Yin and Jung

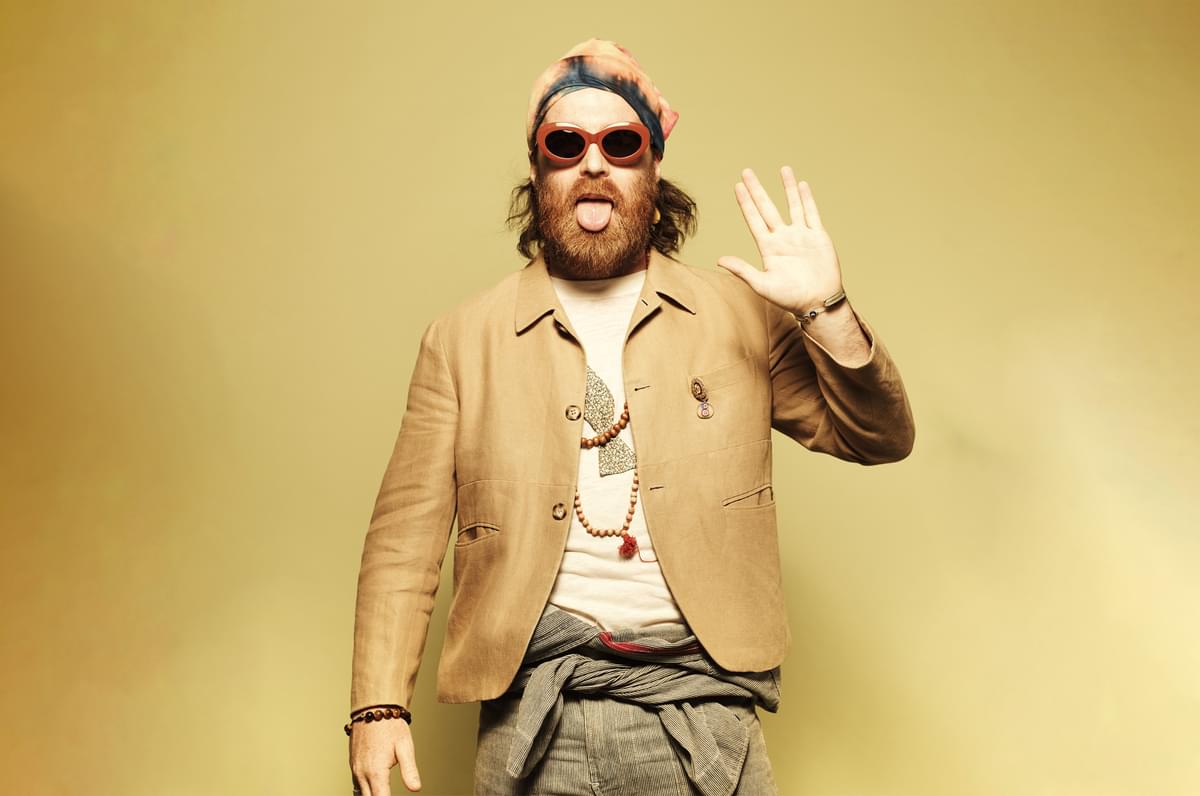

After experiencing philosophical clarity, Nick Murphy resurrected his Chet Faker project and allowed himself to feel good.

In 2016 Nick Murphy dropped the moniker Chet Faker. But after a difficult year on the road, the loss of his father and the onset of lockdown, Murphy turned from the shadow world of his eponymous project and back to the light of his alter ego, choosing to find joy and hope in life and creating bright and optimistic new album Hotel Surrender.

“It's more like a Jungian shadow type thing,” explains Murphy from his small New York studio amid a sweltering heatwave. He’s assessing the differences between his two projects which now exist congruent to each other. “The Nick Murphy shit for me, it's like shadow work, it’s earthy, it's raw. There's no soft edges. It's not Disney, it's not the positive outcome, it's the negative process. It's European cinema versus American cinema. If I wanted to really lean into some uncomfortable energies or themes, that's usually when I'm like, this is a Nick Murphy release. When I might need to do a ten-minute improvised instrumental piano piece that’s just pure catharsis, that's the Nick Murphy shit. Nick Murphy's earth and Chet Faker is sky.”

The Nick Murphy project had been his focus for over half a decade. Putting the electro-soul of Chet Faker aside in 2016, he focused on the darker, more introspective side of his art, releasing a string of singles and EPs which culminated in 2019’s Run Fast Sleep Naked. For Murphy, it allowed him the freedom to express himself, even if it wasn’t his glossiest side that was coming out. “I think one of the biggest misconceptions people make about the creative pursuit or creative output, is that you're supposed to always make good stuff,” he muses. “But that is not it at all. You're supposed to always make stuff, and for every good thing you make you're also supposed to make shit stuff. This is just some corporate, capitalist view that’s seeped into our creative mind that it's supposed to always be good. But it's not.”

Thoughtful and eloquent, Murphy is warmly sardonic, musing on the greater questions that surround his life pursuit. It’s hardly surprising that across his career he’s refused to follow the path laid out for him. “To create is just to express. Where's an artist supposed to put all that murky, gunky stuff, you know?” he asks. “I know. Usually they just keep it on their hard drives and it sits there and festers like a pool of darkness, this little shadow imp in the corner of the studio that just says nasty things about them. But for me, I was like, well, this is a true part of my process. So I don't want to deny this. And I want to share this, because sometimes I hear artists that share this raw wet clay of music, and I like hearing it.”

Murphy arrived with much fanfare in 2011 when his cover of Blackstreet’s “No Diggity” blew up across the blogosphere. It was a time of fan-curated music discovery, mp3s and Hype Machine, and it catapulted Murphy into the spotlight. It was also a period he looks back on fondly. “It was the last time that the internet wasn't funneled by corporations or major apps. It was the last time it was user driven,” he says. “It was exciting. We had to find music. If your friend gave you a good blog to follow, it’s like this whole new source of music coming in. I genuinely miss Google Reader. The internet was so good then. I say to people all the time, the internet peaked at Google Reader. Once that was gone, we lost the ability to filter, and have a raw, unadulterated, unadvertised version of the internet. You only got what you wanted from sources you wanted. You can't do that anymore.”

However, Murphy’s ascent was too quick for him to ever take a breath. Within a year he was signed, touring the world, recording and releasing music and winning awards. “It was really fast, that's for sure. It was really fast and it was really organic, which is like a weird combo. It stressed me the fuck out, it blew up so quick,” he says.

With elation came claustrophobia, as Murphy struggled to find room for a little perspective. “Certainly one of one of the driving forces for me putting the Chet Faker project away was the need for space,” he explains. “I'd had this massive thing built around me, and at the ripe young age of twenty-five I was like, I don't even know who I am. I want to live a real life. I don't want to end up like some of these musicians that talk about themselves in the third person and shit. The grandness of the success and growth made me a little uncomfortable. I made a commitment at a young age to music and to the creative process, but I began to question that. It's easy to say it's all about the music when you're underground, when you're not famous. It's the easiest shit to say. I wanted to prove to myself and to others, but to myself mostly, that I wasn't afraid to lose this.”

For Murphy, that space came with a name change. In leaving behind the blue sky shimmer of Chet Faker and delving deeper into the earthy dark side of his feelings, Murphy found the balance he was craving. Now with the benefit of experience, it’s much easier to see how his two sides can work in harmony. “Almost anyone under the age of 30 knows what a Finsta is. It's normal to have multiple digital selves,” he shrugs. “I think as this digital world begins to become very real to a lot of people, we also begin to understand that we are in fact more than just one person, we are lots of different people.”

It’s an engaging philosophical concept to believe that we exist in more than one place at any given time. The internet has enabled us to create versions of ourselves, many small and curated imprints accessible at the tap of a screen. “You know why I think that is? There's less time for people to consider things,” says Murphy. “So that means when you do a thing, at least digitally, you have to say what you're saying very quickly, very succinctly, right? So that means we lose the intricacies and the ripples of the impression of a person. So you become more singularised as a person when you express yourself digitally. But there's all these different versions of yourself in you. So it's almost like we're picking the main versions of ourselves and just doing multiple ones, because one can no longer represent them all.”

Murphy spent most of 2019 on the road touring Run Fast Sleep Naked. As well as the pressures of a baseless, transient life, the world was throwing him a relentless barrage of challenges to deal with. ”Twenty-nineteen was one of the hardest years of my life, actually. It was really a really bad, hard year, really, just so much shit was happening,” he sighs. “All these people were trying to sue me for shit. It was literally like the universe was just like, fuck you. It was literally just like day after day. I lost all this weight. I was super skinny, just from pure stress.”

Returning to New York in January of 2020 after two years without a home, he found an apartment in Chinatown and rented a small studio space nearby. He had no idea what a welcome relief settled stasis would bring. “I hadn't had a studio since I moved to the States. And it was like there was this banked up stuff that hadn't been able to let itself out,” he says. “I started coming in here every day and it was just like this dam had been broken. I was writing like three songs a day. I had my little life. I finally was still for a minute. I wasn't touring. I was just vibing. I was just making all these songs, and I wasn't trying to make a body of work or anything. I was just coming in and enjoying having a place to go, this little room on my own where I could just plug all my toys in and make some noise.”

The space which came with his new found calm enabled Murphy to focus on his own wellbeing and mental state. “The thing is, when you're really faced with challenges, like really under a lot of pressure, it's easy to realise that you can choose to be happy. Which I know sounds ridiculous, but sometimes only under the most pressure can you truly realise that you have a choice in how you're going to feel, in a sort of manic way,” he explains. “You can just be like no, today I'm going to lean into this and whatever is happening is happening. I'm not a victim, I just am, and this is life. I'm alive and I've got to apply myself.”

Murphy started 2020 with a new positive outlook, working on music and like most of us, oblivious to the turmoil quietly making its way around the world. “I started writing this record and all this really happy stuff was coming, it was totally from a place of joy, and expression, and I was just enjoying making it,” he smiles. “And then Covid hit, right in the middle of making Hotel Surrender. And I was like... whoa.”

As the universe removed any distractions, Murphy hunkered down and kept working, and by May he had enough tracks for a record. But as he began to add the finishing touches, he got news his father had passed away. Murphy describes his father’s death as sudden and random, the shock galvanising him to dig deeper into the positivity of the music he had created. “I was already on this trip of like, your life is happening right now. It's right in front of you, and you've got to bring the energy and attention that you want to it. You can't wait for permission or the external fields around you. You've just got to create every day,” he explains. “When my dad just passed away, that really contextualised it. I was like, holy shit. Like, this is it, this is life, this is temporary. It's all temporary. This whole record is a real lesson for me, that this is it, it's just what's in front of you.”

When he finished the album last summer he took a step back and realised he’d made something light, hopeful and joyous. Creating the music in a similar style to his earlier work, locked in a small studio completely alone, he recognised who the album belonged to. “I'm like, well I just put Chet Faker away, but I had this record that really helped me through some difficulty and I know from experience that when music has helped me with something, it often translates to those that listen to it,” Murphy shrugs. ”I felt like I had a tool for processing things at a point where the world really needed help. You know, whatever, it's just music, but I felt this kind of weird compulsion, and even my dad would certainly have thought the same. It's like, just give it to people. Just give it to them because it's kind of positive and don't overcomplicate it. It felt like a gift that I've been given and it would be selfish for me not to share it. So that was what drove the return of the Chet Faker project, was this new realisation of what it was and what it could be. And that's kind of how I approach the project now, as a sort of positive force.”

"For this particular record, not just musically but philosophically, life-wise, what's in front of me is good enough. And that's it. That's the purpose."

The album also marks the first time Murphy has included the piano in any Chet Faker music, despite holding a lifelong passion for the instrument. “Piano was such a part of my DNA. I just have this relationship with piano that I don't have with any other instrument,” he smiles. “When I'm really playing piano, I don't even know what I'm playing. The piano for me is that, it's like my everydayness, so I was always kind of avoiding it. That's how I managed to not really put it in any tracks for a while.”

For an album that’s all about giving in to what feels good, leaving out his beloved piano was not an option. “It's in the name, Hotel Surrender, which was really about checking into immediacy, to naturalness, to whatever is unfolding in front of you in the moment. And that meant playing the piano,” he smiles. “I used to always be like, oh that feels good, but I've got to find something that's abstract, like treasure in the unknown. But for this particular record, not just musically but philosophically, life-wise, what's in front of me is good enough. And that's it. That's the purpose. I didn't have to be on some massive quest all the time. Definitely one of the major new DNA points of this record was just like, letting go and surrendering.”

It’s a theme you can feel across the record as blissful and comforting soundscapes seamlessly slip into smooth and soulful jams. Murphy’s delivery is rich, full and joyfully commanding. His lyrics are hopeful and optimistic, balancing philosophical sentiment with knowing tropes. The production is crisp and capacious, full of warm, fluid basslines, dynamic percussion and driving energies. On “Get High” Murphy mixes synthetic loops with the organic playfulness of his piano playing. It’s laid back and relaxed, full of heart and style, carried by effortless hooks and his emotion-packed vocal, while on “Whatever Tomorrow” he twists and catches you with an imaginative soundtrack of artificial kicks, drops and thick gushing strings. “Whatever tomorrow, whatever that means. Whatever tomorrow, got the best of me,” he croons with an invested nonchalance. “Feel Good” is less a single and more a mission statement for the record. Thumping with melody, it’s propelled along with the low riding rush of harp flutters, eclipsing strings and a stiff backbone groove. Driving with pure motivational aspiration and shamelessly kitsch, it's bursting with funk, slick basslines and an intrinsically positive vibe.

The sentiment of Hotel Surrender may be upbeat and jubilant, but it has weight, something Murphy feels strongly about. “I don't think you can write happy music unless you've truly experienced unhappiness, because then it has this sickly, primary lack of depth. It's just it's like, yuck, it's like bad sugar,” he winces. “When you're young, you think positivity is lame. But that's because you're coming from a place of simplicity, so you're attracted to complexity. I’m generalising, but often I think people who have been through or are in a place of complexity, you understand the true glory of simplicity, of just how powerful it truly is and what a gift it is to just smile or dance or feel good. After close to ten-years of doing this, I've taken enough punches and criticism from the outside world. After a while you realise, no matter what you do, people are gonna have a problem with it. So like, I might as well do what feels good. You know, instead of trying to impress people, just impress yourself.”

After working as an artist for over a decade and taking in some phenomenal highs and some painful lows, Murphy has the perspective to find the value in moments which matter. “If you think of your happiest memories, they're always so simple and never complex,” he smiles. “I remember when the first Chet Faker thing happened, I played the Boiler Room, I played The Ellen DeGeneres Show. I think I played 125 shows that year, basically in a different country every three days for an entire year. And the two happiest moments of the whole year? It wasn't winning these huge accolades, it wasn't playing the most widely syndicated TV show on the planet Earth. One was having coffee in the morning, out in the sunshine, and another one was in Japan in this park on my own. I went for a walk, and I looked up, and it started snowing as I was looking at the sky. It was just so simple.”

It’s an outlook that’s brought a new energy to not only Murphy’s music, but to his way of living. “That’s what I've been trying to get at with music is using it as a kind of vessel towards simplicity and being. The point is not to over-complicate, it's actually to bring you to a place of simplicity and just being, and to check into Hotel Surrender. It’s a place in you, right now. The hotel is you, go surrender to reality. Whatever is happening is what's happening right now, and even if it's not good, you can feel better in that just by accepting it. I think most suffering people go through is not accepting reality as it is and thinking that it should be other, it should be another way, we always have some other way. It's good to have an idea of another way so we can work towards a better place.”

As developed countries begin to ease restrictions and life starts to feel more positive, Murphy believes he’s not alone in his new perspective. “Most people, I think, felt what happened and have realised life is short and fleeting,” he nods. “Yes, the world or life if we zoom out is troubled, but right now, this very space that I occupy is not. We don't need to ask permission to feel good. We just can, and that's okay.”

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Tunde Adebimpe

Thee Black Boltz

Julien Baker & TORRES

Send A Prayer My Way

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE