The Weeknd's plunge into the pop mainstream is very well-packaged, but ultimately unrewarding

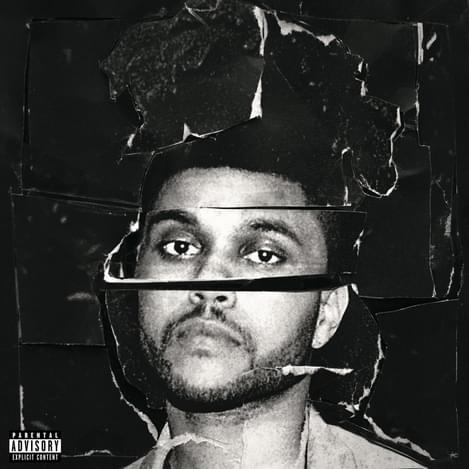

"Beauty Behind the Madness"

When The Weeknd broke around 2011 with a triplet of mix-tapes serialised a year later on Trilogy, Abel’s haunted portraits of fucked up nights/mornings/afternoons in Toronto were lucid and fascinating - sometimes ugly, sometimes beautiful. On his long-awaited follow up, Kissland, Abel transported these same themes into a new, alien setting: global fame, and all the disjuncture and chaos accompanying celebrity and notoriety. Only instead of using this new, amplified weirdness in his personal life as a catalyst to break out of the eerie, insular prism of Trilogy, Kissland continued on in the same vein, almost lethargically. Which might not have been so disagreeable had the writing been more adventurous or, even better, more self-aware.

On Beauty Behind the Madness we encounter Abel in much the same place, finding little beauty behind whatever madness is actually supposed to be unfolding, finding little of any substance at all. The problem though is that we’re offered no fresh perspective on this cycle of spectacular self-absorption, hedonism and self-destruction. There’s a frustrating sense that we’ve been here before.

As on Kissland, Abel repeatedly slipped into stark self-parody. It might be tempting to treat the superficiality in a lot of Abel’s writing as in some way artfully constructed, as faithful to a kind of reluctance on his part to assess the extent of the damage done. Except, this was what informed his older records; hearing it all over again only feels like running headlong into genuine artistic impasse. There appears to be no real motivation to portray this gross spectacle in any new or interesting light ("I just made another killin’/Imm’a spend it all on bitches/Everybody’s fucking, everybody’s fucking/Pussy on the house, everybody fucking," is one such example), and there’s little evidence of Abel transcending or subverting his status as the depressive protagonist, clinging to a bottle of Alize and sulking disconsolately in the corner at a party. Come the big confessional, you’ve stopped caring; lines like, "I’m a prisoner to my addiction/I’m a prisoner to a life that’s so empty and so cold/I’m a prisoner to my decisions," are so well worn they regress into wholesale caricature.

There is however greater affection, sensitivity and a more serious love focus on this record. Whether that’s Abel tentatively negating it (“To say that we’re in love is dangerous”) or blindly pursuing it (“Even though you’ll break my heart, my heart/Imm’a need you”.) And Abel’s vocals do a good enough job at conveying this agony. How much you actually care is a different matter. Because these relationships are rarely anchored with a sense of place or persons, to bring any of what we hear to life. The imagery is limited, and there are no real events (bar the fucked up phone calls at half-past five, on "The Hills") and little conflict external to Abel’s tiresome vacillating and incessant fretting.

Even the love interests, who are ostensibly so central in this drama, are deprived of a voice of their own: it’s Abel who invariably speaks on their behalf (“That’s why you always call me/Cause you’re scared to be loved”.) It all starts to sound a bit delusional. The only properly tangible narrative that doesn’t take place entirely in Abel’s head is found on "In the Night", a genuinely baffling attempt to tell the story of a girl (it’s inferred she's a stripper) damaged by a sexual trauma in her childhood. It’s a particularly egregious piece of storytelling that doesn’t even try to understand its complex subject matter. There’s no attempt to bring this character to life. She exists merely as a set piece, enabling Abel to thrash out some glaringly reductive thesis on trauma and sexuality ("In the night she hear him calling/In the night she’s dancing to relieve the pain"), all on top of an incongruously anthemic instrumental piece.

Of course classically in R&B lyrics themselves are somewhat secondary to the delivery and structure of the vocal performance. However the writing should at least invite intrigue, and it’s hard to be even partially involved in what’s going on here. There’s a reason: Beauty Behind the Madness is effectively a collection of individual pop singles, and most pop singles don’t tend to depend on imaginative, panoramic writing to be commercially successful.

With that in mind, there are some good - and a couple of great - pop singles on this record. Sonically, Abel’s abandoned the unstructured abstraction in his earlier material (songs that would trail boundlessly for up to eight minutes) for a more disciplined and conventional approach to making chart hits. And it’s what saves this record. Because if on the whole this album is a bit directionless, then the individual tracks have at least benefited from a lesson in cohesive song building. The spine of this thing is emphatic and infectious hooks, decent singing and solid instrumentals. In fact, there’s a run of tracks – "Tell Your Friends" (with a sumptuous soul beat sculpted by the ever infallible Kanye West), "Often", "The Hills", "Acquainted" (a nostalgic nod to an older Weeknd aesthetic), "Can’t Feel My Face" – which presents some of the most consistently enjoyable and immediately contagious moments in The Weeknd’s entire discography. And the closing track, "Angel" – a comically overblown ballad complete with big 80’s drums, choirs and pianos – is cool partly because it’s the only thing on here done with a clear sense of knowing, and perhaps even a smirk.

Abel’s plunge into the fast currents of the pop mainstream is largely a success - if that success is judged on how much an individual piece of music is marketable, digestible, and indeed enjoyable. Which is fine. But ambitious pop music is something very different: it’s cleverly subversive and keenly self-aware; and you get the impression on this record, as before, that Abel doesn’t recognise when he’s repeating himself. Get past all the exterior changes, and Beauty Behind the Madness actually reveals itself to be quite a safe, risk-free transition for Abel. This is the same old monotonous Weeknd melancholy, only distilled through a huge pop filter. Which certainly makes it listenable, and a little bit nicer, but far from the innovative mainstream breakthrough album we were promised. Abel is evidently very good at making big ubiquitous pop hits. He remains, however, incapable of seeing or writing outside of himself.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Prima Queen

The Prize

Femi Kuti

Journey Through Life

Sunflower Bean

Mortal Primetime