ANOHNI inspects the intergenerational effort in achieving freedom on My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross

"My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross"

There’s an intonation of resolute yet unwilling resignation on ANOHNI’s first album with “the Johnsons” band name in 13 years.

Amidst the erosive and apoplectic wails of (reportedly) a lemur on “Go Ahead”, ANOHNI, having had enough of fights with obstinate minds, barks, “Go ahead / Kill your friends / I can’t stop you.” The reserved anger and provocative irony apparent on 2016’s solo project HOPELESSNESS seem to persist on My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross, a new album produced by Jimmy Hogarth and the collaborating band that highlights the early days’ pioneers, exploring ideas via mindful recollections and frustrating observations. In the historical context, “Go Ahead” could be a reprimand for those anti-LGBT malefactors who incessantly attacked gay bars in the 60s, which partly helped stir the Stonewall uprising, one of the most significant turning points for LGBT rights in America.

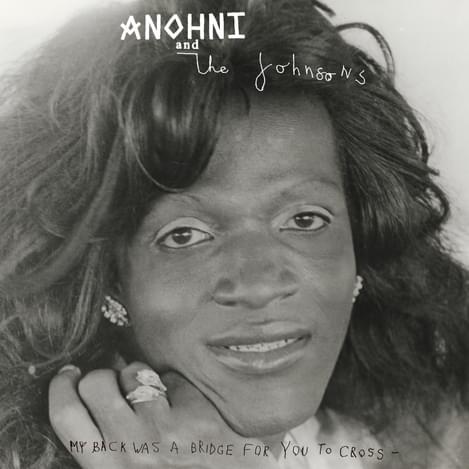

But instead of returning the blow as Marsha P. Johnson, the beloved activist whose majestic portrait appears on the album cover, did during the riots, ANOHNI stands back and watches them choke on their own hatred and prejudice like a resigned rebel. My Back, released under the restored band name, places its mythos in this attitude: vocalising the issues, not furiously biting back. As stated in the press, she intends to externalise a mutual awareness that makes people feel less alone. Such intention is redolent of timeless masterpieces like Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On (a confirmed inspiration) and Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions. The opener “It Must Change” is startlingly similar to “Save the Children”, both calling for an absolute change in whispers and marvellous vibratos.

Soul music in the 60s and 70s – the period ANOHNI references – was often used to vocalise the social and economic predicaments of the Black community and provide possible solutions to them. She, alternately, applies soul elements to survey subjects outside this origin. “Scapegoat” is a broad, unapologetic protest anthem with its anchor hung on minority hatred (“This one we need not protect / This one’s a freebie for our guns”); “Rest”, on the other hand, takes a more personal approach as she mourns for a collective loss, her grief shuffled in between intervals of Pink Floyd–esque rock. Unlike HOPELESSNESS, My Back meticulously retraces the outlines of the past and inspects the intergenerational effort in amending the hornet’s nest, that is, human society.

Its critical darts aren’t only thrown at world-scale leaders and political parties either – but also at herself, since most songs end up forging a personal connection with them. “It’s My Fault” is a stricken confession of her indirect contribution to Earth’s catastrophe, sealed with a plea for self-redemption. “It’s my fault the way I broke the Earth,” she whines. “My mouth to the stone / Feed me, I groan.” On the unadorned “There Wasn’t Enough”, she realises that she’s “not enough” to halt the impending cataclysm. “An offering like this won’t fill your soul,” she finishes, crushed with despair. Being born on Earth, one’s already bound to plead with Her for resources integral to one’s survival; this dawning pains her greatly as an environmentalist, hence the bubbling desire to set things right.

My Back values intimacy and honesty, the principles she’s followed since the Antony and the Johnsons days, namely the self-titled and the Mercury Prize–winning I Am a Bird Now. The difference is that the instrumentation on My Back is gentle, self-conscious, and loose in structure while that on her earlier works is poised and intricate. This rawness doesn’t make it any less powerful; it intensifies the despondency haze that hangs in the air of each song like a yet-to-rain nimbus. The stunningly arranged “Why Am I Alive Now?” is an excruciating resignation letter: her voice trembles, struggling to mouth her distressful words, as she wonders why she’s still here, on the brink of inevitable collapse. “I don’t want to feel this aching colour of our world,” she cries, her voice submerged under luscious riffs.

Under the reverberating strings and rigorous drum pattern, ANOHNI ultimately bellows in defeat, “I don’t know why I am alive now!” It’s a crucial, poignant opus that also states the album’s thesis: while not quite done yet with grieving, she’s passing the torch on to the next generation, hoping that they’ll carry on fighting for the Earth and powerless minorities, like what Marsha P. Johnson did to her, Marvin Gaye to Michael Jackson, Audre Lorde to Kate Rushin. “My back was a bridge for you to cross,” she mentions the album title for the first time on the final track before casting the last words: “You be free / Be free for me.” She’s learned that freedom is a continuing, intergenerational acquisition; in this cultural and ecological continuum, it’s a promising possibility that we as a force must never, ever relinquish.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Bon Iver

SABLE, fABLE

Mamalarky

Hex Key

Florist

Jellywish