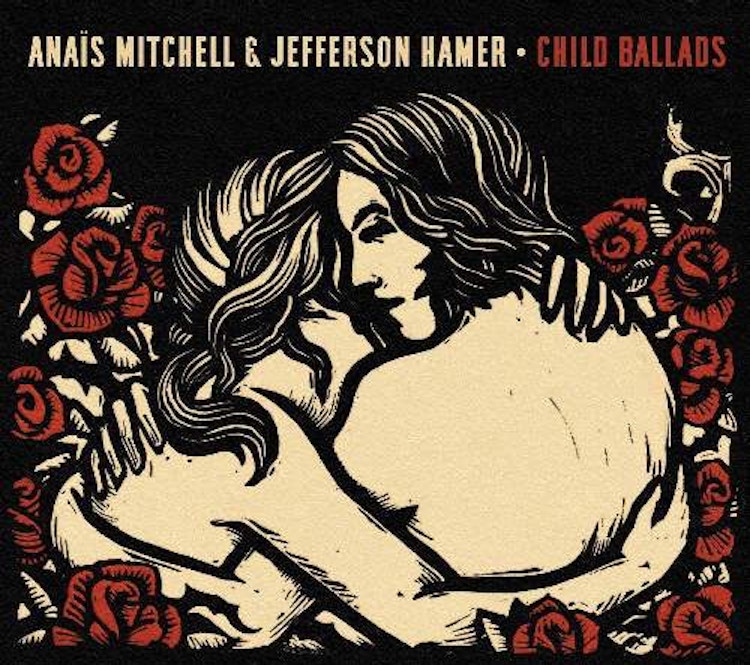

Anaïs Mitchell and Jefferson Hamer – Child Ballads

"Child Ballads"

Francis James Child was an intrepid chap: Harvard University’s first Professor of English, he ventured to Britain to collect folk songs in the late nineteenth century and published his miscellany in five volumes. While some traditional singers are still very close to their sources, song collecting might seem a curious endeavour these days – and the image of scholars detailing with diligence the songs of the common man is easy to regard with a gently gibing jocularity. Nevertheless, the Child ballads have become a compelling resource for songsmiths of all descriptions.

Anaïs Mitchell and Jefferson Hamer are the latest Americans to borrow our ballads, and it’s a move that makes excellent sense. While Hamer’s association is more immediate – the seasoned folk collaborator recorded another Child ballad on last year’s traditional album The Murphy Beds – Mitchell’s best work has also been rich with traditional motifs. Young Man in America‘s ‘Tailor’ earned a nomination at this year’s BBC Folk Awards; while the bowing trees of ‘Wedding Song‘ (a Hadestown cut performed on the Child Ballads tour) echo ‘The Cherry-Tree Carol’ (Child 54). When Mitchell brought her folk-opera to London in 2011, Jim Moray played Orpheus and Martin Carthy the god of the underworld.

Child Ballads is a beautiful album, and the duo’s mission to make their own mark on these songs is accomplished with delicate aplomb. Set sparingly to two guitars and little more (deciding against folk rock arrangements was probably wise), these versions are nevertheless modernised Americanised takes on traditional tales from British social singing. Subplots are dropped and characters cut: shorn of its elfin queen and threatened tithe to hell, ‘Tam Lin’ has never sounded more tranquil. Even so, Mitchell conveys its heroine’s story with the most human emotion of the seven songs, and Scottish folk’s most famous power ballad survives its abridged folklore to become the pick of the album.

Anaïs Mitchell’s sweetening voice remains her most distinctive trait as a performer, and Hamer’s less striking vocals complement this acquired taste well, cushioning her high pitch. At times, dialogue is sung almost too tenderly – the king’s capricious proclamations in ‘Willy of Winsbury’ are a little lacklustre, while the witless witch’s raging disclosure of her spells in ‘Willie’s Lady’ are more info dump than tantrum. Nevertheless, their gentle blend makes charming music, and they know each other’s strengths: plans for this album have been gestating for at least the last two years.

With 305 distinct ballads to choose from, selecting only seven must have called for much whittling. ‘Clyde Waters’ and ‘Geordie’ were chosen by mutual appreciation of older recordings, by Nic Jones and Martin Carthy respectively. Elsewhere we might infer a fondness for pregnant protagonists and titular Willies. The commonest thread, however, is change and danger: in spells and sex and shipwrecks, in tangled morality and bold devotion.

Vaughan Williams is quoted as declaring “The practice of re-writing a folk song is abominable, and I wouldn’t trust anyone to do it except myself”, but with multiple variants in existence by Child’s time, interpretation is as old the songs. The fifteenth century ‘Riddles Wisely Expounded’ (Child 1) repeats the second and fourth lines as a chorus, and it’s a jolly good thing that Mitchell and Hamer replace the original “Fa la la la, fa la la la ra re” with “And you’ll beguile a lady soon”. (Incidentally, setting an exam for your lover seems an obtuse way to beguile – but it does the trick here…)

While the duo steer well clear of the pitfall of patronising these songs as quaint antiques to be esteemed and preserved, they can feel slightly constrained by the beauty bestowed. All are swathed in pretty grace that is snugger than perhaps it should be, the album a warm blanket when it might have been a winter’s night.

The great gift of these ballads is the broad scope of interpretation they inspire and sustain, in some cases centuries after they were first sung. This is an album that emphasises the songs’ aesthetic appeal above all (eschewing liner notes for accompanying illustrations). Mitchell and Hamer are skilled songwriters and rise to the challenge of restyling these exotic British myths in their own image. It is a cohesive collection, each ballad given similar treatment, steadied and prettied to similar effect, and the exercise is sadly brief. A big debt is owed to twentieth century icons; the concessions made to their twenty-first century audience are small enough. This, and the winsome way it is accomplished, makes Child Ballads well worthy of its source.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

Kendrick Lamar

GNX

Father John Misty

Mahashmashana

Kim Deal

Nobody Loves You More