The Music of Studio Ghibli

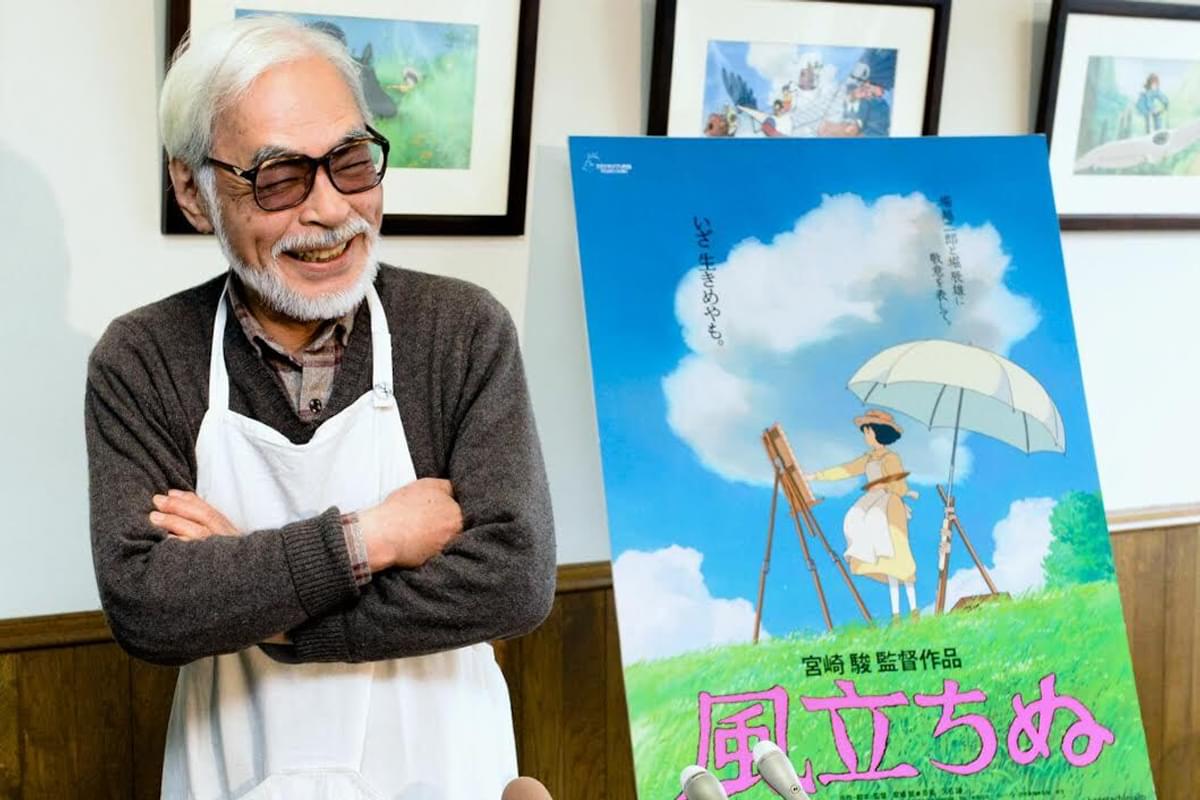

The somewhat over-exaggerated news that Japanese animation heavyweight Studio Ghibli is closing (it is in fact just going to restructure) comes just as the DVD of lead-director Hayao Miyazaki’s final feature, the historical biographical epic The Wind Rises, is released. As with the Ghibli's entire output, the film adds yet another dimension to an often overlooked side of the creative powerhouse: its music.

An appreciation of Ghibli usually brings the same themes to the fore: nature, technology, feminism, family and above all, humanity itself. Fans will recall a favourite film or scene, grounded in visual spectacle: that magical moment when Sheeta floats down to Pazu in Castle in the Sky, when the colourfully playful Cat-Bus leaps on to the screen in My Neighbor Totoro, or when the young witch Kiki first soars above the clouds in Kiki’s Delivery Service.

My most memorable moment is less visual in nature: the simple repeated use of Olivia Newton John’s cover of 70s country folk hit "Take Me Home, Country Roads" in 1995’s Whisper of the Heart. The song appears throughout the film in both the original cover at the beginning, and - later - performed the main characters with a violin accompaniment.

It's a relatively small part of the film, but the passionate childlike lyrics (the protagonist writes her own Japanese version complete with original verse, dubbed "Concrete Road") and appropriation of a folk classic works perfectly in the teen setting. That simple piece, along with the rousing string and woodwind led "Legend of Ashitaka" from Princess Mononoke; the whimsical, childlike delight and wonder-filled My Neighbor Totoro’s Opening Theme; the bedazzling, slow-building Chopin-esque waltz of "The Merry-Go-Round of Life" in Howl’s Moving Castle; the jauntily playful "Sootballs" of Spirited Away, and the soaring, accordion-infused "Journey (Dreamy Flight)" from The Wind Rises are my main signposts to this catalogue of incredible works.

Many of these pieces can be attributed to Joe Hisaishi (real name: Mamoru Fujisawa), also noted for his collaborations with Takeshi Kitano (the ridiculously prolific actor/director, and yes, also of Takeshi’s Castle fame). The long-time Ghibli contributor first joined forces with Miyazaki for the 1984 feature Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind - not officially a Ghibli-piece (the studio had yet to be established), but long since accepted into the fold.

The film is notable for its 80s synth-rock led tracks (such as "Ohmu no Bousou") often cited as slightly jarring when compared against the mainly traditional orchestral instruments used in the majority of the later films. Amusingly enough, the first ‘official’ Ghibli film, Castle in the Sky (1986), had its original synth-led score reworked with strings for its 1999 US re-release at the behest of Disney. Though Hisaishi, along with many other prominent classical film composers (ie John Williams) leans heavily on the works of early 20th-century composers such as Stravinsky, Prokofiev and Holst (among others), Joe also has significant nods to the less grandiose Debussy and Chopin, allowing the scores to be less imposing, more relatable and better suited for the character-based storytelling of Ghibli.

While his film scores rely on leitmotifs, as most soundtracks do, he isn’t weary of straying away from them and changing rhythms and timings to approach scenes in discernibly different ways, managing to mesh both the sentimental with the eccentric. His works ground the films’ historical and geographic influences, the bustling old late 19th-century houses come complete with matching waltzes and accordions, the futuristic apocalyptic backdrops, likewise with synths, and even the rural, fantasy landscapes are given appropriate grandeur with waves of strings.

If one criticism can be aimed at his method then it would be an over-focus on atmosphere, emotions and characters that causes his pieces to stray from the action taking place on screen. The result moves the music to backdrop rather than running commentary. This actually ties in with the rules of the animation house’s museum, where cameras are banned and instead visitors are encouraged to see the exhibits with their eyes and memorise their experiences, rather than spend time documenting everything for a later date.

The conflict in terms of musical styles in Miyazaki and Hisaishi’s final work The Wind Rises parallels the clash of ideologies in the story – the wonder, freedom and imagination all tied up with designing flying machines – set against the impending backdrop and overriding influence of the military and war. Hisaishi manages to balance both, on tracks such as "Caproni (Engineer’s Dream)" – where buoyant, cheerful pipes and strings are tethered down by the forceful, military weight of the horns and drums. That isn’t to say that the thematic ideas overshadow the character themes, with the various iterations of the stripped back Naoko’s theme resurfacing with dramatic prevalence throughout the film. It’s often hard to imagine that the same creator of such elegantly heart-felt, nuanced melodies could be the same architect of the bouncily silly nursery-rhyme-esque songs of Totoro and its spiritual successor Ponyo.

So next time you tumble down the rabbit hole into the animated wonder of this Japanese animation studio, don’t just focus on the beautifully crafted bursts of colour, fine detail and immersive magic, listen to Hisaishi’s audio mastery, which skillfully moulds, wraps around and projects the themes, characters and emotion onto the stunning canvas of celluloid.

The Wind Rises is released on Blu-ray and DVD on 29 September via StudioCanal.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Prima Queen

The Prize

Femi Kuti

Journey Through Life

Sunflower Bean

Mortal Primetime