Time's Arrow

Vilified by critics on release, Performance has become a defining movie of its era. As its fiftieth anniversary is celebrated with a new book, writer Jay Glennie reflects on the film's difficult birth.

"I wasn't aware that I wanted to make the move from being an agent into producing films, and meeting Donald Cammell, and subsequently Nic Roeg, meant I could make the move a reality,” recalls Sandy Lieberson on the decision to become a film producer and leave behind a successful career as an agent

Lieberson’s first film as a producer - Performance - is either ‘The most completely worthless film I have seen since I began reviewing’ (Richard Schickel, Time Magazine 1970) or as championed in 2011 by Mark Cousins in his fifteen part TV series The Story of Film: An Odyssey ‘…not only the greatest seventies film about identity, if any movie in the whole Story of Film should be compulsory viewing for film makers, maybe this is it.'

These appraisals, over 40 years apart, showcase the critical about turn Performance has undertaken. Almost universally vilified upon its initial release – one notable exception was critic Derek Malcolm who championed the film, proclaiming it to be 'richly original, resourceful and imaginative, a real live movie' - Performance is now seen as one of the seminal films of the last 50 years.

Film historian and author Colin McCabe hails Performance as the best British film ever made. But even before its release the film studio funding it were repulsed by its violence, drug taking and sexual morality.

Performance is the film that arguably defines the late 60s in bohemian London. The blurred lines of reality and fiction came together to tell the story of Chas Devlin, a gangster and diligent enforcer of the will of his boss, Harry Flowers. Killing a rival puts the fragile status quo of the London underworld at risk and forces Chas to run and look for refuge until he can slip out of England. A Notting Hill townhouse owned by Turner, a burnt-out rock star would appear to be the ideal short-term hideaway. That is until Chas allows Turner's ménage à trois to mess with his identity even further.

American studio Warner Bros, wishing to tap into the burgeoning youth market, financed the production in their misguided belief that they were buying into a film depicting the optimism and energy of swinging London; a new A Hard’s Day’s Night, complete with an accompanying album from the film's star, the biggest rock star on the planet, Mick Jagger.

Instead what they were handed was a heady cocktail of hallucinogenic mushrooms, sex - homosexual and three-way, violence, amalgamated identities and artistic references to Jorge Luis Borges, Magritte and Francis Bacon. Their star, Mick Jagger, failed to appear until nearly an hour into the film and only sung one song on the subsequent groundbreaking soundtrack by Jack Nitzsche.

After a string of number one singles – "(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction", "Get Off My Cloud", "Paint It Black", "Jumpin Jack Flash" – the Stones had released their seventh long player, Beggars Banquet, which longtime Stones engineer, Glyn Johns, called their “coming of age record”, to universal acclaim but not a little controversy, with the backdrop of the civil unrest providing the impetus for "Sympathy for the Devil" and "Street Fighting Man". Their success saw religious groups and the right wing media label the Stones a corruptive influence on the God fearing youth, the accusation being that they were in league with the devil. This furore did little to dent their success, indeed the group's popularity only soared to even greater heights. And yet it was not sustaining their front man, Mick Jagger. The singer was looking to break into movies, as Jagger himself said, “to take on a role because it’s more than just a pop star role.”

Sandy Lieberson was enthusiastic about this move, “It was always going to be Mick as Turner, as an agent I knew Mick professionally, as well as being part of a group of friends that include Robert Fraser, Marianne, Keith and Anita, Kenneth Anger, Spanish Tony etc...I had no doubts that Mick could do it. Donald, Nic and I were convinced he was completely right to play the rock star Turner in Performance. I knew that all the fame and notoriety surrounding him at that time of his life would be perfect.”

What was imperative to Lieberson was that any film that he pursue with Cammell and Roeg, "would be influenced by the times we were living in. Into that mix went the political, social and psychological mood sweeping across the world, and in particular for us in London."

The '60s saw class barriers come crashing down as gangsters, pop performers and film stars, mixed with aristocracy. London's Kings Road was full of androgynous looking males, eager to express their femininity. Performance co-directors Cammell and Roeg brought all this together in a melting pot, which would go on to revolutionise the film world. Their groundbreaking language of imagery was brought to life with non-linear storytelling and Roeg’s majestically lit cinematography asked audiences to assemble a celluloid jigsaw puzzle in order to fully comprehend and unlock the film’s mysteries.

Viewing the resulting film, Warner Bros. were horrified with their investment. Decrying the film's graphic and decadent drug use, violence and sexual content - Jagger and co-star James Fox were seen on screen enjoying drug-fuelled sex with Anita and Michèle Breton - they refused to release the film. “They thought it was dirty,” said producer Sandy Lieberson five decades later. Nic Roeg laughingly recalls fearing Warner Bros. were going to sue him.

Two years of financial wrangling, threats from from both the Studio, and ‘Vice. And Versa’ from Donald Cammell and Mick Jagger, ensued before the eventual release of Performance.

Set decorator Peter Young describes the location shoot as a division of two distinct camps - the "straights": the older experienced film personnel and technicians, and the opposing camp made up of those who wished to partake in drugs: “a looser kinda lifestyle” - ‘the cool set’. This highly charged atmosphere ensnared victims into its corruptive vortex. Despite proclaiming that Performance was the best performance he ever gave, afterwards James Fox would leave the industry for ten years. "When I had my Christian conversion in ‘69," he recalls, "My friend Johnny Shannon asked me, 'Do you want me to sort them out, Jim?' I thought that it was so super of him. He thought I had got involved with a real heavy cult who were going to take my money and screw my mind."

The extraordinarily bright, handsome, louche, charming Donald Cammell would see his co-director Nic Roeg become lauded as one of the great filmmakers, whereas his own career floundered in Hollywood. And it was in the Hollywood Hills in relative obscurity aged 62 that he would place a revolver to his head and pull the trigger, after completing only three more films - Demon Seed (1977), White of the Eye (1987), Wild Side (1995). Anita Pallenberg, the ultimate rock chick would begin her descent into drug addiction during filming, naively believing that she "had kept it from everyone." And as for the star, what became of him? Mick Jagger survived the shoot in one piece, is still touring with The Rolling Stones and is still arguably the greatest rock ‘n’ roll singer on the planet.

Sandy Lieberson once told me that a Nic Roeg film is only appreciated by a wider audience many years later and that chimes with Roeg’s collaboration with Cammell: Performance lives on and continues giving performances fifty years after its inception. Dean Cavanagh, Bill Nighy, Paul Schrader, Irvine Welsh and Stephen Woolley all spoke of the profound effect the film had on their subsequent work and careers. The films influence can be seen in the work of directors such as Martin Scorsese, Guy Ritchie, Jonathan Glazer and Quentin Tarantino. Musicians including William Orbit, The Happy Mondays and Big Audio Dynamite have all used the score and film as reference points and samples in their songs.

The Stones’ former manager, Andrew Loog Oldham said "the Stones were not to the celluloid manor born". And yet Mick Jagger's cinematic debut as the reclusive rock star Turner is venerated as one of the greatest performances from a musician in film.

The rising resentment against the ruling elite, thrown up and scattered across the globe in 1968, resulted in a seismic social and political change. "Performance was born out of that fervour and an understanding that we did not want to make a Hollywood movie. Donald, Nic and I wanted something that was going to rival the new wave cinema of France and Italy," says Lieberson.

It is no exaggeration to claim that 1968, the year the cameras rolled on Performance, was the year that changed the world forever. Christmas Eve saw the Apollo 8 spacecraft manned by Jim Lovell, Bill Anders and Frank Borman become the first manned spacecraft to orbit the moon. However, this proved to be a rare moment of good cheer in an otherwise challenging year.

Europe was rioting. Across France some ten million workers went on strike, virtually paralysing the country, in solidarity with students who had taken to the streets of Paris against the de Gaulle government, demanding reforms to their education system. "I happened to be the Stones’ office when Daniel Cohn-Bendit, leader of the '68 Paris riots and the student protest movement called after hearing "Street Fighting Man" to ask for Mick's support. I spoke to him and assured him that the Stones supported their cause," recalls Sandy Lieberson.

Central and Eastern Europe saw widespread protests against the restrictions on freedom of speech, resulting in the Prague Spring. The UK played host to frequent CND marches against the increasing fear of a nuclear holocaust. Conservative politician Enoch Powell’s infamous anti-immigration ‘river of blood’ speech stoked further fires.

The fear of an unwanted pregnancy had overshadowed any intimate relationship, but with the advent of the pill and the relaxation in 1967 of the draconian principle of only prescribing it to married women saw the UK finally attempt to shake off its Victorian attitudes to sex. The same year saw homosexuality decriminalised in England and Wales, despite the Home Secretary of the time, Roy Jenkins appearing to capture his government’s attitude when he was quoted as saying during a parliamentary debate, "those who suffer from this disability carry a great weight of shame all their lives."

The Black Panther Party came to a wider public consciousness when two black American athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, were sent home from the Mexico Olympic Games after raising their black gloved fists in the Black Power Salute during their medal ceremony. The year also saw the tragic assassinations of both Dr. Martin Luther King Jr and Presidential hopeful, Senator Robert Kennedy, only adding further fuel to the civil rights protests raging across America. The bloody Vietnam Tet Offensive saw even more American soldiers arrive home on US soil in body bags, resulting in frequent demonstrations against further US involvement in the war. "We also protested the Vietnam War here in London," remembers Sandy. "Mick, Donald, Robert Fraser and I spent the afternoon cheering on Vanessa Redgrave in Grosvenor Square."

Television audiences in the US witnessed the first interracial kiss when Star Trek's Captain Kirk kissed Lt. Uhura. The year before at the 1967 Academy Awards Bonnie and Clyde, In The Heat of the Night and The Graduate were all nominated for the Best Picture Oscar and the following year studios released genre defining films such as Rosemary's Baby, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Planet of the Apes, Teorema and The Boston Strangler, so the times were a changing and it appeared that film audiences were ready for a film with a great musical score, depicting the coming together of gangsters, rock 'n' roll, drugs and free love.

And yet like a fine wine it would take a little patience and time for Performance to breathe before a wider audience caught on.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

070 Shake

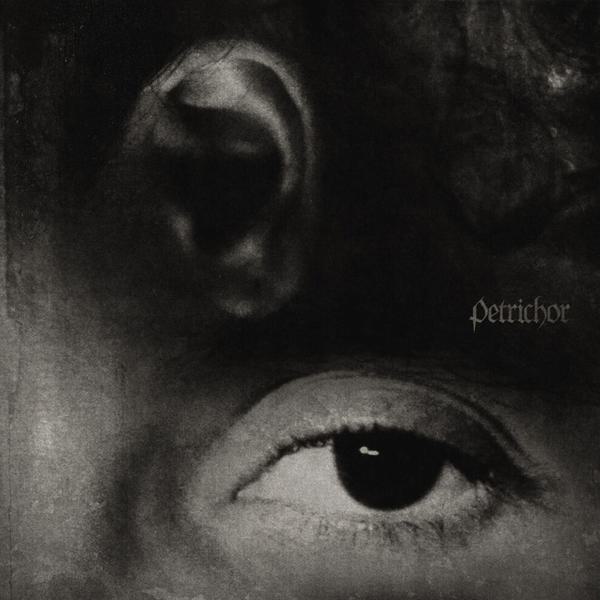

Petrichor

Kendrick Lamar

GNX

Father John Misty

Mahashmashana