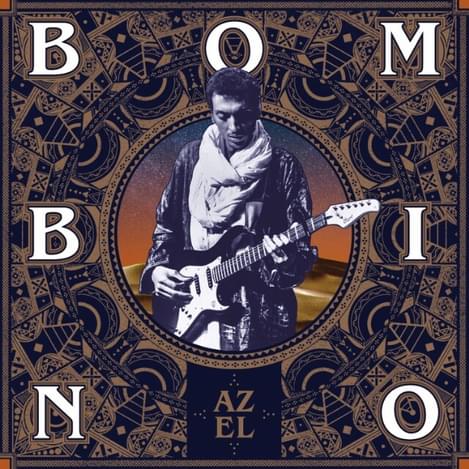

Rock and rebellion march hand in hand on Bombino's Azel

"Azel"

But as Schwartz’ powerful film shows, this crossover of music cultures is not simply a pleasing result of our hyper-globalised society, but because these North Africans have a solemn story to tell.

For decades a heady cocktail of political rebellions, uranium and land disputes, and Jihadist uprisings have forced many to flee their homes and find exile in neighbouring lands and deserts. In 2007 after the execution of two prominent Tuareg musicians, Omara Moctar, a talented young guitarist, fled his native Agadez, Niger with friends and family and sought refuge in Burkina Fasso. Moctar had earned the nickname Bombino whilst playing temporarily with the revered Tuareg guitarist Haja Bebe, and it was under this name that the ‘little one’ would prick ears worldwide.

Bombino’s time in exile was the subject of Agadez, the Music and the Rebellion, a 2010 documentary by filmmaker Ron Wyman, who would help bring the artist into the limelight; a year later Bombino had released his first-full length, Agadez, which would top the iTunes World Chart and inspire The Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach to work with Bombino for his 2013 follow up, Nomad.

Fully instated into the Western popular music market and touring circuits, for Bombino’s third instalment, Azel, the Nigerien returned to the States to record with Dirty Projectors’ Dave Longstreth at the Applehead Studios in Woodstock, New York. Describing the recording process, Bombino has said that Longstreth had a more open-floored approach than Auerbach’s more directorial style, which made for a fruitful working relationship: "To work with Tuareg music and musicians can be very complicated. We are not like American musicians in many ways. Our skills and our knowledge are very different from Western musicians […] So this can be a big challenge, but Dave handled himself very gracefully".

As The Guardian’s Ally Carnwath hints at, however, perhaps there is an opportunity lost in Longstreth’s laissez-faire method; indeed, the record remains very much one sided and the sound characteristically Bombino. But importantly, Azel is not meant as a collaborative project but a continuation of the Tuareg legacy. For nomadic people, identity is a slippery term and one that cannot be so easily assigned by the markers we use for settled societies. More emphasis is thus placed on cultural expressions, and given the revolutionary and rebellious nature of the Tuareg’s project, coherency and tradition are not important but necessary. As he sings in album opener “Akhar Zaman (This Moment)”: [translated] ‘Our ancestral language and alphabet are threatening to disappear and our dearest practices are losing their place’.

In any case, from first listen of the record, it comes of little surprise why Longstreth might be attracted to Moctar’s music, with his tireless guitar licks that seem to ooze narrative at every turn. Longstreth’s ear is a pertinent one for Bombino too; the production emphasises the depth of the spirited bass-lines whilst also capturing the guitars with high-end clarity.

Indeed, the guitars have a sort of transcendental importance for the musician. The image of the guitar as a counter-symbol to that of the gun has its roots in the Vietnam war protest songs of the late '60s, although importantly for Jimi Hendrix the guitar was not a tool of peace but rather an axe, as in “Machine Gun”. Hendrix was a huge influence on Bombino as he cultivated his playing as a teen whilst in Algeria, and that’s certainly still evident in Azel; from start to finish Moctar’s left hand flutters and glides to mesmerising and melodious effect, either electronically as in “Iwaranagh (We Must)” or acoustically in tracks like “Igmayagh Dum (My Lover)”.

Interestingly, there’s a splash of reggae thrown into the mix at some points, or as Bombino calls it, ‘Tuareggae’. It fits surprisingly well, as in “Timtar (Memories)”, a delightful track with call and response and tempo changes, and which is aptly named given it’s strangely nostalgic feel.

Importantly though, for Bombino and his fellow Tuareg, to pick up a guitar and play so enticingly and vibrantly is a direct act of rebellion, at least in the context of their home countries. After the 2007 Tuareg rebellion, the Nigerien government banned the use of guitars, clearly not underestimating their power for spreading revolt. This considered, Azel becomes even more triumphant, and listening to it all the more enjoyable; whilst he sings in Tamasheq, the language of the Tuareg, his guitar truly has a voice of its own.

Since its genesis, rock music — in a Western context, anyway — has been subject to criticisms surrounding the authenticity of its seemingly rebellious aesthetic. As Keir Keightley shows in his insightful essay ‘Reconsidering Rock’, even at its most outspoken moments, rock has only existed within the framework of a mass-entertainment industry. While Bombino and his fellow Tuareg's music is now well settled in the same market, the rebellion which fuels their music is very real, and as such, Azel is a breath of fresh air.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday