Sufjan Stevens delivers a passionate plea for love through Javelin

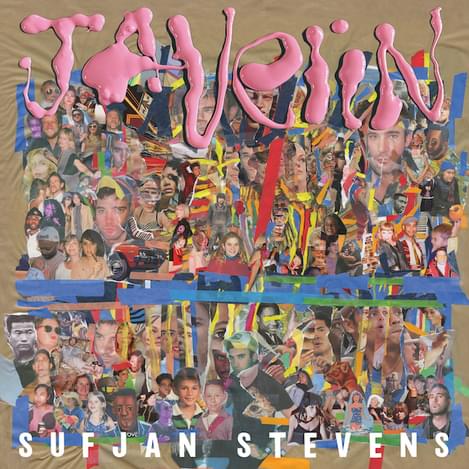

"Javelin"

Sufjan Stevens has been through a lot.

His decades-long career has made him the self-described “poster child of pain, loss, and loneliness.” And sure, he’s made sad music across genres from IDM to minimalism – but when the melancholy is most acute, he channels it into singer-songwriter music.

Javelin is Stevens’s first singer-songwriter album since 2015’s Carrie & Lowell, one of the most touching, emotive albums in recent memory. Since then, Stevens has released a smorgasbord of collaboration albums, a five-volume compilation of ambient music, and an eighty-minute pop voyage in The Ascension. On this album, Stevens goes back to what he does best – slightly electronic folk music paired with poetic lyricism – and he crafts yet another masterpiece, distinct from his previous catalogue but just as affecting.

Whereas Carrie & Lowell explored the death of Stevens’s mother with heart-rending thoroughness, Javelin seems to be about a different kind of loss: breaking up. A sense of profound longing underpins every song on the album – desperate pleas to an unnamed love for affection, coupled with the setting-in realization that things will never be the same as they were. “So you are dreaming of after, was it really all just for fun?” he sings on the devastating “So You Are Tired”. “I was the man still in love with you, when I already knew it was done.”

But a raw confessional this is not; like Stevens’s previous works, Javelin is, at first glance, anything but immediate. Listening to and unpacking Javelin is like staring into its collage album art: picking out details from a series of vignettes, slowly piecing together the story at the core of it all. Few details are given about the album’s subject, or really about anything – the entire album is shrouded in Stevens’s signature poeticism.

At its core, though, is a visceral nature: his lyricism spares most of the specifics in favour of communicating the most universal feelings of post-breakup introspection and pain. He pivots between pleading (“Kiss me with the fire of Gods, just say what you want / Say it out within, without that funny little cough”), pained acceptance (“Goodbye evergreen, you know I love you / But everything heaven sends must burn out in the end”), hopelessness (“Will anybody ever love me? / For good reasons, without grievance, not for sport”), and admissions of guilt (“Deliver from me from everything I’ve put off and know that we’ve lost”), refusing to follow a linear path from bargaining to acceptance. Even closer “There’s A World,” a stunning reworking of a not-particularly-great Neil Young deep cut, purports to be hopeful – but, especially after nine straight tear-jerkers, it plays like Sufjan is trying to convince himself more than anyone of the song’s rudimentary optimism.

The best Sufjan Stevens folk songs – “Mystery of Love,” “Fourth of July,” “Futile Devices” – belie a similar complexity in their instrumentals as much as in their writing, buried within deceptively simple melodies and structures that feel like they’ve existed since the dawn of time. They’re folk in every sense of the word. And, somehow, nearly every track on Javelin manages to evoke that feeling. Each song begins with only an acoustic guitar (sometimes a piano) and Sufjan’s whisper-sung vocals – as if it hurts to even sing. Then, they evolve: subtle electronics and choral vocals pile on, adding an immense atmosphere but maintaining the fundamental simplicity at the album’s core. It’s a formula that works perfectly each time, presenting the vastness of Stevens’s emotional turmoil with the subtle grandeur that it deserves.

Javelin is as far as possible from the eclectic art-pop of The Ascension or The Age of Adz, but it’s not quite as stripped-back as Carrie & Lowell or Seven Swans either. Javelin is, rather, an amalgam of his many influences; a distillation of Stevens’s lengthy career down to its most essential elements, expanded into a formidable plea for acceptance in a world seemingly turned against him. Even for one of the most talented and consistent artists of our generation, it’s a unique triumph.

In a booklet accompanying Javelin, Sufjan Stevens presents ten mini-essays: the first one begins by describing his fetal self, in tune with “the music of the heartbeat of the universe,” and the final essay is a surrealist piece about rebirth after being “swaddled into a warm cocoon of maroon goo.” It begins and ends in a rapture of sorts. And such is the ethos of Javelin: a deeply personal, Earth-moving masterpiece exploring relationship tensions with the gravitas of an apocalypse and the simplicity of a melody passed down through generations.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE

Mamalarky

Hex Key

Florist

Jellywish