Old man, look at your life: A 70th birthday appreciation of Neil Young

Neil Young - who turns 70 today - changed my life.

Before you place an emergency call with the hyperbole police, allow me to inject a bit of context. When I was younger I had no discernible interests. It was obligatory for any adolescent male in my native Finland to go through the devil's horns-flashing ritual known as the Metal Years, so that's what I did, albeit without any mad levels of allegiance to double bass drum pedals, spandex, demonic affiliations and supersonic guitar twiddling.

With Iron Maiden and Metallica as my points of reference, imagine my surprise - shock, more like - at encountering a cut off Young's 1990 LP Ragged Glory, recorded with Crazy Horse, still by some distance my favourite backing band; not just for Young, but anyone. This music was keen on flexing its muscles, too, but it was a very different kind of aggression from the death-obsessed grunting and eternally adolescent angst I'd grown accustomed to. These guys played what can only be described as hard rock like they held a deep-seated resentment towards their instruments, but it somehow came across as a positive undertaking, due not least to the simple but strong melodies and the angels-with-stubbles harmonies their thudding, unhurriedly evolving minor-key jams were slathered with; later I found out this may have had something to do with Young & Crazy Horse's enthusiastic participation in the original hippie era, the enduring whiff of which lingered on. There was an earthy groove to this stuff, too, a colossal yet slightly unsteady, hypnotic gallop that sounded like it could go on for hours - and frequently did.

Most of all, the guitar sound was unlike anything I'd come across, a protean, fuzz-coated howl that suggested the soloist's equipment had been marinated in mud for a few decades and had only undergone a cursory clean-up before being dragged back into active duty. Young's wilfully sloppy solos, frequently shot through with flights of lyrical beauty that were all the more startling for residing next to extended squeals of moaning feedback, were a billion miles removed from the skilful but antiseptic technical excellence that passed as 'good' musicianship; this guy played - and sang, in a high-pitched whine that sounded not unlike a cat in distress, only a whole lot more pleasant and expressive than that - like he meant every note, even the fluffed ones (man).

In short, I was impressed, a mega-fan for life after just five minutes' exposure, even more so when I realised that this relentlessly energetic, soulful sludge had been whipped up by a man as old as the hills who'd already recorded something in the region of a thousand albums, most of which (apart from much of the 80s, when Young battled the double trouble of waning songwriting inspiration and a swap from long-term label Reprise to Geffen Records, who wanted the Ontario-born legend to do the one thing he's totally incapable of: stay the same) as good or even better than Ragged Glory.

This interest - no, obsession - in Young's music led to further musical explorations, which in turn led to discoveries in books and films and, gradually, widening horizons in general, too. Although my musical interests have since expanded far beyond Young's country/folk/rock domain, I'm yet to find anything that hits even half as hard as Young's finest output. His is a discography that keeps on evolving and growing in depth over time: albums like 1978's bittersweet Comes A Time, for example, sound completely different once you're old enough to have experienced the changes he's singing so beautifully about over a rich Countrypolitan orchestra, itself barely recognisable as the work of the same artist responsible for the raw garage-rock anthems of 1975's Zuma or 1979's punk-influenced blast Rust Never Sleeps. Having tackled anything from plaintive piano ballads ("Love In Mind", "After The Gold Rush"), psychedelic splendour ("Expecting to Fly") and solo folkie fare ("Will to Love", "Tell Me Why") to slow-burning guitar odysseys ("Down By The River" with its one-note solos, "Love to Burn"), groovy folk-rock ("Winterlong", "Everybody Knows This is Nowhere") proto-grunge rockers ("Cinnamon Girl", "Powderfinger"), bluesy laments ("On The Beach", "Don't Be Denied"), sparse balladry ("Helpless", "Only Love Can Break Your Heart"), countrified confessionals ("Old Man", "From Hank to Hendrix") and what can only be described as novelty songs ("This Note's For You", "Piece of Crap"), Young really does have a song - and record - for every mood. So, if a person's life is shaped by their interests, what they're into, what moves them, Neil Young really has changed my existence - for the better.

I'm far from the only one to feel this strongly about the Canadian but California-based legend's work. Wilco's Being There, Ryan Adams' Heartbreaker, Gillian Welch's Time (The Revelator), My Morning Jacket's It Still Moves and, most recently, Israel Nash's Silver Season : Young's sparse, finesse-averse, ever-evolving spirit hangs over much of the finest produce in the Americana/alt. country idioms like a Batlight with no off switch, and there's barely a decent songwriter around who doesn't owe at least a small debt to Young's unique blend of melody and discord, heartache and grit.

What's more, Young pretty much wrote the book on how to place art before commerce during his creative peak in the 70's. Having hit the big time with 1972 US number 1 album and single combo Harvest and "Heart of Gold", the one entry in Young's catalogue that could be mistaken for the laidback navel-gazing of the original singer-songwriter, were it not for the heart-rending horror of anti-heroin creed "The Needle and The Damage Done" and the weary thud of "Words", he reacted to the newfound fame and fortune by making music that's guaranteed to unsettle anyone who's in the market for some easy-going, sweetly sad background music. The outcomes - 1974's On The Beach, 1975's Tonight's The Night - count amongst some of the rawest, most real and uncut music ever issued for public consumption by a major star. When the prevailing trends of the era called for months spent in the studio, polishing the product until no edges remained, Young headed the other way, favouring first takes and audio verite approaches - large parts of Tonight's The Night were recorded hammered, in a kind of wake to original Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten and CSNY roadie Bruce Berry, both lost to heroin - that rendered many of his studio albums live records, too; remarkably, this proved a recipe for renewed commercial success towards the end of the 70's.

During his 90's comeback as the Godfather of Grunge, revered as a major inspiration by the likes of Sonic Youth, Nirvana and Pearl Jam (who recorded 1995's frenzied if uneven Mirror Ball with Young) after a difficult decade mostly spent in the wilderness of unbecoming genre experiments such as 1982's synth-pop Trans and 1985's old school country workout Old Ways (although following Geffen's insistence for rock 'n' roll with 1983's flimsy rockabilly pastiche Everybody's Rockin' is a cantankerous masterstroke, if not exactly an artistic triumph), Young followed 1992's huge-selling acoustic gentleness of Harvest Moon with the dark, brooding and profoundly strange Sleeps with Angels, the one Neil Young (and Crazy Horse) album that gains hugely from staying well away from his usual default settings. Along the way, Young's wilful insistence on doing what feels right today as opposed to what the label's release schedule dictates has led to the last-minute scrapping of such legendary lost albums as Chrome Dreams (1977) and Homegrown (1975), summary dismissals of bands (Crazy Horse has been dropped and regrouped with regularly since their inception with 1969's classic garage-folk-rock opus Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, likewise hard-living Woodstock generation "supergroup" Crosby, Stills and Nash) and instant recruiting of new ones, and rapid swaps from acoustic heartbreak to feedback-bingeing guitar-baiting, the sudden swerves executed with little thought for audience expectations or commercial considerations.

Admittedly, the ethos of instant creation and aversion to editing, second thoughts and listening to anything but the muse that worked so, so well when classic songs were pouring out of Young faster than he could record them has turned into an acute liability as inspiration's gradually turned into perspiration. While his contemporaries have either slowed down their release schedule or eased into the irrelevance of cosy nostalgia and cashing in on past glories (which Young has toyed with in the form of the ongoing Archives and Performance Series releases, which predictably enough follow no chronological or thematical logic), Young's continued to maintain the hectic productivity of the 70s, whether or not he's anything of much value to say. Whereas it once seemed like a much better idea to issue rough, incomplete takes of vintage Crazy Horse epics "Cortez The Killer" and "Like A Hurricane" than risk overcooking the magic in search of technical precision, the half-baked nature of this year's anti-corporate greed protest The Monsanto Years - alongside 2009's underpowered Fork in the Road and 1986's ugly-sounding AOR abomination Landing on Water, one of very few Young albums with no redeeming features - just comes across lazy and uncaring, almost as if Young (whose willingness to take a stand and use his status to drag unpopular issues - Young's been a vocal opponent of the tar sands oil extraction in Alberta, Canada, as well as investing time and cash into electric car technology and, less inspiringly, banging on about digital audio quality differences only a dog could distinguish without pro equipment - to the spotlight even when it risks alienating chunks of his audience has to be applauded, loudly) is aware that songs this insubstantial wouldn't be much improved by coherent arrangements.

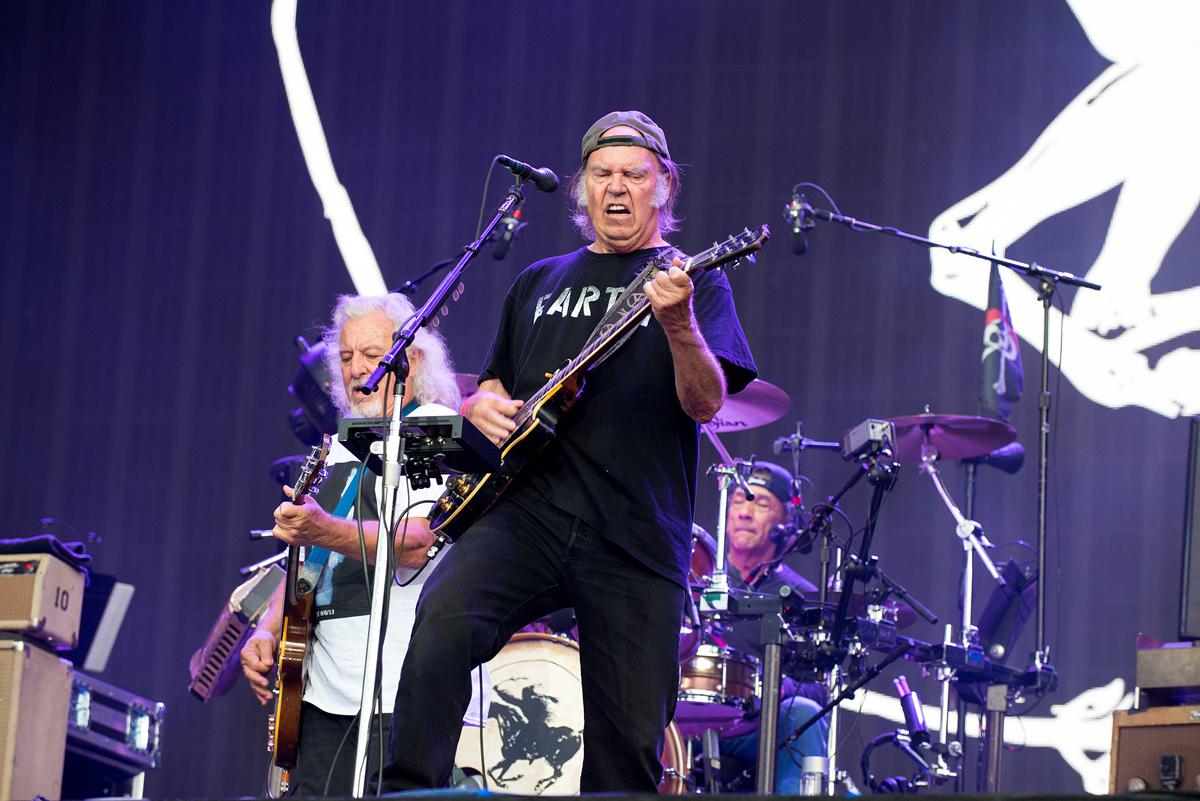

That said, 2010's solo electric, Daniel Lanois-produced Le Noise and especially 2012's self-indulgently sprawling but supremely spirited, long-overdue Crazy Horse reunion Psychedelic Pill prove that Young can still conjure truly compelling music, and even such profoundly uneven latter-day albums as 2003's Greendale, 2007's Chrome Dreams II (in a typically unfathomable Neil Young move, a sequel to a record that was never released) and 2014's over-egged orchestral workout Storytone contain at least one killer cut. Young's lyrics have become a whole lot clunkier over the years, but 2011's autobiography Waging Heavy Peace - fittingly equal parts beguilingly insightful and frustratingly prosaic, with the follow-up Special Deluxe going a bit too heavy on the latter - showed that he can both write engagingly and be as quirky in his prose as in his musical journey. Young also remains a uniquely enduring live act, with both his voice and musicianship unaffected by advancing years: 2013's UK dates with Crazy Horse won entirely deserved rave reviews and the extensive shows during Young's recent US tour with Promise of the Real have dug into the deepest recesses of his excessive back catalogue, indicating that Young remains resolutely uninterested in coasting on the 'hits'.

What's really impressive about Young is that at 70, it remains pretty difficult to guess what he'll do next, although it's safe to bet it won't involve doing the done thing. Fittingly, the point at which Young's longevity finally makes him the antithesis of his last name is accompanied by a new release, this time one of Young's many lost albums, a double live album cut with his short-lived rhythm 'n' blues outfit The Bluenotes in the late 80's, originally slated for release in 1988. That Bluenote Cafe pops out now, 27 years later, on Young's 70th birthday, might suggest some greater significance to its author that the spirited but slight saloon bar Blues grooves (including songs Young wrote for his first band The Squires in the mid-60's) that make up most of the record don't quite explain. The Bluenotes phase stirred up Young's songwriting prowess, leading to Young's comeback with 1989's Freedom - starring "Rockin' In The Free World", a deeply sarcastic protest song as widely misunderstood by flag-waving politicians as "Born in the USA". Perhaps Young sees some parallels with his ongoing work with the young musicians of Promise of the Real. Whatever the case, Bluenote Cafe is a typical Neil Young album in that it features a handful (virtually leaping out of the speakers, this take on "Crime In The City" makes the fine Freedom studio version sound toothless) of cuts every fan should hear. The energy and enthusiasm on display, meanwhile, makes even the more meagre offerings interesting. On 1988's This Note's For You, "Twilight" is little more than a generic rhythm 'n' blues smoocher; here, with Young pumping more and more intensity into every verse and flurry of solo guitar, it becomes truly compelling. You could almost imagine someone being exposed to Young's music for the first time through this performance feeling an overwhelming need to hear as much of the man's music as possible, much as I did all those years ago.

Forever Young: Seven hidden gems from Young's latter-day albums

“Safeway Cart” (1994)

"Prime of Life", "Driveby", "Western Hero", "Change Your Mind": Sleeps with Angels is full of overlooked gems, but this spooky ambient glide through deserted city streets might just be the most potent example of the album's atmospheric, melancholy mood.

“Philadelphia” (1993)

A serious contender for Young's most moving piano ballad, this haunting, hymn-like gem, sung from the perspective of a person at the end of their life, written for Jonathan Demme's HIV/AIDS drama of the same name, glides on an almost supernaturally beautiful, delicately ghostly melody.

“Scattered” (1997)

The studio cut on 1996's rough Broken Arrow is fine, but this slowed-down live take off 1997's Year of the Horse - a kind of soundtrack to the engaging documentary of the same name that, in a typically contrary Young move, contains not a note of music heard in the film - captures Crazy Horse at their majestic peak.

“The Great Divide” (2000)

The song itself – off slight but pretty Silver & Gold - is fairly standard-issue acoustic Young, but the carefully layered production - by Young with long-term collaborator, the late pedal steel virtuoso Ben Keith - elevates the source material into pure gold.

“Bandit” (2003)

Hidden amongst the turgid two-chord tune-dodging of ecologically themed garage-rock opera Greendale lurks one of Young's most haunting latter-day laments.

“Ramada Inn” (2012)

"Walk Like a Giant" might pack more memorable guitar-wrangling but this carefully sketched portrait of a long-term marriage pushed to the edge by alcohol and resentment is the highlight of Psychedelic Pill, and quite possibly Young's strongest single song since the mid-90's.

“Glimmer” (2014)

Even a lavish orchestral arrangement more befitting of a particularly saccharine Disney flick can't hide the raw ache of this look at the end of a long relationship off Storytone.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE

Mamalarky

Hex Key

Florist

Jellywish