A paradise of experience

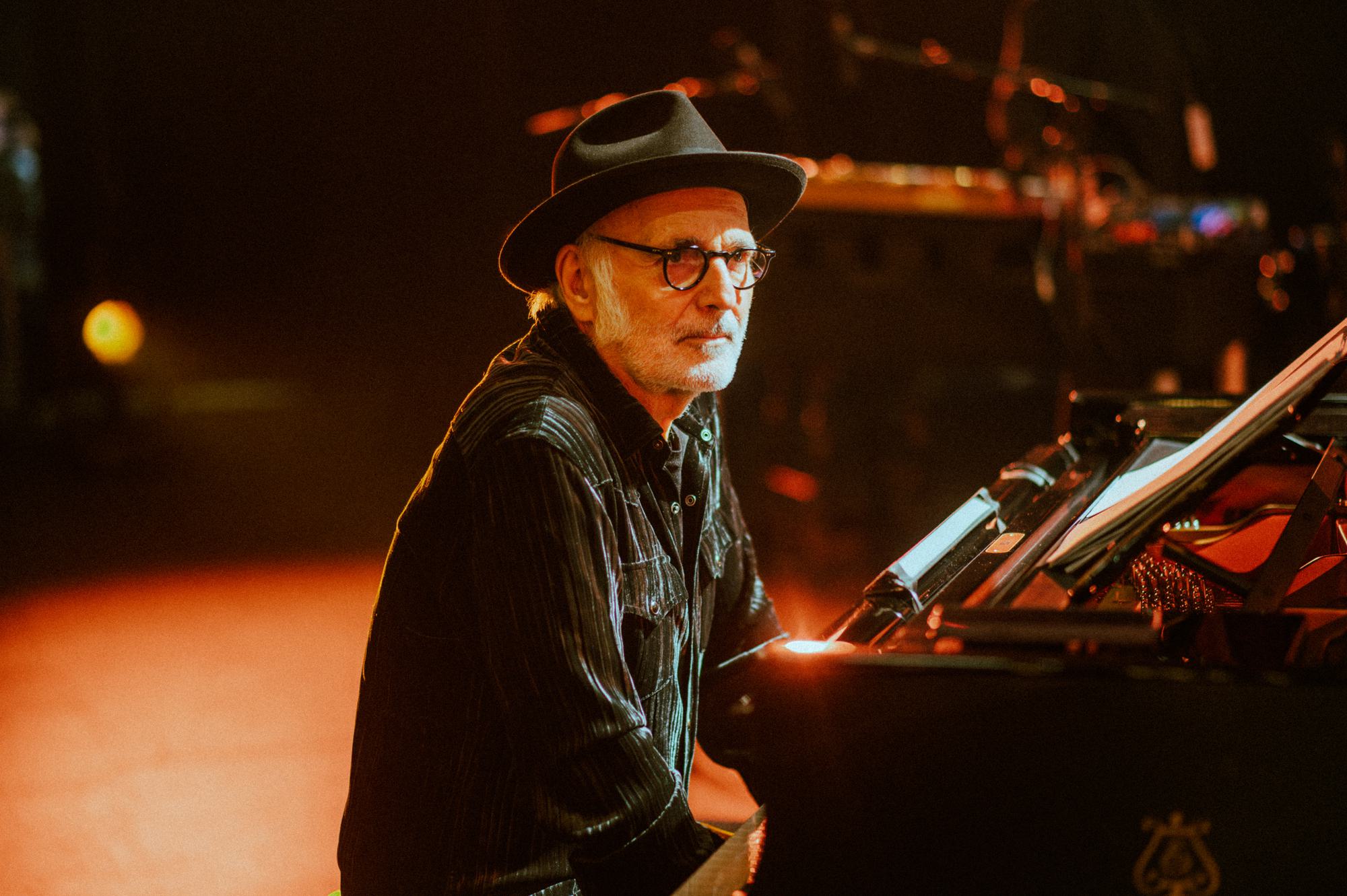

Channeling a remembrance of summers past into his new record Summer Portraits, Ludovico Einaudi tells Sophie Leigh Walker about music as salvation.

Memories had started to tug at Ludovico Einaudi’s shirt sleeves as he sat down at his piano in the summer mornings.

The keys started to sketch out soft remembrances: his childhood holidays spent by the cyanic blue of the Tuscan Archipelago where the water was so clear he could spy the seahorses, of riding his bicycle barefoot at sunrise and not coming home until sundown; his mother, the first to play piano to him as a child, listening to records on idle afternoons.

And there were dreams, too - the music starting to colour the imagined life of his grandfather, a man he never knew, who left his family to escape fascist Italy and began anew in Australia. Summer Portraits, the latest album from one of the most beloved and instantly recognised composers of our time, does an impossible thing with ease. Einaudi restores what we believed was lost to us; his music gives shape to our lack and grants it presence. And he does so without saying a word.

Understand this and his success should come as no wonder. His music gives space for stories that only your own mind can tell you. Einaudi is everywhere - so much so that you may have not noticed the way his compositions have become a natural part of experience. His scores have underlined the dignity to the social portraiture of Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland and Shane Meadow’s This Is England, where his music sits in the company of Madness and The Jam; his own material has lent itself to endless trailers and commercials, and TikToks of his performances regularly attract views in the millions. Listen those gentle opening whispers of “I Giorni” – a track with the unusual distinction of entering the UK Singles Chart ten years after its first release – and you will walk down a path of instant recognition and remembrance.

Einaudi’s compositions are among the first a young pianist will learn. They are simple, as the truth often is, and through spirals of repetition and subtle turns of elaboration his pieces articulate our most tangled emotions. We are lighter for having listened. Though his discipline is rooted in classical music and Milan’s Conservatorio Verdi, Einaudi’s instincts are those of a pop star. He observed the rules and politely declined them - and while the establishment might shun his work, the rest of the world has wholeheartedly embraced it.

“The inner clock started to have an effect on me,” Einaudi tells me from his home in Torino, the town where he spent his childhood where he has now, at nearly 70-years-old, returned. He is always writing at his piano – in fact, he had only just been working on new material this morning. But the songs that would become Summer Portraits stood apart because he felt them to be in conversation with time, bound together by age’s desire to breathe life into an irretrievable past.

One August, Einaudi had been renting a house by the sea with his family on the Tuscan island of Elba. He has a way of describing things with almost painterly detail; he tells of how it was surrounded by a forest of pine trees, and the vista of the ocean and Monte Cristo in the distance. In the bedroom, there were a series of six paintings on the wall made of oil and wood, decidedly different from the impersonal artwork you expect in holiday rentals. As he explored the other rooms, there were more of these paintings all made from the same hand which captured the property’s view for every passing summer. “I was curious, and the next day I asked the owners what the story was behind the paintings. They told me that in the 1950s it was owned by a family and each year, the mother would paint and leave them in the house. It was a simple story, but it sparked my imagination and I started to reflect on summers of my own.”

The music video the album's opening track “Rose Bay”, which sounds like the tender unspooling of memory itself, is of intimate holiday footage from his boyhood. There is Ludovico as a child, pulling his mother by the hand into the sea; squinting in the sunlight with a mane of dark hair, building sandcastles on the beach. “Summer is more than a season, it’s a season of your life,” he shares. “In the summers of my childhood, I discovered all the most beautiful things. Because first of all, there’s the light – it lasts from early morning and arrives at late evening, and there’s no school. You’re free to play with your friends all day long in a t-shirt, shorts and no shoes; you’re riding your bicycle and feeling the wind.

"You’re swimming, falling off your bicycle, and even though you’ve hurt yourself you’re happy anyway. You have your best friends - and you would do anything for your friends. You maybe meet your first love and taste the exquisite food from the farmer who grows his vegetables and the fisherman who brings fresh fish from the sea. It’s a paradise of experiences. The rest of the year was about living in the city, going back to school and coming back to darkness. But the other time was freedom.”

Summer Portraits started to take on the form of memoir. “It’s a very beautiful effect that it creates,” Einaudi says, “because sometimes you smile, and sometimes all you feel is the loss of those moments. My childhood was happy and without many thoughts. Boys tend to be like animals, in a way – they just like to play, like little cats. I enjoyed very much being an animal in that part of my life. And then there is always a moment where you lose the magic…”

He describes, then, what we all eventually must experience: adulthood and our exile from that early paradise. “You lose your self-confidence, and suddenly you are unsure of everything,” he reflects. “You don’t know what your life is going to be, you don’t know if you can do what you desire to do – and so begins a slow process of rebuilding that confidence which is hopefully connected to doing what you love. I was lucky to find my place in music, even if at the beginning I didn’t think it was going to be my life’s work as it is now. I was dreaming, I was hoping, but at the same time I had to face the outside world – and it was not easy at all.”

Einaudi finds himself reaching for simplicity, whether it be a recapturing of the freedoms of childhood in memory or in the lucidity of his music. “It’s not just romanticising the moment. It really was beautiful,” he insists. “Life was simpler and slower, and so we were very connected to the time we were living in. The village was not yet destroyed by humans. As a child, I didn’t know about the dark side of life. Everything was perfect.” On the track “To Be Sun”, he leans into the joy of its light but acknowledges that it must always set. “There’s nothing of that magic anymore,” he says. “There are very few details remaining from how it was. The landscape changed; the seahorses are no longer there.”

Reminiscences of childhood led to ideas exploring the figures who dominated his early life and the absences he felt keenly. “Maria Callas” is named for the American-Green soprano, but really, it is an ode to his mother Renata who would always play Callas’ music in the family home. She was an amateur pianist herself, and her “delicate” style of playing left an indelible impression upon young Einaudi.

Recording the song’s earliest brushstrokes on his phone, it was only after the fact that he realised the geotag was linked to Allée Maria-Callas in Paris – the street where the singer lived and died. Fortified with cello, Einaudi wanted to channel the air of opera and the unbound emotion of the prima donna who soundtracked his earliest years.

“Rose Bay”, however, was inspired by the grandfather he never knew. Waldo Aldrovandi was a prestigious opera conductor who performed for Puccini and received dedications from Prokofiev – but he left Italy, and his family, in protest against the country’s fascist government in the 1930s. He emigrated to Australia when Renata was only twelve and never returned, eventually starting a new family. Though he wrote letters to his daughter for the remainder of his life, plans for reunion always fell through; the next time she would be with him was at his funeral. “I was born with a boomerang in the house and a didgeridoo she brought back with her,” Einaudi shares. Since then, he has connected with his Australian family and took the opportunity to visit his grandfather’s home in Rose Bay following his performance at the Sydney Opera House. The song was spirited to life in his dressing room where he looked out onto the boats in Sydney Bay; those chords where the opening chapter in his vision of what his grandfather’s life was like there and a homage to the man he never knew.

Einaudi’s decade-spanning tenure belongs to a wider phenomenon which exists on the fringes of classical music. One might describe it as “postminimalist,” “ambient,” or “neoclassical,” gesturing toward the soulful simplicity he shares with the likes of Max Richter and Nils Frahm. Their melancholic repetitions and water-coloured arpeggios have been technically mocked, with The Guardian reviewing Einaudi in 2019 as having “the balladry of Westlife but without their clarity of purpose”, but each composer has reached astonishing popularity to the point that they get along just fine without critical approval. Einaudi’s style has led him to an audience of 8.1 million monthly listeners on Spotify – more than any classical performer, dead or alive.

“I like the idea of being essential,” he explains, “of creating a skeleton of the music that is maybe minimalist – made of small things that, when you balance them together, create a strong effect. The purest of things… If you look at the flower, there’s simplicity. Of course, simplicity can contain complexity – but for me, arriving at a work of art you can understand immediately and leave you with a strong effect is the goal I strive to achieve. Think of diamonds: they don’t need anything more than what they are. This is something I have always seen in popular music, because popular music doesn’t think too much. It’s immediately connected with the emotional need to say something, and I think that direct connection makes it beautiful.”

"I like the idea of being essential... of creating a skeleton of the music that is maybe minimalist – made of small things that, when you balance them together, create a strong effect."

As a teenager, he was under the tutorship of the Italian composer Luciano Berio – a pioneer of electronic music –who introduced him to African vocal music. He has been drawn ever since to native music on a global scale. 2015’s Taranta Project drew from North African and Turkish folk as well as a revival of the ancient songs of the Salentinian tradition which were once used to drive away the devil. “These people have an incredible connection with their roots and the past, and I’ve been trying all my life to keep that purity and grab it whenever it appears to me,” he says.

Nevertheless, the classical world he entered into as a young pianist was bound by stricture and tradition. “It was a world of rules,” he reflects. “In the beginning, I wanted to learn those rules and understand why they existed. I didn’t question whether it was good or bad to follow them, but I needed to understand how to play by them. But there was a moment where I learned what I needed and I realised that the classical modern world was not my world. I thought, ‘Okay, I don’t need this anymore’ – and I started to follow my own instinct. I didn’t want to abandon the music who made me who I am.”

Though his childhood was soundtracked by Maria Callas and Chopin, he was also absorbing another range of expression from The Beatles to Jimi Hendrix. His music shares in their chart-climbing qualities just as naturally as it parallels the techniques of the conservatoire. “I didn’t want to say, ‘Okay, I’m a grown up now and I have to be serious and write music a certain way’ – because this cannot be done,” he explains. “I wanted my music to reflect the world I was living in and to be completely free and open to experience. I decided I didn’t want to follow any orders, so I went my own way. The classical world then started to turn their backs, and I was in a way abandoned by it. But I didn’t feel at all lost. I started to have a strong conviction that I was doing something that was right for me. I had to make a living because nobody was calling me anymore, but I was at the beginning of something interesting. There were no streets where I was heading. It was like a desert. I was trying to understand which direction I could head in and how I could define the roads.”

I wonder if Einaudi felt fear as he was cast out of the world he was trained to live in, left to navigate an uncharted world in which he felt entirely alone? “It was scary, but I had a different connection with the people,” he notes. “Before, when I was in the classical world, I was seeking a connection with the establishment and the critics. But after, I felt like I was closer to people and the rest of the world – and it was far more comforting.” He reflects on he was living in a cottage in Milan in the springtime; the windows and doors were flung wide open on the ground floor, and as he played the piano, passersby would stop their own journeys to listen to his music. “This would probably never have happened if I was playing the music I was trying to create before because it was more abstract, and it wasn’t connected with my soul,” he says. “The confidence I had to play the music I wanted to make started to resonate with people.”

Sometimes, Einaudi feels as though it is difficult to comprehend what he has created. The roads he has made in that once-barren desert are now sprawling, and as people venture into his world, they are finding their own paths which have never been before travelled. “I only understand the quality of what I’ve done months, even years, later,” he says. He recalls an instance when he was composing music for a ballet, and as he was sat at the piano in an empty theatre, sketching as he always does, a woman stopped working and mustered the courage to tell him: “I’ve been listening to your music every day, and I wanted to say thank you.” He tells me, “This one episode represented what I’m trying to tell you. The words from that lady were more important to me than all the figures of theatre in the world. It came from an honest, instinctive reaction. I feel the more I go on, the closer I am to the freedom I’ve always been searching for.”

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex