Zac Farro at a program for home-schooled students. But really, it starts long before that: as a child, Williams would doodle in the pages of her journal. It would be herself and her then-unknown friends playing instruments. The band. Growing into a five-strong group of neighbourhood kids bonded by a shared passion for alternative rock, after school they couldn’t head to practice together fast enough.

But when their sound was brought to light - staggeringly sharp for their age - a bidding war ensued not for Paramore, but for Williams alone. She was the ninth grader powerhouse vocalist that labels were determined to cram into an Ashlee Simpson-shaped cookie cutter. While many refused to entertain the idea of an alt-rock band even optically, Atlantic was the only label that would allow her to bring the guys with her. Paramore would be something she would grow out of, they were certain; the band was a streak of sweet teenage rebellion like a bad haircut. In time, they were sure she would bend.

Lulled under the false security that she would be bringing the band with her, the fifteen-year-old girl was the only member to sign along the dotted line. From then on, it implied that it was ‘Hayley’ and ‘The Band’ of lesser worth, and the damage wreaked by that decision is something Williams has spent her career relentlessly trying to reverse.

During the reign of pop-punk and commercial domination of emo, Paramore stood as a flagrant exception to a scene which had double-bolted the doors against women. While teenage girls, as ever, were the lifeblood for these bands, on the stage itself, they were almost entirely absent. Critic Jessica Hopper wrote for Rookie: “On a pedestal, on our backs. Muses at best. Cum rags or invisible at worst… Emo’s yearning doesn’t connect it with women – it omits them.”

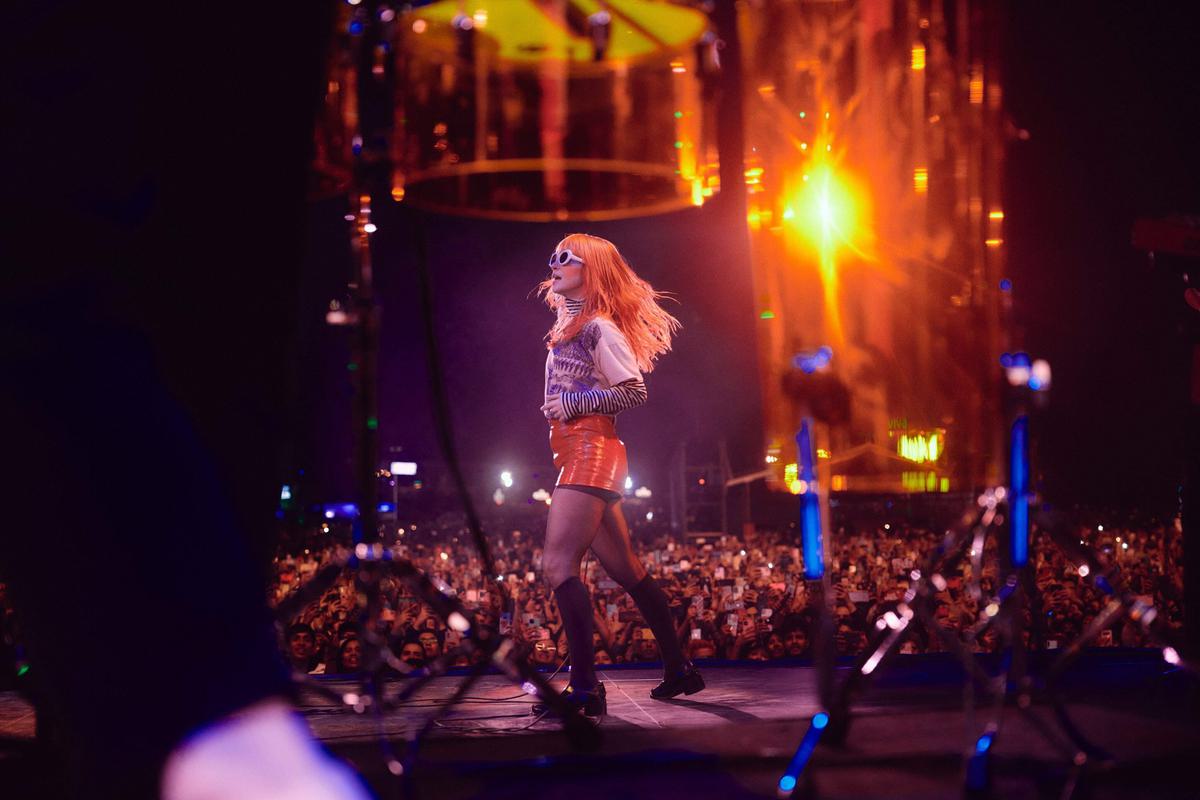

Williams threw on the lights for those young girls, blazing proof that their participation was possible, that with sharp elbows, they could fight for a seat at the table. Paramore’s was a collective voice that refused to be drowned out, a rallying cry for the alienated that has forged unshakeable bonds with communities that refused to conform to emo’s white, straight and dominantly male status quo.

Their defining 2007 album Riot! Was certified double-platinum with chart-scaling success, but there is really no misery business quite like growing up under the glare of the public eye. Like Wendy and The Lost Boys, Paramore were spirited away to Neverland: their growth as young people was stunted and scrutinised, their mistakes magnified. Williams dated band member Josh Farro, penning “Misery Business” in a flush of teenage rage. As a grown woman who no longer supported the song’s lyrics, removing the track from their setlist, this was only one of many ways she was unsympathetically held to her younger self’s mistakes. “People still have my diary”, she wrote on her Tumblr page.

During her breakup with Josh Farro, who made a highly publicised exit from Paramore along with his brother Zac in 2010 following Brand new Eyes, he detailed how the project was always intended to unfairly showcase Williams and the band was simply “riding on the coattails for ‘Hayley’s dream.’” This interpretation was undoubtedly worsened by misogynistic portrayals of Williams in the press, including, most notably, a Kerrang cover story in 2007 which described her passive bandmates as “[paddling] along like ducks in her wake”; she was a domineering puppet master vying to be centre of attention. In 2015, bassist and founding member Jeremy Davis followed suit, departing after the release of Self-Titled and later unexpectedly suing Paramore over authorship and royalties.

Despite having to navigate and heal from trauma both personal and professional, the remaining members have never given up on Paramore. Returning with their sixth record, aptly titled This is Why, this is the first to be made by the same line-up as the previous one. Hayley Williams, drummer Zac Farro who reconciled with the band for 2017’s After Laughter, and guitarist Taylor York, are now in their early thirties, possessing a kind of serenity granted to those with hard-won experience. They’re gathered in front of a fireplace on a bright Nashville morning, a composition fit for a family Christmas card. For the album, the band refuse to be photographed separately; there is no voice here that carries more weight than another. This is not just Hayley’s band.

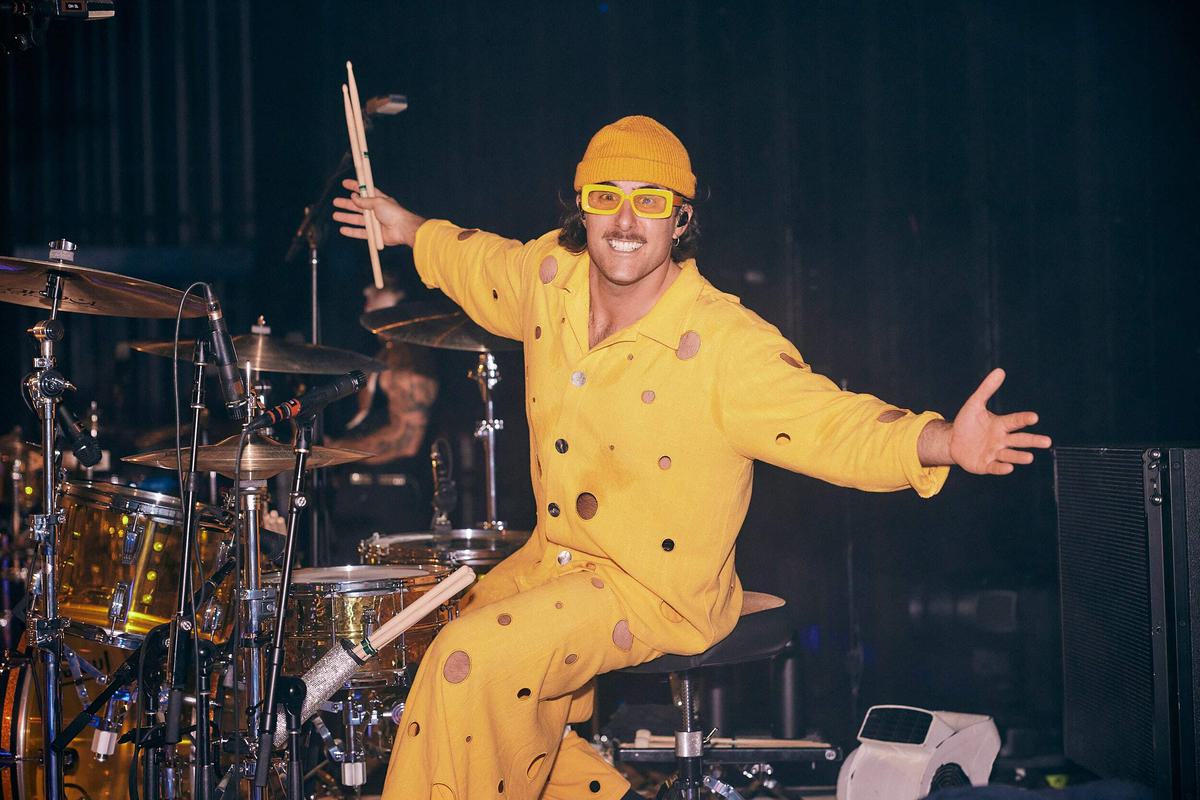

It’s a great time to be Paramore, and this time, they really mean it – not a paper-thin sentiment said through gritted-teeth and false smiles. There is a therapised patience between them, a genuinely held sense of admiration and affection. Laughter comes easily, and they listen to each other with rapt attention; careful to speak as individuals, careful to be fair. “There’s not a big shitstorm going around, if that’s a thing,” remarks Farro, always the first to temper a moment of introspection with his endearingly awkward sense of humour. “I don’t even know what a shitstorm is, but…” William fills the pause with a smirk: “It’s the definition of our band!”

After finishing the After Laughter tour, the question of returning to Paramore was open ended. They took the intervening years to figure out their own identities without being handcuffed to the band. Williams admits: “It was scary. You know that you need something, but taking a step toward that is easier said than done, right? We all knew it was time to go home. Also, it was the reality check of being a daughter, being a sibling – all these normal, everyday dynamics that we get the benefit of running away from when we’re on tour. I feel like that was more influential on this album that we’ll ever know... We’ll never actually understand what that did for us. As creatives, you need to recharge and you need to experience real situations - not situations that are curated for you, where all the snacks that you want are there, and all your clothes are hung out for you. That’s not reality.”

York offers, “Zac was really great about helping us not resist where we naturally wanted to go. Having that time off, I think we were all able to detach from feeling like a business entity.” Williams made two solo albums to reckon with wounds still unhealed, addressing the toll that the band and her divorce from Chad Gilbert of New Found Glory had taken on her. Farro pursued his own solo project, HalfNoise, and York took the time to detox from relentless touring, quit drinking and pursue his passions without pressure. They also decided not to confine this time away to a deadline. “We weren’t gonna be like, ‘Alright, we’re gonna take a whole year off and then, at the stroke of midnight, we’ll be back’”, says Williams. “We never called it a hiatus, or anything that was like, ‘Will they? Won’t they?’. We always knew we would come back.”

While the band was practising wilful withdrawal, the turn of the pandemic really forced their hand on the matter. “It was horrible, horrifying – and really humbling,” Williams remarks. “Every single person is running around like a chicken with their head cut off trying to get their mission fulfilled, right? When the pandemic really struck down on everyone, it brought everything to a full stop. We were all at home in our community, our family dynamics, and there was no way around it - you gotta go through it.” This creatively fertile period proved to stoke the flames for This is Why largely because they had the opportunity to finally sit with music, stockpile inspiration and approach to everything, first and foremost, as a fan.

"We don’t see our past as more valuable than where we have left to go."

When they made the first tentative steps toward making This is Why, it felt like a natural gravitation without the pressure of a label breathing down their neck.

“We didn’t strategise it, and I think if we’d tried to, we probably would’ve imploded in one way or another,” says Williams. “We didn’t do it for our career,” York insists, despite recognising that Paramore seems to have grown exponentially even while their backs were turned on it. The pandemic welcomed an appraisal of Paramore’s legacy as people were tumbling down rabbit holes of emo nostalgia, with Gen Z having excavated the scene and, through a rose-tinted lens, restored it to grace. A flood of think pieces on the band’s legacy were published in their absence. Pitchfork explored the scale of their influence on today’s artists, and many articles were dedicated to the unique relationship between Paramore and their Black fans, including a personal, self-published piece written by Clarissa Brooks. To top it all off, last summer the band headlined the hotly discussed When We Were Young festival alongside My Chemical Romance, which capitalised completely on ‘elder emo’ reminiscing.

But Paramore are not a nostalgia band, Williams emphasises: “We don’t see our past as more valuable than where we have left to go.” But there was, she admits, a sense of pressure about returning when the band had been so highly elevated, almost a necessity to retrace old scars. And that starts with looking in the mirror. “I’m having an identity crisis around red hair again,” she tells me. “It’s like as if I don’t know this person anymore, and I’m trying to get to know her again.” Bleaching her hair to a blank white slate in the After Laughter era was a crucial in freeing her from the implications of being ‘Hayley from Paramore’. “People have a very specific idea and expectation of who that person was. I carry parts of her with me, for sure, but I’ve grown and changed – as you do – so much since Paramore became a thing. I’m trying to learn to reintegrate those parts of me with who I know myself to be personally.”

There’s also the question of what expectations are leveraged onto the band, too, having won over a fresh generation of listeners. Williams continues, “There’s all these new fans who are nostalgic about something they didn’t experience. It made us question, you know, ‘What are we? Are we going to try and offer something? Are we going to try and rehash this old thing?’ While we were writing, we kept calling it an old jacket. Like, ‘Are we going to put the old jacket back on and try to do the thing?’ And it just never felt right to do that. It’s not the first time we’ve experienced that because every time you have an album with any degree of success, I think there’s this external pressure that says, ‘If it’s not broke, don’t fix it’, kind of thing. That has never sat well with us. We’ve always wanted to just break some new shit.”

It’s the strength of their friendship, however, which overrides every anxiety. “We worked out most of our bullshit a long time before making this album,” says Williams. “The only conditions these days are that our relationships with each other come first, and mental wellbeing comes before career.” York is a self-confessed introvert who measures his thoughts carefully, and so they are often eloquently put: “Every time you start a record, it feels like you’re staring up at a mountain. You don’t even know if that mountain is a mirage, or if it’s even scalable. But we believed in it.” This is Why is an effort of three. “This is the most collaborative record we’ve made top-to-bottom,” York believes. “We were all involved in every part of the process, and we’ve never done that before.”

On the Paramore subreddit, a post asserted that something every new Paramore fan should be aware of is that “we owe Taylor York everything”. Besides Williams, he is the band’s most enduring member – “the literal glue that holds Paramore together”. It was York who reached out to Farro after his departure ask if he would be their studio drummer for After Laughter, which led to a rekindling of their friendship and eventually resulted in Farro returning to the band permanently. After Williams quietly left Paramore for a brief period due to her struggles with depression, she praised York, her closest songwriting partner, as being one of the reasons she is still alive. He produced Williams’ first solo album, Petals for Armor in 2020, a return to softness and a release of rage, and helped her to adapt a love song which her grandfather wrote for her grandmother, a closing track which they titled “Crystal Clear”. In a recent interview in The Guardian, they confirmed that they were dating.

New life. That’s how York describes This is Why. Williams calls it “free therapy”, passing around a guitar, trying things out, shedding self-consciousness and learning how to collaborative from the ground up. “It was fully an exercise for Paramore,” she elaborates. “But I feel like what it does for you as a person, that kind of vulnerability, is kind of humbling. So many times we would get in a room to write, but this time, we just ended up talking and hanging out, sitting on the porch together.” Simplicity is a word that keeps returning when they tell me how the record defines an era of their lives, and they wear it well.

The conversations they were having were sometimes easy, and other times, unavoidably heavy. Lyrically, This is Why sees Paramore turn their gaze from within and out into a world fraying at the edges. They want to look at that edge - where Black lives must fight to matter, where women are denied the right to have control over their own bodies - and talk about it. While being grounded in their hometown of Nashville, a famously red state whose politics is informed by religious reasoning, society’s fractures had never felt so glaringly obvious.

Sonically, the band entangle themselves further in their love affair with new wave and its tailored paranoia; its stylish theatrics which distract from its unsettling undercurrents. While there is something of Bloc Party’s angular guitars in “The News” and reverberations of references as specific as The Ting Tings in “This is Why”, peel back the band’s influences a little further and there is the unmistakable prowl of Talking Heads’ “Psycho Killer” and the eerie atmospherics of Siouxsie and the Banshees. The imagery for This is Why, an off-kilter, surreal reimagining of 60s iconography, underlines the band’s interest in a sound and style that makes subtle gestures to the anxiety of the world around us. Yes, they still shrug on the old emo jacket for select moments on the record, but they’re not beholden to it.

With tracks like “The News”, which reckons with the way its agenda has us in a chokehold of guilt and powerlessness, and “Big Man Little Dignity” which takes aim at the chauvinistic behaviour of men in positions of power, Paramore, out of necessity, have become something of a political band. “There was no getting away from it,” reflect York. “But we were certainly not a political band before this record. I think we were really frustrated – frustrated being an understatement - about Trump. Those conversations were happening. But I think this is the first time we were really diving into some things that we were ignorant about, that we needed to learn from and share with each other. Those conversations really opened up the door for us to start a new season as a band - the fact that it’s okay to be political in the sense that we have a voice to say things that not everyone will like.”

At first it was hard to imagine how Paramore corresponded to the caricature of what a political band is. Growing up, there was a particular sound and aesthetic they felt a band had to subscribe to in the vein of Rage Against The Machine and Public Enemy. But as our understanding has evolved and the borders of genre have eroded, there is room for a far more nuanced vision of what a band with a sense of social responsibility can be. “Being at home, we really got to dig in and feel part of our community,” says Williams. “We’re affected by politics in a completely different way because our privilege and position, but we realised that we’re just as much responsible for the state of the future as anybody else. We have an opportunity to take that energy and do something good with it – that’s the power of the band. Someone is listening.” Having spent much of their time away from the band marching, speaking up and working with local organisations, now Paramore is back on the scene, one of their first moves was to donate a portion of tour profits to reproductive care and abortion services after the overturning of Roe V. Wade. “You don’t have to sound like a punk band to be attuned to injustice,” says Williams.

When discussing the qualities they were striving to capture with This is Why, a sense of urgency is something they can all agree on. “You can’t live through what we’re collectively been through without a sense of urgency,” believes Williams. “Like, the planet is dying and we’re all still fighting about a superior race. We’re gonna get eradicated pretty soon, you know what I mean? If you don’t have a sense of urgency, you need to check your pulse. There was this thing in the air, an electricity between us: we were feeling the input of the world and everything that we’d been through together, and I don’t think we could escape it. If we hadn’t been reflecting on the state of the world, then I think we’d be doing ourselves and everyone else a disservice.”

“Would you like us to expand on that?” jokes Farro.

"I think Hayley did a lot of self-reflection on this record, and I think that’s a huge step forward step forward in showing that there’s no shame in admitting things or processing things outwardly."

There is a sense of internal tension, a dichotomy of being both hero and villain, across the songwriting on this album perhaps best defined by lyrics in “You First”: “Turns out I’m living in a horror film / Where I’m both the killer and the final girl”. It’s something Williams admits to having experienced in extremes. “You’re somebody’s hero, and they come up to you and tell you about all these things you’ve helped them with, but in the back of your mind, you’re thinking, ‘But I’m an asshole’ about something you did or a mistake you made. Like, this person has no idea, right? But I think that’s just the paradoxical nature of being human. I got mad at kids for a fighting at a Paramore show and then I got mad at myself backstage because I was like, ‘As if I don’t get angry about shit’, you know? Who knows what they’re struggling with, or if the world is a horrific place to live in for them? Maybe they don’t have money for therapy? Maybe they’re going through something I can’t even fathom, and it’s no wonder they got into a fight at the Paramore show.”

Particularly with the lyrics of “Thick Skull”, the album’s final act, there is a pervasive sense of self-blame. She sings mercilessly of herself: “Thick skull never did / Nothing for me / Same lesson again? / C’mon / Give it to me.” She expands, “The last song of the album is reflective of my biggest insecurities throughout our career. The shit people projected onto me all these years: saying the band is manufactured or that I’m using my friends for my own personal career advances… I decided to speak directly to those fears, even indulging the naysayers. This being the last album of this era of our career as part of the same contract I signed as a teen, I just want to leave all those fears and the bullshit here. I’m not taking it with me any further.”

I ask if, as a band, they have learned through the process of the album to forgive themselves for what their lyrics reflect. “I mean, I think we’ll be doing that forever,” says Williams, before tapering off in thought, “You know, I don’t know…” Farro shares, “I think it’s a process of maybe not forgiving yourself but expressing your vulnerability. I think that’s a huge thing with any issue with your mental wellness, to first examine it and then admit it. I think Hayley did a lot of self-reflection on this record, and I think that’s a huge step forward step forward in showing that there’s no shame in admitting things or processing things outwardly.”

"“It took us half our lives, but we finally know how to be better friends to each other."

And so, being finally released from the contract at Atlantic which Williams signed as a teenager and had held the band in a chokehold for over two decades, this chapter of Paramore is drawing to an end. A line is drawn. Expanding before them is the vast, gleaming promise of a future that is entirely theirs to write.

When I ask what they’ve learned through the process of This is Why, York laughs, “I definitely learned that I need to find a therapist again,” before adding, “and that making art with your friends is the coolest, most unbelievable gift. I love recording more than anything, but you wouldn’t know it from how emotional I get, how insecure I can get. But it’s amazing that I get to do this with people where I’m in their corner and they’re in mine, because sometimes it doesn’t bring out the best parts of yourself. Everyone is working through something different, whether it’s fighting a demon or experiencing the ultimate joy in being able to do what you’re doing. I’m always so grateful that we’re in a place like that as a band, because though I certainly find it difficult to forgive myself, I think it has been cool to show each other forgiveness.” Farro jokes, “That’s not what they’re telling me behind the scenes!”, adding, “I think we’re just not as resilient as we think we are. We need peace, we need quiet and rest so we can come back and rock.” Williams concurs, “We’re soft babies. We will always be a mess and we’ll never have it all figured out. It might even be the blatant denial that keeps us here.”

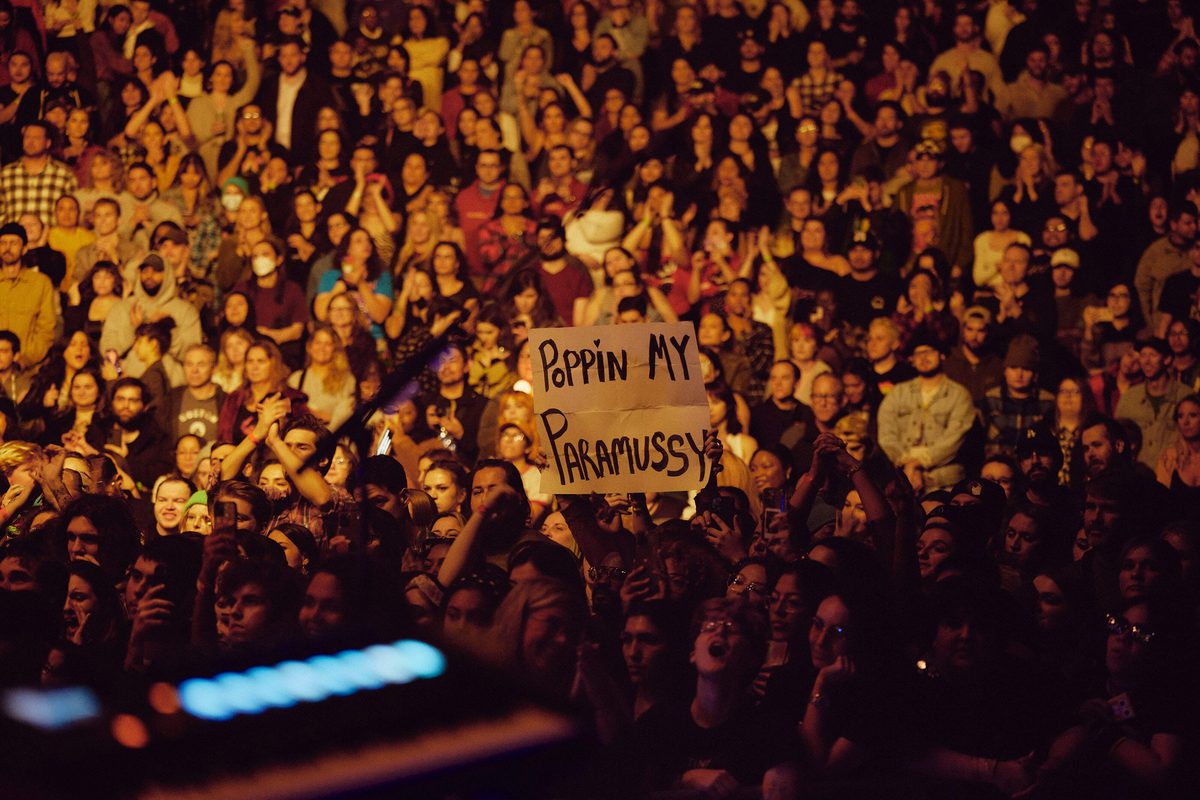

Now, almost two decades since they met, Paramore are questioning what their legacy will be, what will remain regardless of what the band’s future holds. “It took us half our lives, but we finally know how to be better friends to each other. Success may as well have nothing to do with our career. We still love being around each other. Man, the bands that we love are such great connectors,” says Williams. “We really want to offer something that feels welcoming and warm. A safe space. Ah… a ‘safe space’,” she rolls her eyes. “Doesn’t that sound like it’s not even a real phrase anymore? But whether it’s at our shows, how we conduct ourselves or what we choose to highlight, I want people to look back on the diversity of the crowds when we’re on stage and how beautiful that is to us. To me, that is a much better legacy to leave behind than fuckin’ bops, you know? We want to make great art, but more than anything, we just hope that we can make people feel welcome.”

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Tunde Adebimpe

Thee Black Boltz

Julien Baker & TORRES

Send A Prayer My Way

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE