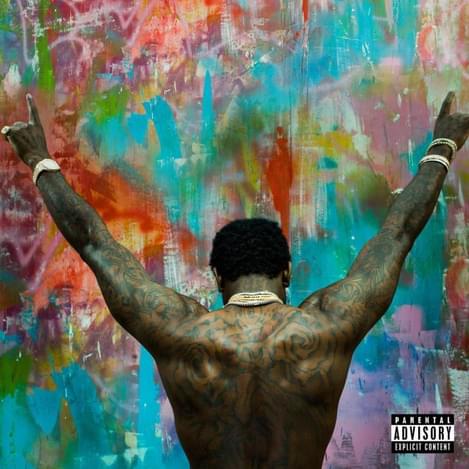

Gucci Mane balances history and legacy building with measurable progress on his post-prison debut

"Everybody Looking"

Over the past decade, Gucci Mane’s infamous propensity for trouble has been matched only by his propensity towards near unparalleled levels of productivity. And while mainstream critics were gradually coming to terms with the sheer scope of Gucci’s influence, his destructive habits only seemed to be spiraling further out of control. It was a ripe recipe for myth-making. And the myth mushroomed when, in 2013, a series of assault charges - on top of other things - eventually landed him a three-year jail sentence. Now he’s out, he’s three years sober, and it’s clear that Gucci’s working consciously to allow something of a clearer picture to come into focus. There’s even shades of remorse. On "1st Day Out Tha Feds" Gucci addresses his myth and myriad pitfalls on brutally honest terms: “A lot of people scared of me and I can’t blame them/They call me crazy so much I think I’m starting to believe them/I did some things to some people that was downright evil/Is it karma coming back to me, so much drama/Own momma turned her back on me, and that’s my momma.” He’s refined the density of his delivery and seems to be holding back on his arsenal of flows, so this time listeners don’t miss a word. He’s got a lot to get off his chest. And with the help of friends and long time collaborators Zaytoven and Mike WiLL made-it overseeing production, it makes for a powerful mission statement.

But these reforms and edits have come at the expense of the sheer range of ideas and concepts that makes listening to an older, stoned (and admittedly more tormented) Gucci Mane so bizarre and exhilarating. There was an erratic, de-centred, schizophrenic quality to Gucci’s writing in the past. He’d slur, chew syllables, gobble words, speed up, slow down, spit them back out. He had about a million different ways to describe cars and jewelry; would obsess over a single idea or theme or object and run wild with it: obscure reference points, flashes of images, vivid non-sequiturs, colours (“Benz look like fruity loops/Diamonds look like juicy fruit/See-through golden brownish coupe/Same colour as apple juice”), even scale seemed a source of endless fascination for Gucci (“humungous, enormous, Gucci riding Jurassic/26 inches beating hard in traffic”.) In comparsion, Everybody Looking is firmly anchored in something like reality, and the writing plays out as such in conventional, concrete steps, with an understandable degree of urgency. The form is terse and the concepts are shrunk to a digestible size, aiming to remain in one completed piece as they volley into our atmosphere. Which certainly makes the bulk of Everybody Looking less overtly imaginative than Gucci’s formerly frantic and congested raps - and probably less vulnerable. But with less shrapnel to dodge and less ill pairings to unpick it might at least help more conservative or literal-minded listeners appreciate Gucci’s (if anyone was still in doubt) demonstrable ability to put words in some semblance of order, and make them rhyme.

This is safe territory for Gucci. By indulging in structure and in hooks, he’s doing what he does best – and better than most. He finds a mantra and hammers it home for three or four furious minutes until it’s burned into the back of your eyelids. On "Robbed" he reminisces obsessively about the fact that yes he did get robbed, and no he’s not ashamed to admit it. On "All My Children" - which contains a typically syrupy Gucci Mane hook, dribbling over thick shuddering base - he takes the opportunity to reaffirm his reputation and status as both a successful discoverer of talent (Gucci is responsible for giving Young Thug his big break) and undeniable originator of styles, aesthetics, sounds, ideas. It’s also a cool toast to those who’ve inherited this legacy (“I had to make a track to say I’m proud of you/Stop the track to tell my children that I’m proud of them”), which is nicely balanced with a humbling nod to his very own predecessors: “But how a drug dealer from East Atlanta go platinum?/Master P, ’93, mixed with a lil Eazy-E.” On "Richest N**** In The Room", Gucci repackages a well-worn autobiographical tale with greater finesse and stronger intent, but with few fresh insights to truly excite. A lot of Everybody Looking falls into this grey area. What it evidently lacks in ideas and concepts, it makes up for in well-channeled cathartic energy.

If Gucci’s making an effort to get grounded - balancing history and legacy-building, with progress and relevancy - then it’s plainly helped by the fact that his two chief engineers, Mike WiLL and Zaytoven, have provided him with a sonic platform that’s emphatic and fierce, but stripped back and undistracted. Sonically, there’s little confusion here. Gucci’s able to rap firmly on top of the beats, rather than through them, or just behind them. "Pussy Print" is all deep space and eerie minimalism (it also gives us some of Gucci’s stranger moments on the tape: “There’s an elephant in the room/Guess who’s the motherfuckin elephant?...(it’s Gucci).”) And the production on the album’s centerpiece, "Guwop Home", allows Young Thug’s inimitable elasticity to take centre stage, unfurling and snapping back across a set of distinctive staccato piano keys. "Pop Music" takes a slightly different turn, with an insane wall of industrial noise that’ll make your brain rattle against the walls of your skull.

Gucci Mane knows you can’t dwell in the past, and Everybody Looking is at least trying to Look Forward. To the Guwop purist, even outside the understandable rustiness of his raps, Everybody Looking will sound somewhat limited with regards to its sense of scope or ambition, preferring instead to stay anchored firmly at eye-level. It’s not hard to see why, though. Post-prison, a degree of stability, focus and self-control seems important to Gucci. He looks better, sounds happier and has immediately embedded himself within a thriving circle of creative energies - old friends, new tastemakers and emerging talents. It’s given him the recourse to turn his enormous skyward gaze in on himself. It might not be totally illuminating, but it’s at least an indication that Gucci wants us to see a different sort of picture - a portrait of an artist and a man, rather than a chaotic blurring of the two.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Great Grandpa

Patience, Moonbeam

Deafheaven

Lonely People With Power

Perfume Genius

Glory