Breaking character

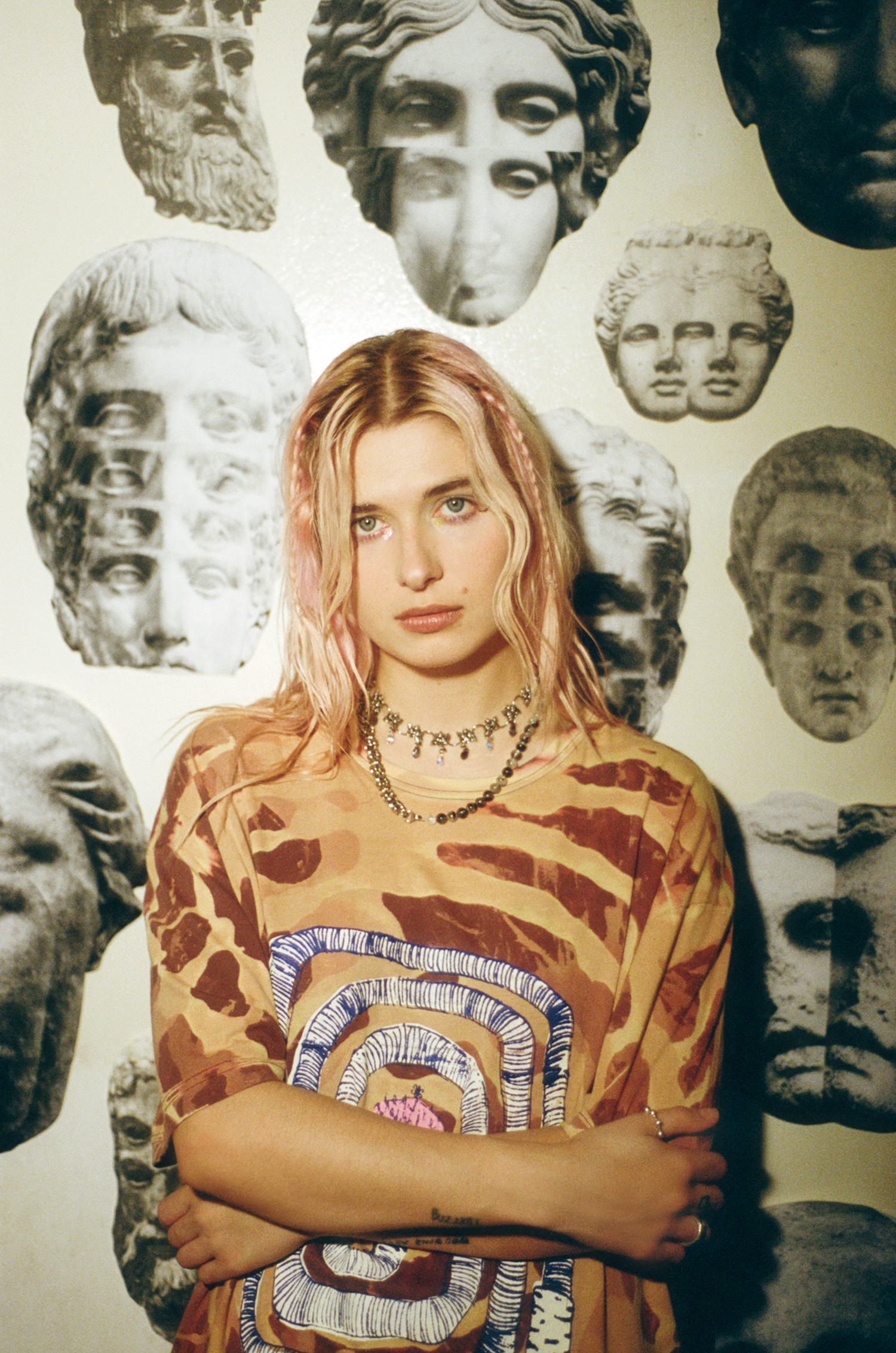

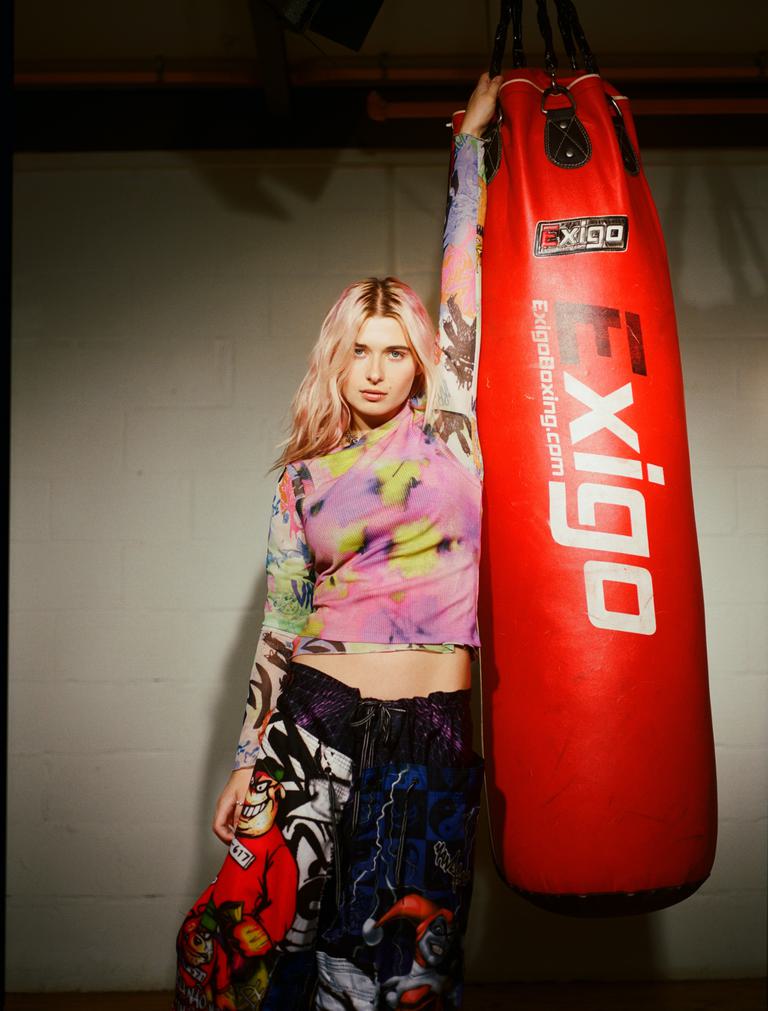

Styling by Amy Stephenson with assistance from Bryony Wardle \ Hair by Chad Maxwell | Makeup by Lucy Wearing

Lead image: Sweater by Sarah Garfield | Jeans by GERM | Jewellery by Closet Children

After years of using Baby Queen as a front to both protect and propel her own hopes and experiences, Arabella Latham is ready to break out and embrace the popstar she was born to be.

“It’s a traumatising experience,” laughs Arabella Latham with despair. We’re digging into her demons one song at a time as we discuss her debut album Quarter Life Crisis. “I just keep saying to people, I don’t know how people do this, make albums. If you really care about it, how do you know?”

Since moving to London at the age of eighteen, Latham has tested countless paths to breaking into the music industry, from knocking on label doors to taking a job at Rough Trade East. Despite losing her way at times, she funnelled her pain into perseverance and doubled down on her dream.

She built Baby Queen as a character, a magnetic pessimist with nihilistic tendencies who’s always the life and soul of any party. But it was also a way to fake confidence and create a protective barrier that kept the world at bay. As Latham matured, so did her writing, and it became more difficult to keep the two exclusive. “I think Baby Queen is what I always wanted to be and slowly but surely I’m being able to step into that person and that’s amazing,” she says. “The lines do get blurred and it’s very confusing sometimes.”

Balancing the need for authenticity with the character she’s constructed is a fine art that’s played out on Quarter Life Crisis. From the opening monologue of “We Can Be Anything” to the aching lament of “Obvious,” Latham pulls from her past, her multiple streaks of identity, and softens with hope. “I feel like this music, there are some really snarky, satirical songs on this album but I think moving forwards it’s going to be really interesting to uncover who Baby Queen is as I grow up and am less bratty,” she laughs.

Originally from Durban, Latham grew up surrounded by music. On her mum’s side, her great-uncle was Graeme Beggs, an esteemed music producer in South Africa who held the market’s rights to ABBA and formed the band Clout. Her dad was a huge music fan and would make genre-specific mixtapes as a hobby. “I remember this one, Sonic Seven, was his journey through psychedelic rock. We had a limbo lounge at our house and he would DJ all the time,” she smiles.

While things might have been richly musical in the limbo lounge, Latham found the scene around her to be quite limiting. “It’s very hard to make music in South Africa that has a global reach,” she explains. “I was very lucky growing up, but it is quite reserved and everyone behaves in the same way. I guess I felt slightly trapped in that I couldn’t express these extreme parts of myself that were there. I didn’t have a vehicle for it because I couldn’t stray from the confines of what you’re taught that you should be.”

She persevered and begged her parents for a guitar. At home, there was an old piano which her sister used to practise on. Between the two instruments, Latham began to experiment with songwriting. “I hated music lessons, it’s all very classical and it’s just not the kind of music that I was interested in. But I started at about the age of ten to just make stuff up,” she explains. “I really enjoyed making stuff up and making up my own melodies. The only piano or guitar parts I ever knew were things I had created. I didn’t have the attention span to sit and learn anything.”

She began releasing music under her own name. “It was just so lame,” she laughs. She made demos at home using a USB microphone and the recording software Mixcraft 2.0. Coming home from school everyday, she’d write songs like diary entries. “My friend at school would fancy Harry Styles and I’d write a song about how she wanted to be with Harry Styles. I’d just write songs about everything,” she continues.

Championed by her dad, he encouraged her to make a demo CD with one of his friends who was a producer, eventually setting her up with a manager. “It wasn’t real,” she says. “I was making my own demo CDs and printing out an image of myself. It was very silly, but I did get a couple of songs played on the radio out there and I did play a few gigs opening up a stage at a festival near a shopping centre or something stupid.”

Despite her best efforts, Latham felt as though there was only so far she could get in South Africa. With her sights set on the UK, she began to make plans with meticulous determination. “I was making excel spreadsheets of every single record label, every single magazine,” she says. “The Line of Best Fit was definitely on the list. It was all the email addresses of all the writers and editors. I probably sent an email to you guys and you were like, block.”

Growing up, Latham was a huge Swiftie, the influence of Taylor still present in her music today. Having such a fearless role model helped generate the self-belief that her dreams were realistic. “Watching Taylor, there’s no one better to learn from. It’s also completely unrealistic,” she counters with a cackle. “I think I was just very delusional and very ambitious. I think when you grow up somewhere like South Africa, you’re so far removed that it can become this huge thing that you build up in your head. It’s so difficult and so impossible that you almost feel like you’re preparing for war. I felt like I was preparing for war, leaving South Africa.”

Making the trip over with her parents’ blessing, she moved in with her aunt and cousins in Fulham. Armed with a stack of demos, she spent her days trekking across London, doorstepping the city’s record labels. I ask how long she persevered with her mission? “About a week,” she replies with a burst of laughter. “It was very quickly apparent that I needed to really reassess everything. It’s just a very isolating experience. Nobody wants to listen to you, nobody cares, and I think I realised that in order to get people to take me seriously I needed to create something that was unique and I had to get a lot better.”

It also became quickly apparent that she needed to find somewhere to live. “I couldn’t keep staying on my family’s floor and in all my cousin’s beds. One by one they’d get sick of me,” she says. “Eventually I moved out and I moved into a friend’s dad’s empty apartment with them and I would sleep on the floor. Then I slept on a few couches, then I started dating someone and lived on a river boat on Regent’s canal.”

It was that relationship which turned out to be something of a catalyst for Latham. “I got dumped in Clissold Park and when I got dumped in Clissold Park I threw up on the side of the road and I said, in my head, ‘Fuck you bitch, I’m going to become the biggest musician in the world,’” she groans. “I fell in love and it was a very, almost psychologically abusive relationship. Looking back on it, it beat me down a lot and I think I got quite distracted from the one reason that I came here.”

Latham started playing in bands and expanding her social circle, putting herself in positions that felt like they were elevating but required little personal risk. “I think I was very much on the periphery and trying to call myself a musician,” she explains. “I started making friends with influencers. I think that I just got swept into this world of vapidness and of feeling important because I was standing next to someone that was slightly important instead of focusing on creating something significant myself. I was just sort of floundering around these other people and these other scenes for a long time.”

"You can write a song in a million different ways, but Baby Queen has to fit within these parameters for it to feel like it’s a Baby Queen song."

Balancing a day job with songwriting, she went through a series of bad management partnerships, further eroding her self-belief. “There’s so many managers that call themselves managers but they’re just men,” she says, shaking her head. “They do not have the vernacular to be able to call themselves a manager. They’re just a man that attaches themselves to a bit of talent.”

However, the first man she worked with did get one thing right - introducing her to producer King Ed with whom she continues to work closely. While her influencer networking may seem vapid with the benefit of hindsight, it did lead Polydor to discover her on Instagram. When they emailed asking to hear music, Latham was ready. “At that point I’d been in with King Ed three times a week for two years, just making this music,” she smiles. “After that, it just happened.”

Speaking to Best Fit about those early years, King Ed tells me, “I think there’s a magic in that period before an artist releases anything, before it becomes something real. From day one I was convinced Bella was an important artist. She was quieter when I met her, less assured of her own talents, but they were obvious to anyone who was listening. We got together and wrote a song about a car or something (!) and her lyrics off the cuff were brilliant. No run-of-the-mill rhymes, nothing trite, just clever, witty, fascinating turns of phrase.”

When Latham signed with Polydor, she was brand new in the eyes of the industry. With nothing yet online, the label decided to build her from the ground up and immediately began to release music. From her debut single “Internet Religion” released at the height of the 2020 pandemic, she began dropping a track nearly every six weeks. “I released a lot of music and I think that might be one of my regrets looking back, of how much music came out,” she says. “But I guess if you’re starting from nothing, you don’t have any sort of platform to use, you have to just fucking hit it. It was very intense.”

Despite slowly building a reputation for her precocious pop cuts, it was her alignment with Netflix’s Heartstopper which really propelled Baby Queen into the spotlight. It was released in spring of last year and became an instant hit, making overnight stars of all those involved. “We were releasing music for a while, but I think when Heartstopper came out it did feel like, this is a starting point,” she says. “Like, we’ve done all this work before but it felt like that was the moment where people really started to pay attention. It’s been a long road.”

Based on the graphic novels of Alice Oseman, the series depicts a blooming relationship between two school boys and the intricacies, struggles and personal journeys involved. Delicate, intimate and empowering in its warmth, the culture which now surrounds the show has become bigger than the sum of its parts. Baby Queen’s music appears throughout both series, six tracks in total. She penned the song “Colours Of You” exclusively for the first, while for season two she wrote “All The Things.” By her own admission, Baby Queen is synonymous withHeartstopper.

Speaking to Best Fit about her involvement in the show, Executive Producer Patrick Walters tells me, “We’re so lucky to have Baby Queen’s music feature so prominently in Heartstopper. She has more music across the first two seasons than any other artist. The energy and hooks in her songs, married with the potency and longing in her lyrics are a perfect soundtrack for the show. No other contemporary artist combines youthful existentialism with such wit and impact.”

Trying to reconcile her engagement with the identity of the show alongside what she’s built as Baby Queen has at times been a challenge for Latham. “The marriage of Heartstopper, it just felt so natural and it just felt so organic. I felt so accepted into that world,” she says. “I want to be defined by myself and I think that’s been a really important thing for me. Now that the second season has come out and I am more involved, I don’t want it to overshadow the record. I’m just trying to let them live side by side.”

Despite the jostling of worlds, her inclusion in the show’s community has been both inspiring and encouraging. “I think when the whole Heartstopper thing started happening it was just a feeling like you had whiplash. I think for a month afterwards, no one knew what was going on. It was the craziest reaction. When the second season came out in August, you can go onto Spotify for Artists and if you go onto my streaming statistics it’s like…” she motions her hand across a flat line before shooting it into the air. “Then it just goes way up! It’s really fascinating just how wide that reach is.”

So close are the two, Latham even took a cameo in the recent series despite knowing it would drop around the same time she began to share tracks from Quarter Life Crisis. “I was desperate to be on that show. I was like, ‘Alice, please. Let me in, please.’ I really wanted to do it,” she laughs. “We had some conversations about not looking like Baby Queen in the show. We wanted to look like the singer in the school band. We were just trying to separate those slightly.”

Latham's battle with the identity of Baby Queen is forever shifting. The process of creating Quarter Life Crisis happened over three years. Her previous songs had taken a grungier direction but as she changed and as her career progressed, so did the music she was working on. “I went from making one completely different album to the album that we have now. None of those songs that were on the first draft album have even made it on,” she says. “It’s very hard to preempt the art before it exists. I’ve never held songs back from anything. I’m always, ‘Put the best stuff out and I’ll make better stuff.’ That’s always been my thing.”

While her policy made sense in theory, in practice things weren’t quite as easy. Deep into the album process, Latham struggled to find any sense of objectivity. Piecing together the tracklisting and sticking with her decisions as the puzzle shifted proved an impossible project. “I’ll often go back to an idea from years ago and rework it thousands of times. It was just chipping away and then you make one song that changes the whole vibe, then you have to kick out these two songs because they’re wrong. Then you can suddenly pull this one back in because all of a sudden it makes sense,” she grimaces. “It was traumatic. An impossible, impossible, impossible, impossible process. Worst time of my life, actually.”

There came a moment in her journey where Latham had to surrender. No longer able to differentiate between demo, final mix and master, she stepped back. “It’s a nightmare. I don’t know how anyone else will ever describe it as a beautiful cathartic experience because I was like a walking ghost for months. People would speak to me and it was just like chewing the inside of my lip, my leg constantly going like this,” she frowns, her knee bouncing nervously. “Just traumatised.”

A lot of the pressure that Latham put on herself came from her respect for the tradition of the album and her desire to follow it. “I’ve always wanted to be an album artist and an artist that releases albums,” she says. “My favourite musicians, I think of their records and those albums define periods of time in my life. An album is this very sacred thing to me, so I think it was a lot of pressure from myself, but also it’s just so much pressure because I don’t want to fail. I don’t want to flop. I want to fucking do it. I want it to be the best, so good isn’t good enough. It has to be great. It has to be incredible.”

Speaking to Best Fit about the album recording process, King Ed says, “I really felt for her! This album, of course, matters an enormous amount to me, and is probably the thing I’m most proud of to date, but she’s going to make great records as long as she wants to be writing them.”

While a lot of the songs were sketched out across a period of three years, the real bulk of the album was put together across an intense three month sprint. Latham remembers spending both Christmas Day and New Year’s Eve writing, flipping her body clock to work through the night and avoid distraction. “I just find the nighttime to be a bit more of a silent creative, artistic, inspiring time,” she says. “If you have a meeting at 4pm, I can’t do any songwriting before that. I feel like you have to be completely freed of everything else.”

Quarter Life Crisis is a surprising listen. While the precocious presence of Baby Queen still echoes through the tracklisting, her delivery feels softer and her sentiment is more vulnerable and open. The choruses shine while the verses are lyric-heavy tapestries of narrative that turn and ebb with playful spontaneity. There are hints of The 1975’s pessimism, Wolf Alice’s soft-sung whispers and even a little dusting of Swift’s ingenuity. It feels like a coming of age, and perhaps that’s part of the panic. Change is rarely easy to embrace but difficult to avoid.

Album opener “We Can Be Anything” hits a diaristic stream-of-consciousness rhythm. Its lyrics witty, self-deprecating and illustrative, it offers a surprising note of hope. “Anything that’s like a minor chord or even sounds gloomy, I just don’t like it. My ear doesn’t like it,” says Latham. “I really like euphoric, big happy sounding things. I just like those sounds. ‘We Can Be Anything’ is a very interesting song and it is more positive than some of my other work. I actually think I just got to this point, and especially as you’re growing up, it’s like how long can you keep being this satirical? How long can you keep that going for?”

When Latham created the character of Baby Queen she was looking for a way to be bigger, brasher and fearless. However, as she’s grown and gained confidence, the true kind that embraces vulnerability, her creation has begun to feel restrictive. “Sometimes I feel like I’ve created something that I suddenly have no control over. You can write a song in a million different ways, but Baby Queen has to fit within these parameters for it to feel like it’s a Baby Queen song,” she says. “I think that’s been kind of difficult because there’s songs on the record that have completely left those parameters, entirely.”

Another indicator of Latham\s growth is in her wordplay and the cadence with which she delivers some inspired lyrics. Lines like, “I said, ‘Hey don’t be so defeatist,’ she said, ‘Well don’t be so naive it’s been proven space is exponential so this is all inconsequential,’” are so quick they demand revisiting. “Sometimes I feel like making music is like maths. It’s all about the syllables of the words, but also you can have the right syllables but sometimes the words don’t bend into each other in the right way because one’s ending on the wrong consonant, one’s starting on the wrong vowel, and it’s about the way it flows off your tongue. That’s what I love about rap music. The really great rap music with great lyrics, it’s absolutely phenomenal. The rhythm of those words. My second album is going to be a trap album,” she laughs.

Even if the boundaries between Latham and Baby Queen are beginning to blur, she still credits her invention with having “literally saved my fucking life.” She created her as a mask, a means to be bolder without the constraints of accountability. “I think I’ve gotten a lot more confident and comfortable with myself now. But the person that I am, I’m deeply insecure, deeply afraid, deeply ashamed of who I was and I think terrified to express myself in the way that I felt I truly wanted to,” she explains. “I think if you name yourself Baby Queen, you can be like, ‘Oh that’s not me, that’s Baby Queen,’ and it gives you the bravery to push it further and to do things that you maybe wouldn’t do if your own name was attached to it.”

"Payback via success – it’s been a driving mechanism for me. Not anymore, so I have to find new ways to be engaged."

Speaking about Latham\s work in character, King Ed says, “I always think she’s aware of the character she’s embodying in the song. Like Lana or Gaga she can play up to this to make it hit a little deeper or twist the knife somehow. I think it’s this strength of character that defines her music. Her songs couldn’t be sung by anyone else.”

One of the ways in which Baby Queen has helped Latham is in realising and vocalising her own sexuality. On “Dream Girl,” an unrequited love letter, she writes with equal measure of hope and fantasy to the object of her affections. In 2023’s pop climate it feels subtle, but for Latham the open use of such deterministic pronouns marked a big step. “It was something that I was deeply, deeply ashamed of. I’ve accepted myself. I’ve actually accepted myself and I actually am proud of who I am so why the fuck should I lie about it or hide it anymore? Because I think that once you finally accept yourself, it’s very difficult not to live your truth.”

Part of the confidence she found to be open about her bisexuality came from the Heartstopper community, the show itself illustrating the personal nuances of every coming out story. “I was never not open about my sexuality, I just maybe preferred to stay away from the topic,” she explains. “I think with Heartstopper it just created a bigger group of people that are embracing you and validating your feelings. It’s just this love for something about myself that I’d never experienced before and all of a sudden it was fine. It’s not that big of a deal anymore.”

Quarter Life Crisis feels like a personal journey. Just as some tracks are confrontational, others offer vulnerability. A song like “i can’t get my shit together” bounces from self-depreciation to hedonistic celebration in an explosion of hyper-pop while a track like “Obvious” confronts consequence with tenderness and a hint of Swift’s introspective and melodic influence. “I think that you can almost group the album thematically,” she says. “I was very conscious of not wanting to repeat myself, not wanting to say the same thing twice. Where ‘Grow Up’ is tackling my inability to grow up and all the childish things about me, a song like ‘Obvious’ is actually tackling what I’ve left behind. They’re different facets of a similar experience. ‘Dream Girl’ was like stepping into the truth that I’m unable to step into in ‘23.’”

Title track “Quarter Life Crisis” is a pop-rock statement that reconciles the mixed emotions of looking forward and letting go. The heart of the album, it draws together the thematic strands that battle across its eleven other tracks. Broadening her creative process, Latham worked on the song with esteemed songwriter (and former indie sleaze heartthrob) Max Wolfgang. “I’ve only ever trusted Ed with my music and I don’t allow people to do lyrics, because I think that that’s where your artistry can become watered down and diluted. It’s really important to me that all the thoughts and the words are coming from my brain,” she explains. “Max Wolfgang is an incredible musician. I would write all the words and the lines and then Max would be like, ‘That should be the first line, that should be the last line.’ Then you’ve got that objectivity, in a way, when you’re working with someone where they can actually be like, ‘That is a really strong closer and that’s a strong opener.’ I learnt a lot from him.”

By breaking down the walls between herself and Baby Queen, Latham hopes she can find stronger connections in real life too. “I do feel really lonely in life. I think we all crave being fully understood. I think that more and more I’ve actually retracted from people and I’ve got a very small group of close friends,” she says. “I don’t have the luxury of being able to not have this be my whole world. It’s kinda sad. I think I’ve also just got really unhealthy relationship standards. I choose people that don’t want me back.”

Just as time is a healer, success is also the best revenge. The birth of Baby Queen may have come from a moment of darkness, but she sparked a fire in Latham. “That break up in Clissold Park, it really hit me hard,” she says. “There’s so much of that in how I managed to give myself the impetus to get shit done. So much of it was fuck you, to so many people. Payback via success – it’s been a driving mechanism for me. Not anymore, so I have to find new ways to be engaged.”

With the release of Quarter Life Crisis, Baby Queen is growing up.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex