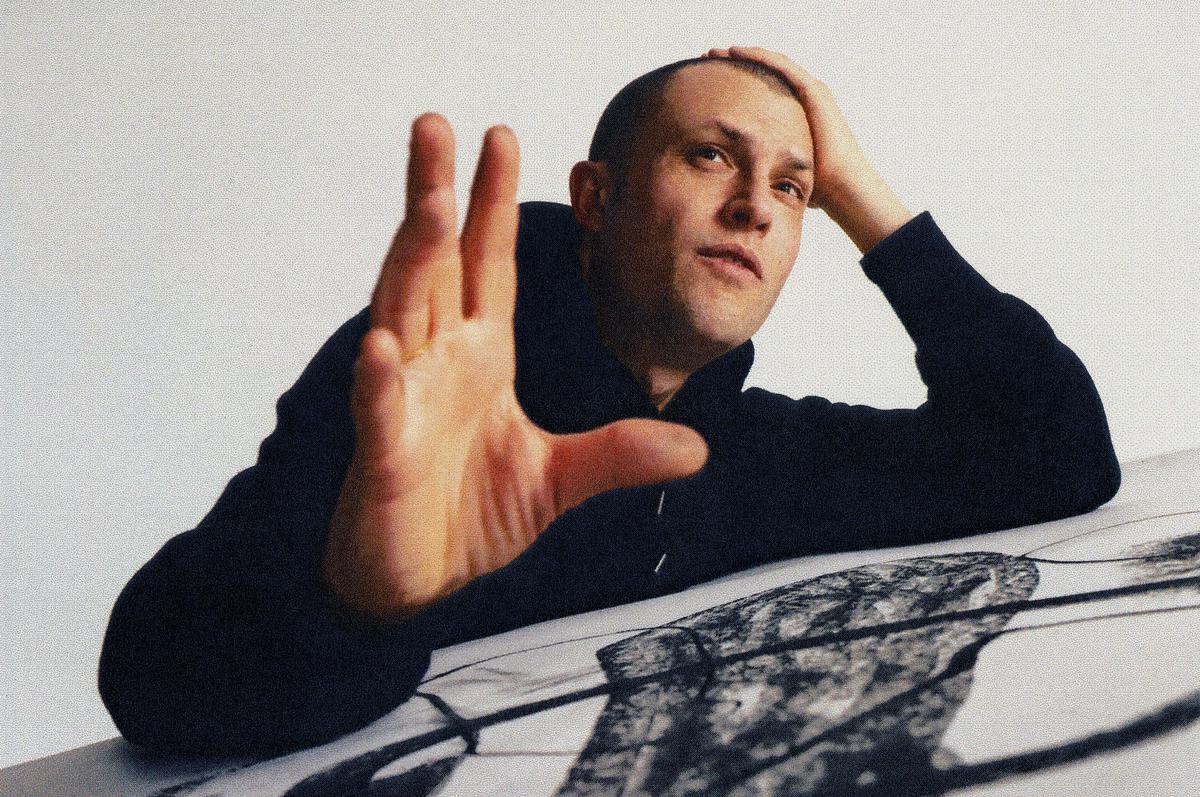

Orlando Weeks is caught between launch and landing

“I like that there’s a beginning, middle and end to making things,” Orlando Weeks explains over the phone from his London flat as the world begins going into lockdown on a more permanent basis.

“I always look forward to starting something new. The best bit of this job is the fresh start whether it’s an illustration or a new record. It was the same with The Maccabees - besides touring, the real gift of finishing an album was that we got to start something else.”

“After 14 years as a band we have decided to call it a day,” began The Maccabees’ message to fans informing the world of their split back in 2016.

Often the London five piece made the process of making a record sound unbearable. The group described themselves as “mildly traumatised” by the time they had wrapped up their final album Marks To Prove It. But that’s the price you pay for honouring a band so committed to its own democracy.

Judging by the sentiment they’d often use to describe the process, maybe their split shouldn’t have come as much of a surprise as it did. Although they were already sweethearts of the indie and alternative world, their third LP Given To The Wild went top five in the UK and scooped a Mercury nomination saving them from the indie landfill that so many of their peers fell victim to.

Marks To Prove It, released three years later, felt like a mature step further in the right direction choosing a more stripped-back approach to its reverb-drenched predecessor. It topped the UK album charts before they announced their split which was capped off with a run of celebratory farewell gigs culminating in three massive shows at London’s Alexandra Palace. Then that was it.

So, what happens when one of the band members finds themselves creating something that’s not constantly subjected to trial by an arduous decision-making process?

In Orlando Weeks’ case, he penned and illustrated a gentle Christmas tale about a retiring gritterman on his last night on the job. It was accompanied by an album of original material wedged between readings of the story by Paul Whitehouse. The project became an ideal vehicle for Weeks to explore endings like the one he was facing with his band at the time of writing.

The birth of Weeks’ first son in 2018 brought a heightened sense of renewal to his life which he subsequently poured into debut solo album A Quickening. “You’re a beginner / I’m a beginner too”, he sings on the opening track “Milk Breath (My Son)”.

Weeks has always been able to capture the tension between the ordinary and extraordinary. We touch on the Faraday Memorial which graced the cover of Marks To Prove It. “It was a photo from when it was first installed,” he tells me. “It looked beautiful - looking at that photograph reminded me to look at it in a different light, the current incarnation of it is the same one, it’s just had a renovation actually.

“It’s a different road system now so…” he trails off before conceding “god, that was boring”.

Even Paul Whitehouse once asked him, “who ever thinks about a fucking gritterman?!” in a Q&A about their project. His ability to elevate the mundane hasn’t waned over the years: “Gone the bell that has rung forever / At least as long as I can remember” he sings on “Bloodsugar” referencing the renovation of Big Ben which fell parallel with his son’s birth.

“A lot of the record is about the anticipation of his arrival really. I haven't sat him down and done a track by track with him yet,” he says with a chuckle. “All the finishing, fine-tuning and re-writing was done when he was there in the room or at the other end of the flat. I wonder whether there will be a time when he recognises it.”

"You have half the time you used to have and that changes the way you approach work a huge amount.”

“Milk Breath” begins with the lines “Lights out / Lay you in bed / Milk breath / Big dreams in your head”. Later on “St Thomas’”, named after the London hospital that both he and his son were born in, he recalls the flicker of life you can imagine appearing on a scan; “See those fingers start signalling / I walk down to St Thomas’ / I woke you up and saw you started moving”.

“You have half the time you used to have and that changes the way you approach work a huge amount,” he says on the impact of parenthood on his creative life. “It’s meant that I’ve had to be less sprawling in the way that I would usually approach something. I have to be more considered and better planned because otherwise if you don’t make the most of the time you do have, you feel it harder.

“But it’s also given me a much broader perspective on what I want to do, you know, rather than being proud of good work, there’s other things in life now that gives me a greater sense of peace.”

A beautiful palate of scattering drum beats, scratchy samples, piano and brass emerge throughout the LP. “I can’t play the trumpet very well at all but I can play single notes or basic stuff that I can turn into a kind of drone or texture,” he says. “On the whole what seems to work for me is sourcing a little list of instrumental characters which are now a part of my ensemble.”

Movement is at the heart of the LP from the song structures to the title and artwork. The music morphs and changes consistently throughout making for an enveloping, dream-like listen.

“I think everything is always in a constant state of movement, it's unavoidable. I liked that idea,” he recalls. “That notion of movement is maybe planted in your head by the title and artwork when you start the record. There's a lyric at the start of “Safe In Sound” that at one point I thought could be a cool title for the record - the line “caught between launch and landing”, I thought that captured the fact that nothing is still - not really.”

Weeks’ fascination with the constant state of movement is a clear testament to his introverted character. The cover of A Quickening captures the singer mid-stride trying to escape the pull of the lens: a blurred figure that sweeps across the frame. Bigfoot leaps to mind.

As frontman of The Maccabees, Weeks chose to simply play his part rather than indulge in band baiting or crowd-rousing antics. His new live setup sees him behind a wall of instruments in line with the rest of his band; opting to be part of the whole rather than front and centre.

Whatever his reserved tendencies might be, people continue to be incredibly drawn to his work. He sold out two runs of live shows in the past six months without releasing a single note of new music, the latter of which wrapped up a week before the UK was put on lockdown.

“With the Maccabees we must have played all the classic gig cities loads of times,” he recalls. “But to return to some beautiful venues I hadn’t played before and have a few hundred people prepared to sit or stand listening to the new songs was amazing. The stillness the people were able to give to the music and the night really blew me away to be honest.”

The Maccabees certainly attracted rowdy pint-slinging crowds, yet the music of A Quickening commands a more patient atmosphere. I wonder whether there were any surprises? “I think on the whole, people entertain you to begin with at least and if it’s not up there or not what they’re into then maybe they let you know or they leave. It felt like whatever they heard in the first ten minutes, they were prepared to buy into it. I felt super grateful that people were so patient with it in giving the music that sort of quiet, you know?”

The music on A Quickening frequently hits on a fresh and inspired sound. While there are traces of Radiohead, Arthur Russell and Talk Talk in the blueprints, it mostly remains uncomparable; there’s no whiff of a Maccabees-style riff at all throughout the eleven tracks. “St Thomas’” is underpinned by a descending piano sequence and swathes of restless percussion. Later, chirruping synths and sparse drum patterns split the warm atmosphere that shrouds “Summer Clothes” - “how bare a body goes”, he sings.

“That's one of the nice pleasures, finding just how far I can stray from what everyone else is doing without completely losing my place and blowing it. It’s a different kind of challenge,” he muses. “This sound is certainly a broader representation of my musical tastes. I think that throughout the record I’m trying to use my voice in ways that I haven't before, the same goes for lyrics and melody. I wouldn’t want to lose a lot of the things that I’ve learnt but I’m trying to be braver with the way that I approach certain things.”

One of the many instances where Weeks breaks new ground is on “Moon’s Opera”, the bones of which were originally destined for his side-project Young Colossus.

“I’m really proud of it as a piece of music, bits of it is me testing how free the vocal can sound over something quite structured which isn't easy for me,” he reflects. “Told tales all night / Of the fore and the after / Gotten older gotten wiser / Hallelujah / Lucky you are a rider”, goes the refrain.

The track was written as an accompaniment to sketches he would scribble throughout the pregnancy, some of which portrayed his partner and their son journeying through space and time together - he’s hoping to release them at some point. Music and illustration continue to be intertwining forces throughout his work, right back to the artwork for The Maccabees’ debut Colour It In which he designed and illustrated.

"You forget how many decisions you’re having to make until you're doing it, you know, making calls that feel like major decisions"

“I’ve really enjoyed trying to make something that is freer and the surrounding artwork for this record very much feels like an extension of the music,” Weeks tell me. “One of the major pleasurable cornerstones of trying to write a record is waiting for that glimmer of something that's worth further investigation. Piano has served as a good tool for that recently.

“It's such a luxury to have the time and space to just sit and try and do your ‘something out of nothing’ thing. I love trying to figure out how to make that work visually as well.”

Nic Nell, who also releases music as Casually Here was Weeks’ main collaborator throughout his first solo venture; adding his prowess to percussion, production and mixing in particular. It’s a much smaller troupe to the mechanics he’s usually used to.

“You forget how many decisions you’re having to make until you're doing it, you know, making calls that feel like major decisions. You end up feeling like you’ve made them a day after, they don’t feel like a quarter of the size that they felt at the time,” he explains.

“In terms of the making of the record, it’s a very different experience, you’re not having to concede on something you feel so strongly about on the seventh song on the record. I can’t imagine anyone that works in a band doesn’t accept the fact that you have to sort of pick your battles when it comes to mixes or recording. With this it's a very different thing, it's all on me.”

The lyrics on A Quickening range from the hyper-specific to the obtuse and refracted, particularly across the second half of the record. On “None Too Tough” he sings, “I want to dance with someone / Make a life with someone” before it unfurls into a dreamy daze: “If only retrospectively I was looking for a rainbow / They were cloudy days”

“I want it to feel...I mean I’m not sure exactly…,” Weeks says. “But I know that I’m trying to refine and understand why I like the look of something and the sounds of something. Just trying to be really honest with yourself about what your taste is...but also trying to not get stuck in it either. It's one of those things that the introspection of making work brings.”

In the worlds that Weeks can conjure in the flash of a mundane moment, our current circumstances could serve as a field day. He was, after all, the guy who spent an entire summer in Berlin writing about a retired gritterman in the South Downs at Christmas while everybody else around him lined the city’s canals with a drink in hand before partying into the night.

“Well my one-and-a-half year old keeps me pretty busy,” he laughs. “We’ve just finished listening to the Gone Fishing audiobook [an accompaniment to Paul Whitehouse and Bob Mortimer’s TV show]. There are really funny bits but because he loves fishing Paul can’t help but let the teacher in him come out. It’s quite an earnest pursuit so suddenly he slips into that, it’s funny just hearing that tone in him. From working with him a bit, we all know how much he likes to keep everyone entertained but then there’s this flash of another part of him.”

Besides illustration and music, prose has become a more prominent entity in his creative output that he’s looking to expand further as well. “I definitely want to return to it. I’ve almost finished something about a sculptor which I’m really happy with. Once all the odds and ends of this are finished and obviously depending on what happens in the world, I think that's something I’d like to get into and find homes for.”

It seems Weeks finds solace in having a multitude of projects caught between launch and landing. But as he suggests throughout our conversation: it’s a process we’re all part of in some way or another.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex