Perpetual motion

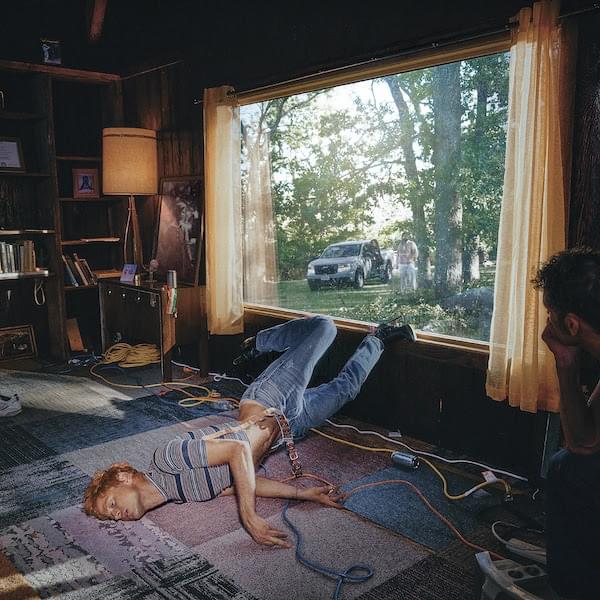

On the release of his new solo album, Turn To Clear View, Ezra Collective's Joe Armon-Jones knows one thing for sure: jazz should never stand still

For a long time, the word jazz meant a few things: Fedoras, fusty old rooms, chin-stroking. It had become, for want of a better word, a bit cringe (see the Mighty Boosh’s bebop obsessed Howard Moon for reference).

In the past few years, though, something has changed – jazz is cool again. Youth, that state prized above all in popular music, has commandeered London’s jazz scene, but with that has come a lot of misconceptions about the music. Joe Armon-Jones – one fifth of Ezra Collective, and a pivotal voice in this now-established artistic community – wants to set the record straight.

“There’s a lot of talk about ‘Oh, these people don’t stay true to the tradition’, but what I don’t think people realise is that the tradition of jazz is to innovate. Every time people push forward there is a wave of criticism, and then gradually that will kind of recede as people realise that it’s the new thing and they’ve got to get on the boat or be left behind. These things can’t be forced.”

The pianist is endearing when we speak on the phone, in a laid-back, slacker sort of way. While he’s grateful for the praise that I can’t help but bestow upon him, there are moments, like this one, that feel almost combative, betraying an inner steel that feeds into his musical philosophy. He is particularly adamant about quashing the widely held view that this new generation of musicians are ‘ripping up the jazz rule book’.

“Jazz is just an empty vessel, and people apply meaning to it,” he says. “The tradition of the music is actually to adapt to the social and political environment, everything which is going on in the world at that time. I mean, you could even argue that playing music from the 40s and 50s now would be to go against the tradition, because you wouldn’t be playing what’s true to yourself. We are playing the tradition, everyone is, because everyone is playing the tradition of making improvised music based on their surroundings.”

No great musician, jazz or otherwise, has ever remained shackled to tradition, and Armon-Jones says that London’s new jazz players, who fuse hip hop, Afrobeat, R&B and funk into their sound without prejudice, are merely following suit. This genre fluidity probably explains why the scene has been able to flourish so freely, and how artists, Armon-Jones most definitely included, have been so prolific. His new solo record, Turn To Clear View, follows last year’s Starting Today, a 2017 collab with Maxwell Orwin and four releases with Ezra Collective in the past three years alone, not to mention countless other guest spots.

Referring to artists’ careers as a ‘journey’ is pretty hackneyed, but it definitely fits here. Starting Today is all in the name: it’s Armon-Jones’ statement of intent, his first steps as a solo artist. Turn To Clear View, then, sees him stretching out in a full stride, his voice found and production experimentation in full effect (listen out for the soundscapes layered in between every track). He’s in a very good place, which has certainly been helped by his strong musical grounding. That all started in a small town “in the middle of nowhere”, somewhere near Oxford.

“I’ve been playing piano since I was about seven,” Armon-Jones tells me. “My parents are both musicians – my dad is a jazz piano player, my mum is a singer – so I picked up a lot from them. It means a lot to see people who you look up to enjoying something, and then if they enjoy it, you see that you can enjoy it too”.

In this sense, Armon-Jones’s musical background is pretty typical of the best jazz players: it’s hereditary. Music, he tells me, was always going to be his path: “It’s one of them ones like natural selection, because I wasn’t really that good at anything else. I never really took to any other subjects, so it became pretty obvious to me that music was the one thing that I was interested in and that I enjoyed enough to follow.”

The maverick image that Armon-Jones unwittingly fashions for himself is only bolstered by his, let’s say, scruffy look. Instantly recognisable wherever he’s playing, Armon-Jones is a mess of unkempt curly hair spiralling off at all angles, a cartoon professor receiving a static shock. When he’s off stage, the image is relaxed, careless even, but when he’s behind a keyboard – cogs whirring, eyes darting, fingers moving between sumptuous chords at lightning pace – he has the speed of thought and the calculated precision of a scientist in the lab, and the alchemy he achieves between every member of his constantly evolving band always brings forth a delicious elixir.

After catching the jazz bug from his parents, Armon-Jones developed his talents, like seemingly every young person playing jazz in London, at Gary Crosby’s famed music school, Tomorrow’s Warriors. “I just came to London and didn’t really know anyone,” he remembers. “I was just looking for people to play music and chill with. I think a friend of mine who wasn’t even going to Tomorrow’s Warriors said, ‘Ah, you should go to their Saturday class.’” Armon-Jones did just that, turning up to his first session in predictably casual fashion. “I got there when it said it started on the website, but no one had told me that the times had all changed, so I was waiting there for hours. Then, thankfully, people started to show up, and that was it. Definitely life changing, I think.”

Fans of jazz will be thankful that Armon-Jones decided to stick around and wait, as it was at Tomorrow’s Warriors that he started working with most of the people he still collaborates with today. “I met most of the people in Ezra there, Nubyah [Garcia], Theon Cross, David Mrakpor...” I spoke with David Mrakpor (Mr. DM when he’s one half of Blue Lab Beats) for a piece recently, and he too was quick to eulogise about the institution. It really is a fascinating case – an organisation that doesn’t just foster talent, it has brought together most of London’s current youthful scene. As the nucleus of this new wave, its influence may well one day be talked about in the same breath as Chicago’s AACM, or New York’s finest conservatoires.

How has Tomorrow’s Warriors shaped London’s new sound? Armon-Jones puts it down to director Gary Crosby’s unique pedagogical philosophy. “Gary is very good at identifying one thing that someone can do really well, encouraging that, then showing the other things that they can’t do so well. But he instills the self-belief for you to continue and get better at the other stuff.” It’s an approach Armon-Jones thinks is missing at many of the UK’s traditional musical institutions, whose classical tendencies, with a focus on sheet music and strict adherence to precedents, does not engender the freedom of expression and unbounded creativity that a proper jazz schooling requires.

“I think it’s just quite difficult to… whatever the word is, curriculumise jazz,” he says. “To put it into boxes: you’ve got to learn this in this term, then you’ve got to learn that in that term. It’s really difficult to learn something if you’re not interested in it, and that doesn’t just go for jazz, but it’s especially obvious there. If someone doesn’t want to learn swing or how to play bebop phrases, but they are made to feel like they have to, then you can hear that in the way they play. It’s kind of sad to hear that. The most enjoyable thing about music is hearing someone play the thing that they were meant to play, the thing that they want to play. Tomorrow’s Warriors was very good at encouraging that.”

Gary Crosby’s model creates great jazz players: that much we know. Armon-Jones thinks a big part of how Crosby has achieved this is by not confining jazz to any sort of definitions: “They were always playing the greats, like Duke Ellington and Charlie Parker, but that stuff can be celebrated without stopping any future development of the music. It felt like a really good environment, where you could come in and talk about whatever you listened to last night – a Wes Montgomery record, or whatever – and people can understand that and dig that with you. But then you could also come through with a Dilla or Madlib beat, and you wouldn’t get laughed at, like ‘Why are you not trying to play jazz?’ They understand that it’s all just music.”

One look at Armon-Jones’s output and you can see he stays true to this eclectic maxim. His oeuvre is as likely to contain hip hop and grime – see “Ragify” on Starting Today, or “The Leo & Aquarius” on the new record – as expansive, Ellington-esque piano solos. “Philosopher II”, on Ezra Collective’s most recent offering, You Can’t Steal My Joy, is in that most classic of veins, an electric tour de force where Armon-Jones takes his instrument to task, coaxing out wild new timbres – like a neat strum straight on the piano strings – in a seamless, unending melody. It’s a break, in fact, from his normal style, which is more predicated on opulent chords, tight grooves and witty, inventive improvisation.

Armon-Jones goes on to cite a long list of pianists who have nurtured his musical development. “In terms of piano players: Oscar Peterson, Ahmad Jamal, Bill Evans, Nina Simone... There’s an album by Chick Corea and Bobby McFerrin called Play that was particularly influential on me too. But nowadays I’m quite open with what I will listen to, because I’m not having to sort of learn things for rote like I used to have to. So you end up being more wide-ranged, you know?” Eclectic his influences certainly are. Those greats are mentioned alongside electronic pioneers like Theo Parrish and DJ Rashad, showing a diversity of taste that is clearly a product of Armon-Jones’ musical education, but also due to the company he keeps.

He tells me he got onto those electronic styles under the tutelage of his housemate and long time collaborator, Maxwell Orwin, a DJ and producer who, along with Armon-Jones, ensures their household is a constant hum of musical activity: “There’s always someone making tracks, man. There’s always at least one session happening in the house, or someone making a beat or someone singing.”

The constant presence of other creatives – and the cycle of creation that jamming with them precipitates – might sound like hard work, but Armon-Jones doesn’t think so. “I mean, I don’t even think of it as ‘working’ with people in a normal sense,” he says. “There’s so much collaboration happening and there are so many people crossing over on projects all the time. You kind of get used to it really, just having people around that share skill sets. It’s nice.”

Some local artists who Armon-Jones wants to shout out include Wu-lu, Kwake Bass, Lex Amor and Rago Foot, all “creative geniuses” in their own right. The new record sees Armon-Jones team up with a number of frequent collaborators too. Moses Boyde, Nubyah Garcia and David Mrakpor all feature, while new voices, like the Nigerian-born, London-based singer Obongjayar, join some of the most important and established names worldwide – LA based singer Georgia Anne Muldrow being the pick of the bunch. “I met her when she came to London,” Joe recalls. “I just gave her the Starting Today record and mentioned that I had a track that I would love for her to sing on for the new one. She said, ‘Sure, send it through.’ So the next day, when she got back to America, she just holla’d and said she was in the studio, so I sent over the tune. And yeah, she smashed it out, man.”

Producing this much music and working with all these prestigious artists (not to mention the never-ending circus of ‘hype’ that goes with it) would be enough to get into some artists heads: the pressure to release, release, release affecting their creative output. But Armon-Jones is quick to dispel the idea that he is distracted by a musical commentariat obsessed with ‘the scene’ or various things ‘blowing up’. “I don’t think anything about it man. I just keep going, making music. If you start getting distracted by those things then you get lost.”

Immune to the pernicious effect of widespread praise, Armon-Jones sticks to what he knows, and improvisation is at the heart of it all. Jazz, like theatre, is defined by its live aspect: each performance is a fixed entity, a common, shared experience captured at a moment in time. While it’s difficult to retain that aura in the context of an album, Armon-Jones tries to recreate it as much as possible when he records. “I keep that [live aspect in recording] by not giving the musicians the music until the day of the session,” he says. “So when the musicians come to the recording session, that will be the first time they see the music. They have to improvise and they have to be right there on the spot. There’s no rehearsing, we just go in and do it. We’ve just got to look at the vibes, look at whatever we’ve got written down and make something off that. But there has to be improvisation, I’m relying on people to bring that to the table, otherwise the tunes will sound empty.”

The notion that you can stroll into the studio and bang out pieces as accomplished as “Mollison Dub” or “Yellow Dandelion” with little prior work sounds unbelievable, but Armon-Jones assures me it’s how he works: “I took like a week or something to write it [Turn To Clear View], but it’s not even really like a week of intense writing sessions, it’s just me sat around in my boxers and dressing gown at home, chilling. With the kind of music I make you don’t need a long time to write it. You just need a few chords, a tune and a bass line that you’re happy with. You don’t know how it’s going to sound until you actually play it with musicians anyway. I just write ideas, sketches, things that I think might sound good. I’m never 100% sure on anything until I hear it with the band – until then, it’s just sketches.”

Can this be true? Is making music this consistently good really that easy? Well, perhaps: when improvising is at the core of your music, there is always going to be an off-the-cuff feel to it that appears as nonchalance to the outsider. What Armon-Jones omits is that, as a musician, he is in a constant process of honing his craft, both alone and through his work with other musicians. His process, whilst ostensibly relaxed, has a very deliberate purpose – thanks in no small part to the years of practice behind it.

However, all that quiet study will never come at the cost of the live gig, where thinking on your feet is not just a gimmick but a necessity. For Armon-Jones, the here and now is everything. “Improvisation is the key thing for music – it filters through into all kinds – but it is definitely the key thing for jazz,” he says. “I would argue that if everything that happens is exactly the same at every single performance, if nothing is left up to chance, if no one makes anything up or creates anything new on stage, then I would argue that it’s not jazz, the word can’t apply.”

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Great Grandpa

Patience, Moonbeam

Deafheaven

Lonely People With Power

Perfume Genius

Glory