On The Monsanto Years, Neil Young's righteous anger fails to fully ignite

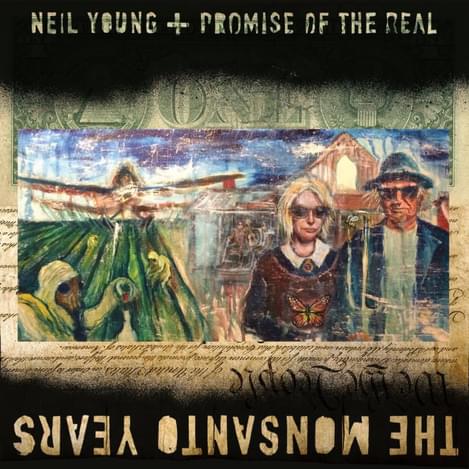

"The Monsanto Years"

It's a classic example of a politician completely misreading a song by struggling to sniff the ambiguous but clearly present anger lurking beneath the fist-pumping exterior. There's no room for such misinterpretations with The Monsanto Years, named as an anti-tribute to a multinational agricultural giant with interests in genetically modified crops and pesticides.

"Rockin'..." expects the listener to decode what the song's carefully crafted scenarios really stand for, and just how much acidic sarcasm the heroically rousing chorus is infused with. These nine tracks, meanwhile, deliver their unsubtle point with the blunt force of a hammer beating a simple message into our skulls, defying the listener to disagree, and disallowing any shades of ambiguity to interfere with the black/white, good/bad worldview.

Such unyielding certainties aren't necessarily a bad starting point. The best parts of Young's decidedly patchy 2006 anti-war workout Living With War derived plenty of righteous anger from a similarly direct approach. 1970's "Ohio" - arguably one of the most compelling protest songs ever - described the shooting of protestors at Kent State University in the style of a poetically penned newspaper clipping. The Monsanto Years, however, fails to accrue similar potency.

First, the positives. It's inspiring to see Young use his status to rally attention to the causes he supports; occasionally, it's hard not to detect an element of bandwagon-jumping when musical acts get political, but Young's clearly 100% committed to the ecological causes he’s backing, even when the activism risks alienating chunks of his audience. Teaming up with the Promise of The Real (featuring country giant Willie Nelson's sons Lukas and Micah) proves a good move, inspiring some fierce guitar duels and sweet harmonies, and generally infusing the proceedings with a ramshackle country-rock charm that's more than a bit indebted to Young's 70's masterworks. Most of Young's contemporaries have retreated into irrelevance, releasing far less new music than reissues of old favourites. It's impressive to see the 69-year old maintain a release schedule that would make many acts 40 years younger whimper with exhaustion: this is the Canadian legend's sixth studio album since 2010.

By now, the outcomes of the relentless productivity smack far more of perspiration than inspiration. Young's always been more interested in feel than finesse. Rightly so, as he's usually been able to turn his weaknesses - the odd fluffed high note, wavering tempos - into assets. Here, the stumbles and pitch-dodging vocals stink of an unwillingness to give up on a one-take dogma that worked so well on, say, 1990's Ragged Glory long after it's ceased being a creatively fertile strategy. Too often, these cuts sound like initial rehearsal run-throughs, captured and stored away well before the musicians have figured out how to navigate the songs properly.

The Monsanto Years also marks the point where the songwriting rejuvenation evident on the best parts of 2010's Le Noise and 2012's self-indulgent but superbly satisfying Crazy Horse reunion Psychedelic Pill grinds to a halt. Whereas last year's orchestral opus Storytone was overly polished, burying a handful of heartfelt songs beneath layers of syrupy gloop, The Monsanto Years isn't really produced at all. Frequently, the album's seemingly put together with such haste that the tunes seem half-finished at best; at times - the excessively loose "Rules of Change", the yearning but tentative balladry of "Wolf Moon" - both Young and the band seem unsure where their next chord's coming from.

Even when the tunes are more fully fleshed out, the unrefined lyrics are a letdown. "New Day for Love" (the Nelson brothers' harmonies are almost spookily reminiscent of Young's original Crazy Horse sidekick Danny Whitten) and "Big Box", propelled by a vintage latter-day minor key Young riff in the key of "I'm The Ocean", "Be The Rain" or "Trans Am", sacrifice their energy to relentless repetition and clunky couplets that risk becoming an unwitting parody of overly factual finger-pointing school of protest songwriting. These two seem unsure of which wrongs to address, opting instead to have a pop at a number of targets. "Rock Starbucks" - a catchy whistling hook - and the title track, equipped with a lilting melody and gentle groove that never fully ignite, describe their solitary topics with exhausting levels of prosaic detail that makes the proceedings closer in tone to critical pamphlets than enduring songwriting.

That's a shame. Behind the sloppy presentation and self-sabotaging refusal to edit or entertain second thoughts lurk genuinely important points about excessive corporate greed and its impact on consumer choice and human rights. The Monsanto Years has been pitched as an anti-GMO record, but that's only a small part of Young's case against all-powerful corporations with the muscle to force their will on states, small businesses and individuals. It's a timely message. With a bit more time to turn the ample promise of, say, "People Want To Hear" into a fully realised arrangement with a properly finished set of lyrics, plenty of folks might have been keen to join Young's protest choir. As things stand, The Monsanto Years is another inessential and underpowered Neil Young album to file alongside the likes of 2003's ecological garage rock opera Greendale: good ideas and inspiring ideals grounded by half-baked presentation and paucity of substantial songcraft.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

DITZ

Never Exhale

Maribou State

Hallucinating Love

Anna B Savage

You and i are Earth