Alice Boman and the Self-Care of Simplicity

On her second album, Alice Boman remains a gentle, dream-like presence. She meets Alan Pedder in Malmö to talk about how new love and old routines informed The Space Between

Caught between the twilight of her searching and the dawn of long-desired love, Alice Boman finds reassurance in repeating herself.

On her second album The Space Between, the Swedish singer/songwriter continues to inhabit a distinctly interior world. There’s no weather to her songs. No social context. No third-party pressures. Only the appealing of one heart to another. But where her long-in-the-works debut Dream On was largely immersed in the mechanics of drifting and falling apart, here her gaze is pointed in the opposite direction.

Such a shift might have acted as a swerving point in her music, but on reaching every crossroads she seems to have just kept going. This is not a bad thing, just an observation; in the house that Boman built, The Space Between is less of a remodel than it is an artful rearranging of the furniture.

That wasn’t always the plan, mind you. Boman says she and returning producer Patrik Berger originally had ideas of making a much grander sounding record, complete with bells and whistles that her debut could only have dreamed of. But a casual recording session in Stockholm with drummer Nils Törnqvist hit upon something they didn’t yet know that they wanted: essentially more of the same, only closer, better.

I meet Boman in the late afternoon, in the courtyard garden of an art museum, a shaded oasis hidden from the outside by a tall wooden fence. It’s mid-August, the week of the city festival, and the squares are lined with street food vans and stages. People are out in their thousands, just not here; besides the two young women working in the café, there’s no one else around.

Tomorrow, Boman will play some of her new songs for the first time, in front of a hometown audience, with her regular backing band and Swedish labelmates Hey Elbow. Though she now lives in Stockholm, Boman was raised in the suburb of Limhamn, a short bike ride from the sea, southwest of where we sit now.

Although Malmö was becoming more and more multicultural throughout the ‘90s, taking in refugees from the war in Yugoslavia and, later, the war in Kosovo, Boman describes her childhood in the suburbs as like being in a bubble. “When I was growing up, it was super white, super middle class,” she says. “It was a very calm place, and good in a way, but it was more interesting in central Malmö where you could find people from all cultures.”

Boman was 12 years old when the bridge across the Öresund opened in the summer of 2000, transforming the city forever. She describes how she and her mother and brother cycled across to Denmark and back on the day of the inauguration. “There were no cars that day, it was just for people walking or cycling. I thought it was so cool to be able to do that.”

“These days, Copenhagen has become such a big part of living in Malmö, and it’s something I miss about living here. It makes Malmö feel so much bigger. I guess they wouldn’t say it was a twin city, but everyone here says it.”

At home, music was an important part of everyday life. Her father played guitar and was in a few cover bands, playing rock and country hits at weddings and parties, and had a regular gig at a pub in town. From the age of ten, Boman attended music school where she says choir was a big part of the schedule. “We would mostly sing old Swedish folk songs, but I used to look forward to December when we’d start rehearsing and singing Christmas carols. I loved that part.”

As a child, she would often come to our meeting place at the art museum, especially with her dad. She recalls one exhibition where the artist had painted a big black circle on the floor that looked as if it was a hole. “I remember being scared to fall into it, it looked so real,” she says, eyes widening at the memory. “I was not that old at the time, but I remember the feeling. I think they had a fence around it, or maybe they didn’t and that’s why I was so afraid.”

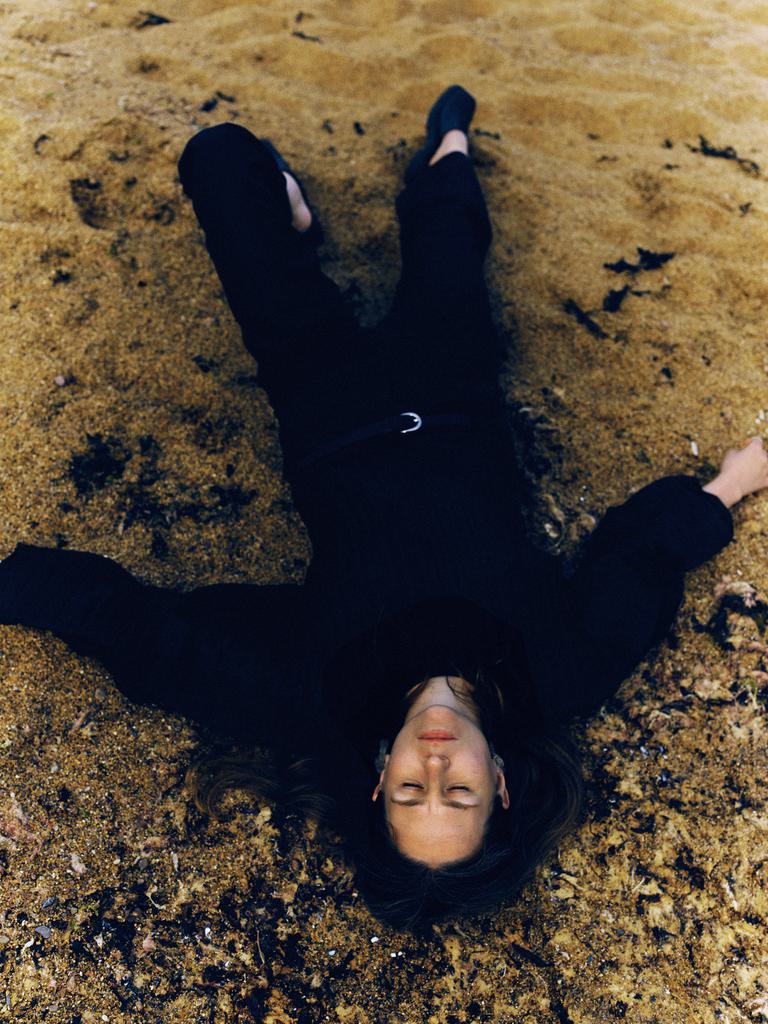

Viewing Boman only through her lyrics and her soft, zephyr-like singing, it’s easy to imagine that she’s governed by timidity. But while her songs tend to zero in on uncertain situations, in person she cuts a more forceful figure. Dressed all in black, her pale face outlined by her long brown hair and two large silver hoop earrings, there’s a gravity about her that doesn’t always come across in the ambient, spacious cocoon of her music. It’s in her absolute sincerity, and in the way she holds a gaze.

Any reticence she might have had in the first five minutes of our chat is gone in an instant when she breaks off mid-sentence and furrows her brow. “I… I think they’re playing my song,” she says, looking slightly alarmed. “That’s weird!” Assuming it’s coming from one of the stages outside, we try to brush it off and carry on. But so does the music, for the whole 45 minutes. One Alice Boman song after another.

Too distracted, we head inside to try and avoid it, but it turns out that the music is actually coming from the café. Clearly, she's been spotted and one of the staff is a fan. Boman lets out an exasperated laugh as we go back to our table. “I guess I’ll just do the interview like this,” she says, covering her left ear with one hand. “It feels like it’s echoing all over the courtyard.”

Back to the interview, and I was surprised to discover that some of Boman’s earliest recordings were partly written while she was studying ceramics at a school on Öland, the long skinny island I live on, several hours drive to the east. Fresh out of high school, she says she bought “an ugly little melodica,” packed her acoustic guitar, and went to train to be a potter. Writing songs was something private, she says, something she kept out of sight of her fellow students. “I was studying at a place that had a huge gymnastics hall with a piano and I would go there in the evenings and play when no one else was around.”

Later, when she moved to Öland to continue her studies, she started to fill notebooks with lyric scraps and song ideas that would end up informing her first home demos. “It was so calm, being there,” she says. “Maybe it was just because I had time to think, but something changed in me. So when I moved back to Malmö, I bought a handy recorder and started to make some sketches.”

Famously, Boman’s early drafts, recorded alone in her apartment, found their way into the hands of Malmö-based Adrian Records, who released them as they were in the summer of 2013. Within two years, the lead track “Waiting” was a word-of-mouth hit, amplified hugely by repeated use in the groundbreaking US TV show Transparent and a first-rate remix by fellow Malmö artist PAL.

The staggeringly effective simplicity of “Waiting” is something Boman has stuck to closely over the years. Lyrically, she continues to write as though she’s churning butter by hand, gently agitating her ingredients into the form she requires, turning the same phrases over and over. If anything, The Space Between is even more repetitive than Dream On – at least when it comes to the words.

“I like it when lyrics are quite direct,” she says. “There’s something about the simplicity of it that I really love. It makes it easier for people to attach their own meanings to a song, which is something I appreciate a lot when I listen to music. Songs that don’t force the words too much. Of course, I love Bob Dylan too, and other artists whose songs are like short stories, but in my own music I like it when the words are almost like a mantra.”

"Vulnerability is not something that I strive for, but I feel like it’s not something to try to avoid either. What comes out, comes out."

Boman may be economical with what she wants to say in her songs, but when it comes to space she’s full of generosity. In Patrik Berger, she’s found a musical partner who shares her love of leaving room enough in the production for each individual part to be heard. The combination is what gives her songs their startling clarity, which she implies is as much for her benefit as for ours.

“Songwriting has always been my way of making things become so much clearer,” she says. “Sometimes there is just too much going on and you don’t even know what you’re thinking. But when you sit down and start writing, you can see what’s actually happening.”

Or should that be what’s actually happened? Boman says she tends to write from the rearview. “I need to get some emotional distance from something before I can write about it, otherwise I am too in my feelings and it can get a bit hysterical,” she says. “A lot of people say it’s much easier to write when you’re unhappy, and that’s true. But it’s also true that it’s much harder to write when you’re really unhappy. I find it’s good to step back.”

Self-imposed margins are a hard thing to get right, and there were moments on Dream On where Boman seemed unsure of exactly how close she wanted to get to the source of her emotions. On The Space Between, the ambiguity of distance is entirely the point. But by virtue of being recorded mostly live in the studio, Boman navigates her emotional chasms from the same intimate baseline. It’s a subtle distinction, but one that makes The Space Between a more consistent listen.

When it came to the recording, Boman says that she and Berger had originally planned to rent a studio for two weeks, somewhere out in nature where they could be without distractions. Instead, with everything they needed already in Stockholm, they decided to just pretend to go away, while staying in the city. “I actually booked a hotel room, close to the studio, even though I live not too far away,” she says. “Patrik said to his partner, ‘Think of me as if I’m not here, I’m just coming home to sleep.’ And it worked so well.”

Working with Nils Törnqvist and sound engineer Michelle Amkoff, the bulk of the work was done within the two weeks they’d originally planned for, though some parts were added later – guitar and flugelhorn from Julia Ringdahl and Ellen Pettersson of Hey Elbow, a piece for horns by arranger Ben Babbitt (Weyes Blood, Angel Olsen), and the album’s star turn from Mike Hadreas aka Perfume Genius, which arrived by email.

“We’d been writing to each other every now and then through Instagram,” Boman explains of the Hadreas connection. “It’s so easy to DM and just say hi, so I did because I’d been a fan of his for a while. At one point we’d talked about maybe doing a cover of ‘Storms’ by Fleetwood Mac, but that never happened. Instead, when I was making this album, I sent him a few of the demos and he picked out ‘Feels Like A Dream’ as one he wanted to sing on. I hadn’t written it specifically with a duet in mind but I’m really so happy with how it turned out. I think his voice is so, so special.”

Boman is no stranger to writing about love, but the twinkling “Feels Like A Dream” is the most she’s ever leaned into the romantic side of things. On paper, the lyrics can seem mawkish, but there’s a vulnerability to the duet that feels very in keeping with what’s come before. “Vulnerability is not something that I strive for, but I feel like it’s not something to try to avoid either,” she says. “What comes out, comes out.”

“So many of my songs have been about longing for love and the disappointment you feel when you think you’ve found it, but it ends. Everyone always told me: Once you’re in a relationship, it’s not like everything is just going to fall into place. You’re going to discover new sides of yourself when you get that close to another person. And I think a lot of that is on this record.”

Lead single “Night & Day” is a case in point. As someone who had wanted so badly to be in a relationship that lasts, Boman was confused by her own reticence when real love finally came along. “I was open and I was ready for it,” she explains. “But I wasn’t prepared for how scary it can feel to get close to someone. You have to sort of remember to allow yourself to just let go and dive into it, to not be afraid of being too much one thing or another and just be yourself.”

“It sounds so cheesy to say, but you do grow as a person when you’re in love, and I found it fun to observe and try to understand all those changes by writing about them.” She pauses and smiles. “It’s weird. I thought it was going to be so hard to write songs from being in a happy situation, but there was so much to talk about!”

It’s a slightly paradoxical claim from Boman, who – by design – gives only just enough away in her songs to anchor the emotion. The Space Between, at times, feels more tabula rasa than storybook. Songs like the flickering “In Circles” and “What Happens to the Heart” are left so purposefully vague they would feel almost vaporous if it wasn’t for the gorgeous instrumentals. Elsewhere, Boman sets out her motivations more clearly – in the sensual “On & On”, with its bedroom-pop beat, and the creaky, atmospheric “Soon”, with its plea to keep the channels of communication open.

Aware that she now has two sets of feelings to consider, Boman says she talked to her partner about how it feels to hear songs that, to him, are so clearly about their relationship. “He loves the songs and I think that’s beautiful,” she says. “I think the songs are still quite universal. They aren’t so personal that people can pin them on the two of us, and that’s what I want.”

On stage the next day, Boman seems to have got the better of any pre-show nerves she had been feeling. Never one to explain herself or her songs just for the sake of explaining, she keeps the stage talk brief, content to let the music say her piece. Singing her mantra-like songs under the intensely blue stage lights, under the stars, gives the feeling of some kind of incantation. To sing a line once is simple. To sing it twice can make it true. To sing it three or four times? That’s The Space Between for you.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Lorde

Virgin

OSKA

Refined Believer

Tropical F*ck Storm

Fairyland Codex