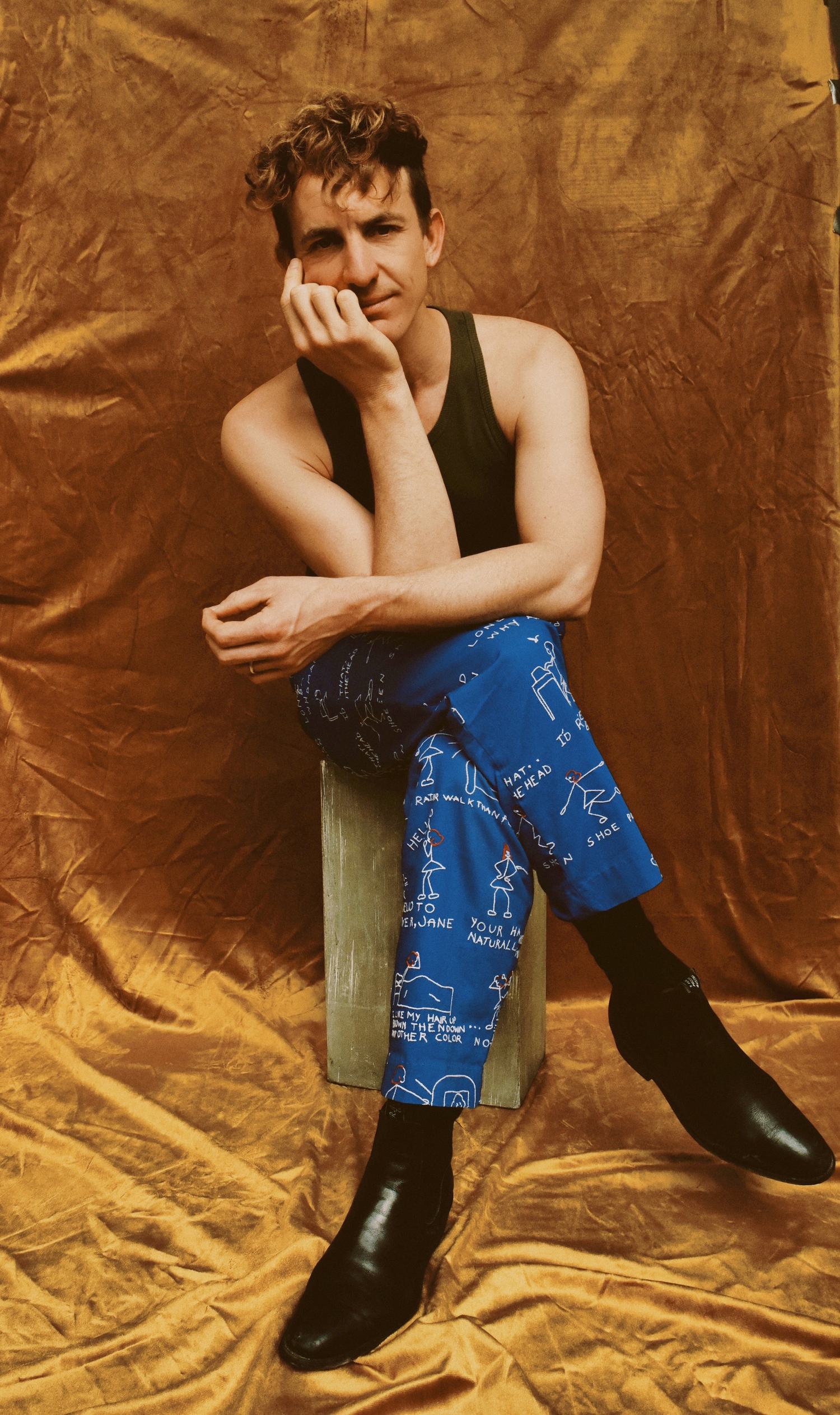

Love, honesty and Buck Meek

Love in all its forms takes centre stage on Buck Meek’s third album Haunted Mountain. He tells Rick Burin about finding new ways to explore music’s greatest theme.

“I’ve been trying to be more honest,” says Buck Meek. It’s a theme to which he’ll keep returning. And, though, when he does speak, he speaks fast, he’ll often respond to a deeper question by planting a fist against his temple, gazing off into the distance, and falling silent for close to half a minute. When he’s being that careful with his words, you realise it’s not because he’s worried he’ll tell you the truth, but because he’s worried he might fail to.

Honesty permeates Haunted Mountain, the 35-year-old Texan’s third solo record – and his first for 4AD – which is characterised by its spacious sound, a preoccupation with love of all kinds, and an earnestness that’s rare in rock and roll. Has that quality always been important to him?

“It’s definitely something that has taken time for me to nurture,” he says. “On my first EPs, and my self-titled LP, it was important for me to embody different writing styles. But with Two Saviors (2021), I started to attempt to be really honest. And that’s just been inspired watching people like Adrianne Lenker write – and Mat Davidson.” Lenker is, of course, Meek’s co-conspirator in Big Thief; Davidson plays pedal-steel in Buck’s band, and produced this new record.

The aim with Haunted Mountain was to apply the authenticity of Two Saviors to cheerier if no less exposing themes. “My second record was very confessional, but at a time of loss, so writing those songs was a healing process for me,” says Meek. “With this one, I wanted to continue to write very truthfully and from the heart, but honouring where I was at this point in my life, which is: in love, and in a pretty happy place. And I was trying to be honest about that in a way which felt really vulnerable, because there’s often taboo around happiness.”

Is he comfortable telling me about that experience of love, and how it influenced the record? “Yeah, for sure,” he says amiably. “Well… I… let me just think about this for a second…”

He falls quiet and leans his head against his fist, essaying the ceiling. He is sitting on the floor of his home in the Santa Monica mountains, wearing shorts and a polka-dot shirt, his tousled hair tumbling over his forehead. He nods finally, and his hair bounces. “About four years ago,” he says, “I fell in love with this woman in the Netherlands – who is now my wife, Germaine Dunes – and of course we were very far apart. We met each other once, then we wrote letters for a year, and then we would meet in different places around Europe. Whenever I finished a tour, I would bring my tent with me, and we would go to the mountains and camp, just for a week or two. And there would be a lot of time in between, where we would be writing. So a lot of the seeds for these songs came from that time in my life. That definitely encouraged me to write love songs.”

The straight-up loveliest song on the record, “Didn’t Know You Then”, had more complicated origins. His friend Luke Temple had challenged him, during a joint songwriting course, to write the most clichéd love song imaginable, by committing to whichever pre-prepared prompt he selected. “So I chose the cliché, ‘I’m nothing without you’, and my chorus went, ‘I’m nothing without you/With nothing to die for/My life is only waiting’. I wrote the most co-dependent chorus I could, with three cliches! I had written it as a joke – as an assignment for Luke – but then I sang it for my lady, and she blushed, and she loved it. It meant so much to her, and it also felt really good to sing. To sing something that was so heart-on-the-sleeve like that felt so cathartic.” With some tweaking, it was transformed from a meta joke into the template for the album. “I rewrote the chorus because those particular words felt dishonest to me – that didn’t feel genuine. But the sentiment of the first verse, and then the chorus that I landed on eventually: that was true. I tried to find the truth within the song for myself. And that was kind of the beginning of that side of the record.”

By ‘that side’, he means the headily romantic side, because while Haunted Mountain is an album about love, its remit is not restricted to romance. “I also wanted to write about other aspects of love: platonic love, and the love of a mother, and the love of a mountain,” says Meek. “And even with romantic love, I was trying also to talk about the reality of it, with songs like ‘Secret Side’: how we’ll never fully know another person as much as we think we do, and how a lot of conflict can come from that. I wanted to really talk honestly about challenges and what it means to be in a relationship. Which to me is one of the great values of being in love: when you actually get through that romantic phase and you get to the real stuff, you know?”

His songs have often taken the form of conversations between a couple. The listener drops in, sometimes partway through, to catch snatches of dialogue. “That’s a device I still use, and something that just feels very natural to me,” he says, “but on this record I was putting a lot of thought into creating an environment for those fragments of conversation. I was trying to support all the senses so the listener could inhabit the songs: providing the light, and the time of day, and the time of year; a sense of place; even materials – to create an environment to live inside of. It’s something that a lot of my favourite songwriters do, and so I’ve always tried to find my own way into that.”

Often, on this album, that environment is the mountains. I naively expect Meek to say that he lives there because it’s peaceful, or tranquil. Instead, he says that he is “definitely drawn to the danger and the volatility of the mountains. There’s a lot of mudslides and fires and, you know, all kinds of wild things you have to stay aware of, where I live at least.”

That fusion of nature and chaos is present on Haunted Mountain’s song, “Cyclades”, which begins with his father nearly crashing a motorcycle into an elk. There is a wholesome surrealism to Meek’s life of which he appears only partly aware. At Big Thief’s recent Edinburgh show, he took a break from the ambient sounds and anti-solos to regale the crowd with a story from his childhood about searching for doubloons in a Scottish castle. “That doubloon story is true,” he says, “and the story that starts ‘Cyclades’ is also true, but in the third verse I admit that I mythologised another one and exaggerated it in my child’s mind, to the point where it was not.”

That tale involved his parents defying the laws of physics as they literally passed through a truck. “I suppose it’s a joke about how the line between mythology and history is very thin,” he says. “But I could swear they told me that story growing up. And what’s weird is that my little brother, Dylan, remembers them saying the same thing!” Meek grins. “Which leads me to believe that maybe it did and they forgot… you know, it’s one of those things like Peter Pan…” Where only children can understand that this happened? “Yeah!”

Five of the songs were co-written with folk singer Jolie Holland. “She has the deepest understanding of real American music of anybody I’ve ever met,” says Meek. “American folk music is embedded in her body.” He says she approaches songwriting from a place of prose, while his role is to counterbalance her “super-beautiful” lines with “simple human concepts”. “When I brought her the song ‘Lullabies’, about the love of a mother and son, and birth, and the letting go of a child, her contribution was this old midwifery ritual where the midwife arrives to the place of birth and unties all of the curtains in the room and all the braids of the women in the room, to make space.”

That feeling of space is integral to Haunted Mountain. Whereas Two Saviors was recorded in a cramped room in New Orleans, for the new record the band decamped to the airy Sonic Ranch studio in the border town of Tornillo, Texas. When Davidson stepped up to produce, one of his credos was to, in Meek’s words, “create as much space as we could in the arrangements and the playing, in the tempo and in the space between the notes”. While “Undae Dunes” remains melodically dense, songs like “Paradise”, “Lullabies”, “Mood Ring” and “Lagrimas” reflect the new approach: “more space and more sensitivity,” as Meek puts it.

“Lagrimas” was a song that “kind of wrote itself”, Meek says. Holland sent him the first verse – rife with ritual – about hiring a necromancer to communicate with a loved one who has died or disappeared, and he finished the song. “I was going through the loss of my grandmother at that time,” he says. “She was like a second mother to me, and passed away very suddenly this year. And so I think I was writing that song in the grieving process. Even though obviously it’s a fantasy, it felt very true.”

There are many ways to commune with the dead. The album’s closing track, “The Rainbow”, is a collaboration with Judee Sill, the Californian singer/songwriter who died of an overdose in 1979, aged just 35. Meek was asked by the makers of a new documentary, Lost Angel: The Genius of Judee Sill, if he was interested in putting one of her incomplete songs to music. “She had a lot of unfinished and unrecorded songs in her journals,” he explains, “some with sheet music, some without. And the very last entry was this unfinished song written for her ex-boyfriend Lyle and his daughter Heidi, and dated just a few weeks before she passed away. There was no song form yet – it was just these different iterations of the verses, with some rhyme-schemes worked out – but the core was there. So I took the words, which I had to rearrange a bit, and then put a melody and a harmony to them, and I titled it ‘The Rainbow’.”

Meek was already a fan of Sill’s work. What first drew him to her? “I’ve always loved her understanding of subtle emotion in melody and harmony,” he says, of the artist who once told the NME her principal influences were Bach, Pythagoras and Ray Charles. “The basic idea in music,” says Meek, “would be, ‘a major chord is happy and a minor chord is sad’ but then with complex harmony, you can access more complex emotions.” For my benefit, he races through a beginner’s-guide to complex harmony, from major sevenths (“bittersweet”) and flat sevenths (“sultry”), to minor sevenths (“sombre and sweet but kind of sad”) and diminished chords (“dissonant and chaotic”). “And the more you add to the harmony of the chord, with ninths and 11ths and 13ths, the more subtle the emotions become – there are so many variations of this harmony. Judee Sill is someone who applies that directly to her lyrics: if she’s talking about something bittersweet, she will use a major seventh chord. And that’s rare to hear in a songwriter. I’d always assumed that was intentional, and it’s something I’ve tried to do for a long time, partly inspired by her. But what was amazing is: when I had her journal, there was a whole page where she had actually listed every interval and assigned complex emotions to them. It was a map! That was pretty wild to see. And I used that in writing her melody – the melody for her song, ‘The Rainbow’.” How did it feel to be the conduit for her last song? “I definitely had to really take a breath and embody it,” he says, “just to not feel unworthy.”

So far, so unstintingly honest. It turns out, in fact, that the only thing Meek isn’t prepared to discuss is Bob Dylan. Buck was hand-picked to be part of Bob’s on-screen band for the lockdown-era Shadow Kingdom project, and I’m interested to know what he took from that. He instantly straight-bats the question, in the vernacular of his former boss, accompanied by a crooked grin. “Well, I wish I could talk about it, but I swore to a very intimidating cowboy that I would not speak a word of the experience. I’m forbidden!”

"Honesty can be brutal, but it’s always the right way.”

Instead, we move onto Big Thief. Buck balances his solo work with his role as one of the four irreplaceable components in the world’s greatest country-indie-folk-metal band. What position do those two different projects have in his life? What does each give him?

“With Big Thief, I’m blessed to have the freedom to shape-shift,” he says, which is a very Big Thief thing to say. “I’ve been playing guitar since I was five years old; I didn’t really start writing songs until I was in high school. So the guitar is even deeper in my blood. With Big Thief, it’s so free, I can embody a completely ambient space. I can kind of disappear and just create whale sounds for a while, or I can go into a very outward place on the guitar. I’ve always contributed to some degree in the songwriting sphere, but it’s mostly just supportive, with songs like ‘Certainty’ and ‘Two Hands’. Big Thief allows me to be part of a collective. It feels like we’re more than the sum of our parts: we’re like one body, and we lose ourselves in the band.”

Leading his own group is essentially the opposite. “There’s this responsibility for me to be the guide for my band, and also for the listener, taking them through a story or an experience. It’s an honour, and very empowering, but also exhausting. I personally need the balance of being able to go back and forth between that and Big Thief, where I can just dissolve into this collective.”

Big Thief’s last album betrayed a strong country influence, while their live shows in the past two years have escalated into metal. Where will the band take us next? “Well, we’re building our own little recording studio right now,” says Meek, “and I’m heading over in the next few days to crack into that. I think we all unanimously want to try to write the heaviest music we can; to write what rock and roll means to us, in the heaviest possible way. That’s our starting point.”

Meek and Lenker were married once, then divorced, but they remain “deep friends”, in her perfect words, and continue to make beautiful music together. I used them as a template, I say, when I went through much the same thing. It meant a lot to us to see their example. I hadn’t intended to tell him that, but all this talk of honesty made me want to. “Hell yeah,” he murmurs, when I’ve finished offloading on him. “Thanks for saying that… The music definitely is what helped us transform… that accountability of taking care of the music, I think… having a thing outside of ourselves to move through the transition.”

Their relationship is clearly incredibly special, I say. How has it influenced him as a person? The pause this time is the longest of the interview. He wants to say it right. “Well, in so many ways,” he says eventually, “but… the first that comes to mind is that she is one of the most honest people I’ve ever met. She’s always been a North Star for me in regards to truth – in her relations and also in her songwriting, and in the way she approaches music – and that’s been huge for me. I’ve always looked up to her in that way.”

He considers this for a moment.“You know, honesty can be brutal, but it’s always the right way.”

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE

Mamalarky

Hex Key

Florist

Jellywish