Activism and education meet music in Roskilde's modern utopia

Chris Taylor heads to Denmark's Roskilde and finds a festival fighting the good fight, even if there's work to be done on a truly equal line-up.

In 1971, Jacob Ludvigsen, a journalist part of the “provo” moment which was designed to rile up the authorities through non-violent means, opened the doors to Christiania. A former military barracks in Copenhagen, Denmark, it was to be a truly free town. In the words of Ludvigsen: “The objective of Christiania is to create a self-governing society whereby each and every individual holds themselves responsible over the wellbeing of the entire community.”

It’s an ethos that is surprisingly present around 30 kilometres to the west of Copenhagen too, in a place called Roskilde. For one week every year, Roskilde Festival becomes the fourth largest city in Denmark with approximately 130,000 people making it their home. In true Christiania style, it feels like its own free town. The emphasis, other than on showing some fantastic music, is to try and create a festival that feels more like a city ruled by the people for the people.

Here, camps are more than just a group of people stuck together; they’re actively encouraged to get to know their neighbours. The food stands are run either by local groups (such as handball teams) to raise money for their operation or by food professionals wanting to try out a new concept. There’s not a Pizza Express in sight. Festival goers even get the chance to make their mark on this “city”, whether that be by creating huge soundsystems, expressing themselves in graffiti workshops or even building a totally original camp such as the impressive Game of Thrones themed A Camp of Ice And Fire.

In a world that slowly feels like it’s descending into a farcical modern dystopia, it’s understandable why people would want to try and create their own utopia. It’s the reason why thousands kick up a dust storm racing to pitch their tents when the site opens.

But utopias are difficult to achieve. The name itself, a combination of two Greek words that together mean “no-place”, quite literally implies that there is no place where humans could be truly free. Coined by Thomas More in his 1516 book Utopia, it was nothing more than a fantasy. The names he coined for other places in the book, and even the names of some characters, were created to mock the idea that such a dream were possible.

It’s the fear that society’s ills would move into the utopian society with just as much fervour as the people themselves. Things like pollution, crime and corruption are often the downfall of such societies. Roskilde, however, are fully aware of these cons and is constantly taking steps to actively combat this year on year. Reacting to the negatives when they rear their head or trying to prevent them from happening at all to make the festival feel like an egalitarian oasis.

Last year, Roskilde’s organisers came under fire from Danish media for the festival’s failure to prevent sexual assault, with six rape cases reported. It’s something worryingly commonplace in the world of music festivals and not just something that Roskilde has to face. But rather than putting out a statement and moving on, Roskilde has taken steps to prevent future incidents. Under the banner “Orange Together”, Roskilde want to have those sometimes difficult questions that come letting people be free. Working with organisations like Everyday Sexism and the Danish Women’s Society, they even created a card game to ensure people can navigate the grey areas of drunken festival fumblings without harming anyone.

It’s not just about sexual equality either. Social equality (or inequality to be exact) is put under the spotlight, with food stands like Food For Fifty providing hearty, affordable meals for just 50 DKR (around £6), as well as talks, games and activities highlighting the economic inequality across the world. Giant border walls loom over on of the food area like spectres of what could be as countries close themselves off from others with increasing violence, while the “Serpent of Capitalism” wormed its way through the camp before being slain.

Even the food stands themselves are designed to educate people about the environmental impacts of their burger and chips, hoping the climate footprint cards that adorn each stand makes every visitor think twice about what they’re eating.

Then, of course, there’s the music. With 36 countries represented, and with 75% of artists having never played Roskilde Festival before, it’s a festival that wants to open your ears to new things. The end result is a line up that saw me catching cult Japanese composer Yasuaki Shimizu making unusually beautiful music with a radio at lunch time, before getting swept up in Stefflon Don’s energetic party anthems and Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’ gloomy desert sermons.

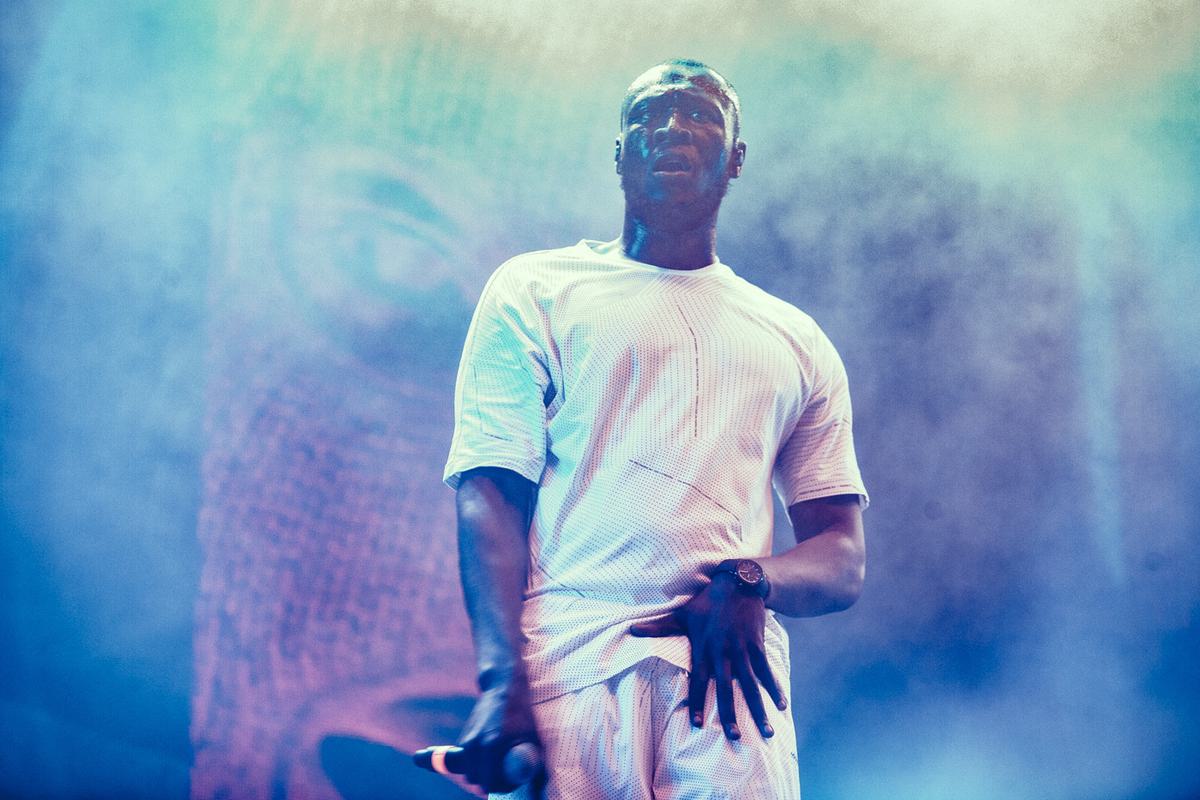

The big catch this year was Eminem, who the festival have apparently been trying to book for 17 years. With a record number of people filling every inch of space in front of the Orange Stage, it’s clear to see why. His collaborations with Rhianna, Ed Sheeran and Beyonce, as well as “Rap God” got big reactions, but his medley of classics sent the overwhelmingly gigantic crowd into meltdown. Stormzy, similarly, drew an incredible crowd, hoping to witness the same magic that went viral when he played here in 2016. Instead of dipping into the more gospel tunes that pepper Gang Signs & Prayer, this is all about whipping more frantic mosh pits. The likes of “Know Me From” and “Shut Up” do just that as the 24-year-old South London megastar stormed the stage.

Despite having a heavy focus on equality, however, Roskilde’s gender split isn’t quite as equal as you might expect. There’s far more women on the line up here than, say, Leeds Festival but it’s still not quite a 50/50 split. When only two of your main headliners across four days (St Vincent and Dua Lipa. Cardi B had to cancel due to her pregnancy) were women, steps need to be made there.

The emphasis on equality did weave its way into the line up in other ways, though. David Byrne, after a phenomenal set that included tracks from his Talking Heads days and some from his latest album American Utopia, ended his set with a cover of Janelle Monae’s “Hell You Talmbout”. A visceral protest song that saw him and his band paying tribute to black Americans that were killed by racial violence, it’s a powerful white man using his platform to declare that, after all the dancing and joy, we need to join the fight for a better world.

Similarly, First Aid Kit took to the Orange Stage with their furious anti-rape track “You Are The Problem Here”, proclaiming that the onus of blame needs to shift from the victim to the perpetrator. Not “what were they wearing or how drunk was the victim?” but “why did that person feel the need to rape?”

These proclamations weren’t falling on deaf ears either. Queues to get into the Gloria stage to see Chelsea Manning, the American whistleblower, talk about her experiences as an activist and as a trans person in the public spotlight showed just how important this quest to change the world for the better was to the crowd. The variety of other activists and politically-driven artists appearing, particularly in KlubRa, only cemented this.

People come to Roskilde not just to have a good time, but to actively engage in the things the festival believes in. It’s called the Orange Feeling, and the music plays just a small part of that.Wander through the dusty fields filled with tents covered in camp insignias or (more commonly) graffiti dicks and you notice that, even while the main area is in full swing, this is where the real Roskilde lies. People are going to watch the World Cup together at the big screen by the football and basketball courts, friends are heading down to the Food Jam to cook their own food from scratch, those with the soundsystems are setting up their own parties. The music is a nice added extra to this youthful utopia.

Yes, the camps may resemble (and smell) a bit like shanty towns than the utopic ideal. But you can’t have yin without yang. And Roskilde, with its “leave no trace” policy, attempts to keep the yang as a complementary, rather than opposing, force to the yin.

It is an incredibly bold claim to say that Roskilde Festival is, for one week, a utopia. But Roskilde is trying to change the world for the better, and gives the visitors the tools to try do that. Whether it’s helping to educate the youth on consent, giving artists and activists a platform of open ears to share their ideas, or just give people a chance to see some of the best music from around the world,

Roskilde is a place where people can be free. Free to experiment. Free to express themselves. Free to have fun. Free to change the world. What they do with that freedom is up to them, but when you walk off the campsite, you can’t help but feel that perfect, egalitarian society is not far off. Not today, not tomorrow, but soon.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Tunde Adebimpe

Thee Black Boltz

Julien Baker & TORRES

Send A Prayer My Way

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE